Volume 17, Number 7—July 2011

Dispatch

Plasmodium vivax Malaria among Military Personnel, French Guiana, 1998–2008

Abstract

We obtained health surveillance epidemiologic data on malaria among French military personnel deployed to French Guiana during 1998–2008. Incidence of Plasmodium vivax malaria increased and that of P. falciparum remained stable. This new epidemiologic situation has led to modification of malaria treatment for deployed military personnel.

French Guiana is a French Province located on the northern coast of South America that had 221,500 inhabitants in 2008 (1). Malaria is endemo-epidemic to the Amazon basin. Since 2000, the annual number of Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax malaria cases in French Guiana has ranged from 3,500 to 4,500 (2). Approximately 3,000 French military personnel are deployed annually in French Guiana, and malaria occasionally affects their operational capabilities.

Only military personnel on duty in the Amazon basin are required to take malaria chemoprophylaxis; personnel deployed in coast regions are not. Until February 2001, the chemoprophylaxis regimen consisted of chloroquine (100 mg/d) and proguanil (200 mg/d). During March 2001–October 2003, mefloquine (250 mg/wk) was used. Since November, 2003 malaria chemoprophylaxis has been doxycycline (100 mg/d), which is initiated on arrival in the Amazon basin. All chemoprophylaxis is continued until 4 weeks after departure. Because of the absence of marketing authorization as chemoprophylaxis by the French Medicines Agency, primaquine was not used until recently. Other individual and collective protective measures did not change during 1998–2008.

Despite the availability of chemoprophylaxis, since 2003, several malaria outbreaks have been identified after operations against illegal mining in the Amazon basin (3,4). The purpose of those studies was to describe outbreaks and determine factors related to malaria cases. We report French military health surveillance epidemiologic data on malaria among military personnel deployed to French Guiana during 1998–2008.

Epidemiologic malaria surveillance in French Armed Forces consists of continuous and systematic collection, analysis, interpretation, and feedback of epidemiologic data from all military physicians (Technical Appendix). Malaria is defined as any pathologic event or symptom associated with confirmed parasitologic evidence (Plasmodium spp. on a blood smear, a positive quantitative buffy coat malaria diagnosis test result, or a positive malaria rapid diagnosis test result) contracted in French Guiana. A case occurring in a person during or after a stay in French Guiana without a subsequent stay in another malaria-endemic area was assumed to be contracted in French Guiana. Each malaria attack was considered a separate case. Equal information was available for the entire 11-year study period. Data from weekly reports and malaria-specific forms were used for analysis.

Indicators are expressed as annual incidence and annual incidence rate. The denominator of the annual incidence rate is the average number of military personnel at risk for malaria during a given year.

Statistical analysis was performed by using Epi Info 6.04dfr (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA). Comparisons over time were made by using the χ2 test for trend and between groups by using the Kruskal-Wallis test. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

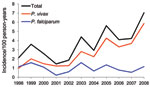

The incidence rate for malaria cases among French military personnel deployed to French Guiana has increased since 1998 (p<0.001). P. falciparum incidence has remained stable (p = 0.10), and P. vivax incidence has increased (p<0.001) (Figure). In 2007 and 2008, French military personnel in French Guiana represented only 23.0% and 22.2% of those deployed to malaria-endemic regions. However, most reported malaria cases were contracted in this region (50.0% and 62.9%, respectively, of all cases). P. vivax was responsible for most malaria attacks reported in French Guiana (Table). The proportion of malaria attacks caused by P. vivax increased from 44% to 84% (p<0.001) during the study period.

In 2008, among the 264 reported cases, 221 were temporarily unavailable for duty. Median lost work days were lower for attacks of P. vivax malaria than for P. falciparum malaria (5 days/attack, interquartile range 4–7 days/attack vs. 7 days/attack, interquartile range 5–10 days/attack; p = 0.006)

Among 264 malaria cases contracted in French Guiana, 39.4% were in persons who had reported >1 malaria attack in the previous 6 months. Among the 221 P. vivax malaria cases, 45.5% were in persons who had already reported >1 P. vivax malaria attack in the previous 6 months. In 2008, among those required to take chemoprophylaxis (i.e., during a mission to the Amazon basin and 28 days after the mission), 45.0% admitted not taking their chemoprophylaxis within 8 days before onset of symptoms.

P. vivax malaria attacks have resulted in a substantial number of lost work days and have adversely affected operational readiness of military personnel. Despite availability of appropriate chemoprophylaxis, since 1998, French Armed Forces have been affected by an increase in incidence of P. vivax malaria. Several causes of this increase have been hypothesized.

