Volume 24, Number 9—September 2018

Research Letter

Dirofilaria repens Nematode Infection with Microfilaremia in Traveler Returning to Belgium from Senegal

Abstract

We report human infection with a Dirofilaria repens nematode likely acquired in Senegal. An adult worm was extracted from the right conjunctiva of the case-patient, and blood microfilariae were detected, which led to an initial misdiagnosis of loiasis. We also observed the complete life cycle of a D. repens nematode in this patient.

On October 14, 2016, a 76-year-old man from Belgium was referred to the travel clinic at the Institute of Tropical Medicine (Antwerp, Belgium) because of suspected loiasis after a worm had been extracted from his right conjunctiva in another hospital. Apart from stable, treated arterial hypertension and non–insulin-dependent diabetes, he had no remarkable medical history. For the past 10 years, the patient spent several months per year in a small beach house in Casamance, Senegal, and did not travel to any other destination outside Belgium. His last stay in Senegal was during October 2015–May 2016, during which time he took care of dogs roaming on the beach.

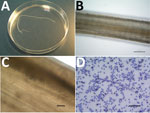

On September 30, 2016, unilateral right conjunctivitis developed in the patient, and he was referred to an ophthalmologist, who extracted a worm (length 10 cm, diameter 470 μm) (Figure, panel A). The patient did not report any previous symptoms such as itching, larva migrans, or migratory swelling.

Results of a physical examination were unremarkable. Blood analysis showed a leukocyte count of 8,330 cells/μL and 16.8% eosinophils. All other first-line laboratory parameters, including total level of IgE, were within reference ranges. A pan filaria IgG-detecting assay (Acanthocheilonema viteae ELISA Kit; Bordier Affinity Products SA, Crissier, Switzerland) showed a positive result. All other relevant serologic assays showed negative results. Blood smear examination after Knot concentration showed 6 microfilariae of Dirofilaria sp./mL of blood.

Although treatment for such infections is not well established, the patient was given ivermectin (200 μg/kg, single dose) on October 15. The patient had general itching and fever (temperature up to 40°C) the next day. Blood test results on October 26 showed a leukocyte count of 8,410 cells/μL and 27.9% eosinophils. The patient recovered uneventfully. In September 2017, the patient was free of symptoms, and his eosinophil count was 470 cells/μL.

Human dirofilariasis is a mosquitoborne zoonosis caused by filarial worms of the genus Dirofilaria, which has 2 subgenera: Dirofilaria (the most common species is D. immitis) and Nochtiella (the most common species is D. repens). The main clinical manifestations are subcutaneous or ocular nodules, and a diagnosis is usually made by biopsy or worm extraction. The risk for humans to acquire dirofilariasis has increased because of climate changes and larger distribution ranges of vectors (1).

Human dirofilariasis is currently considered an emerging zoonosis (2). D. repens nematodes have a large geographic distribution that includes Africa, Asia, and Europe and have recently spread into colder regions (3). Studies of primates indicate that D. repens nematodes need to develop for ≈25–34 weeks before they are fully mature and produce microfilariae (4). This finding suggests that the patient we report acquired the infection in Senegal, possibly through close contact with dogs.

Initially, loiasis was suspected as a diagnosis, given the location of the adult worm and presence of microfilaremia. However, the length (10 cm) of the adult worm did not correspond to a Loa loa worm, which can reach a maximum length of ≈7 cm. Microscopic examination of the cuticle identified conspicuous longitudinal ridges, which are typical for certain Dirofilaria spp. but absent in L. loa worms (Figure, panel B). These ridges also ruled out D. immitis worms.

When we took the largest diameter of the adult worm (470 μm) into account, we made a diagnosis of D. repens nematode infection (5). Eggs found in utero (Figure, panel C) confirmed that the worm was a gravid adult female. This diagnosis was supported by morphologic features of the blood microfilariae: terminal extremities that did not contain nuclei (L. loa microfilariae have nuclei extending to the tip of the tail) and short cephalic spaces containing 2–4 nuclei (Figure, panel D; Technical Appendix Figure). We measured 25 larvae, and they had an average length of 376 μm (range 357–395 μm) and an average diameter of 9.7 μm (range 7.5–10.0 μm), all features compatible with D. repens microfilariae (6,7).

We attempted to provide molecular confirmation of the infecting species by using 2 PCRs: 1 reported by Gioia et al. in 2010 (8) and 1 reported by Latrofa et al. in 2012 (9). Both techniques, which were performed with material from the adult worm, did not confirm identification of infecting species, probably because of prolonged preservation of the worm in formaldehyde.

D. repens worms seldom fully develop and produce microfilariae in humans. To our knowledge, 5 such cases have been reported: 3 with microfilariae in tissues surrounding adult worms and 2 with microfilariae in blood (10). There might have been immune impairment in our patient with diabetes, which enabled completion of the worm cycle, a phenomenon also observed in macaques with decreased immunity (4).

In conclusion, this case highlights the need for careful parasitologic examination when clinical and laboratory findings (i.e., presence of an eye worm and microfilaremia) lead to a diagnosis that is epidemiologically unexpected. In addition, clinicians should be aware that similar clinical presentations might also be increasingly observed in nontropical settings.

Mr. Potters is a skills laboratory teacher and a medical laboratory technologist at the national reference laboratory for parasitology at the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium. His research interest is tropical parasitology.

Acknowledgment

We thank all laboratory staff involved in the study for providing technical assistance and Pierre Dorny, Renaud Piarroux, and Anne-Cécile Normand for providing assistance with the molecular techniques.

References

- Diaz JH. Increasing risks of human dirofilariasis in travelers. J Travel Med. 2015;22:116–23. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pampiglione S, Rivasi F, Angeli G, Boldorini R, Incensati RM, Pastormerlo M, et al. Dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria repens in Italy, an emergent zoonosis: report of 60 new cases. Histopathology. 2001;38:344–54. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pietikäinen R, Nordling S, Jokiranta S, Saari S, Heikkinen P, Gardiner C, et al. Dirofilaria repens transmission in southeastern Finland. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:561. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wong MM. Experimental dirofilariasis in macaques. II. Susceptibility and host responses to Dirofilaria repens of dogs and cats. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1976;25:88–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- MacDougall LT, Magoon CC, Fritsche TR. Dirofilaria repens manifesting as a breast nodule. Diagnostic problems and epidemiologic considerations. Am J Clin Pathol. 1992;97:625–30. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Magnis J, Lorentz S, Guardone L, Grimm F, Magi M, Naucke TJ, et al. Morphometric analyses of canine blood microfilariae isolated by the Knott’s test enables Dirofilaria immitis and D. repens species-specific and Acanthocheilonema (syn. Dipetalonema) genus-specific diagnosis. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:48. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Liotta JL, Sandhu GK, Rishniw M, Bowman DD. Differentiation of the microfilariae of Dirofilaria immitis and Dirofilaria repens in stained blood films. J Parasitol. 2013;99:421–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gioia G, Lecová L, Genchi M, Ferri E, Genchi C, Mortarino M. Highly sensitive multiplex PCR for simultaneous detection and discrimination of Dirofilaria immitis and Dirofilaria repens in canine peripheral blood. Vet Parasitol. 2010;172:160–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Latrofa MS, Weigl S, Dantas-Torres F, Annoscia G, Traversa D, Brianti E, et al. A multiplex PCR for the simultaneous detection of species of filarioids infesting dogs. Acta Trop. 2012;122:150–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fontanelli Sulekova L, Gabrielli S, De Angelis M, Milardi GL, Magnani C, Di Marco B, et al. Dirofilaria repens microfilariae from a human node fine-needle aspirate: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:248. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: July 31, 2018

Table of Contents – Volume 24, Number 9—September 2018

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Idzi Potters, Department of Clinical Sciences, Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp, Kronenburgstraat 43/3, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium

Top