First, epidemiologic trends for all-cause malaria in French Guiana and overall reported malaria incidence has not changed substantially since the end of the 20th century: ≈4 000 cases were reported annually during the 1990s (5) and 3,500–4,500 were reported during 2008 (2). However, the proportion of P. vivax malaria has increased from 20% of cases in the 1990s (6) to 56.1% during September 2003–February 2004 among patients at the Cayenne Public Hospital (7). Furthermore, 70% of malaria cases diagnosed in 2006 among French travelers returning from French Guiana were caused by P. vivax (8). One explanation for this parasitologic evolution may involve immigration from Brazil and Suriname to illegal gold-mining areas in the Amazon basin of French Guiana (2,6). These immigrating populations brought P. vivax from high-prevalence regions to an area where an efficient vector for malaria, Anopheles darlingi mosquitoes, was present (9). Changes in weather patterns and regional infrastructure could also explain this increase.

Second, military missions have intensified. In 2008, a police and military operation to reduce illegal gold-panning activities in the Amazon basin occurred in French Guiana. This operation might explain the 2008 peak in the incidence rate. Since 2002, these operations have resulted in several outbreaks among forces in French Guiana, especially in 2003 and 2005 (2,3).

Third, deficiencies have occurred in implementing individual and collective protective measures. These military operations were conducted by personnel from French Guiana or France, few had any rainforest experience. Despite extensive training, instructions were clearly not followed, as demonstrated by a 45% noncompliance rate for chemoprophylaxis.

P. vivax has accounted for >80% of reported malaria cases in French Guiana for the past 3 years. In addition, relapses of P. vivax malaria occur in the absence of radical treatment. In 2008, 45.5% of persons with P. vivax malaria had already reported >1 P. vivax malaria attack in the past 6 months. Although the P. vivax malaria mortality rate is low, the effect of P. vivax malaria on force operational readiness is high because relapses decrease the availability of military personnel. In addition, P. vivax malaria can be severe, despite its reputation as a mild form of malaria (10). Since 2009, to reduce the number of relapses, a French Ministry of Defense circular has recommended treatment with primaquine for 2 or 3 weeks after a first attack of P. vivax malaria. Studies of the use of primaquine chemoprophylaxis are ongoing (11–13).

In conclusion, the incidence of P. vivax malaria is increasing in French Guiana, especially in French Armed Forces. The incidence of P. falciparum malaria remains stable. This new epidemiologic finding can affect the level of individual health and operational capabilities. Performance of vector evaluation studies and control in the regions could be another possible intervention.

Dr Queyriaux is a physician at the Institut de Médicine Tropicale du Service de Santé des Armées, Marseille, France. His research interests are public health and epidemiology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Dearden for assistance with the preparation of this report.

This study was supported by the French Medical Forces.

References

- Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques. Population des régions au 1 Janvier [cited 2009 Nov 23]. http://www.insee.fr/fr/themes/tableau.asp.

- Carme B, Ardillon V, Girod R, Grenier C, Joubert M, Djossou F, Update on the epidemiology of malaria in French Guiana [in French]. Med Trop (Mars). 2009;69:19–25.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Michel R, Ollivier L, Meynard JB, Guette C, Migliani R, Boutin JP. Outbreak of malaria among policemen in French Guiana. Mil Med. 2007;172:977–81.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Verret C, Cabianca B, Haus-Cheymol R, Lafille JJ, Loran-Haranqui G, Spiegel A. Malaria outbreak in troops returning from French Guiana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1794–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Juminer B, Robin Y, Pajot FX, Eutrope R. Malaria pattern in French Guiana [in French]. Med Trop (Mars). 1981;41:135–46.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cochet P, Deparis X, Morillon M, Louis FJ. Malaria in French Guiana: between tradition and modernism [in French]. Med Trop (Mars). 1996;56:185–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- de Lavaissiere M, d’Ortenzio E, Dussart P, Fontanella JM, Djossou F, Carme B, Febrile illness at the emergency department of Cayenne Hospital, French Guiana. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:1055–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Behrens RH, Carroll B, Beran J, Bouchaud O, Hellgren U, Hatz C, The low and declining risk of malaria in travellers to Latin America: is there still an indication for chemoprophylaxis? Malar J. 2007;6:114. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Girod R, Gaborit P, Carinci R, Issaly J, Fouque F. Anopheles darlingi bionomics and transmission of Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium malariae in Amerindian villages of the Upper-Maroni Amazonian forest, French Guiana. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103:702–10. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Picot S. Is Plasmodium vivax still a paradigm for uncomplicated malaria? [in French]. Med Mal Infect. 2006;36:406–13. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Oliver M, Simon F, de Monbrison F, Beavogui AH, Pradines B, Ragot C, New use of primaquine for malaria [in French]. Med Mal Infect. 2008;38:169–79. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Soto J, Toledo J, Rodriquez M, Sanchez J, Herrera R, Padilla J, Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled assessment of chloroquine/primaquine prophylaxis for malaria in nonimmune Colombian soldiers. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:199–201. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Soto J, Toledo J, Rodriquez M, Sanchez J, Herrera R, Padilla J, Primaquine prophylaxis against malaria in nonimmune Colombian soldiers: efficacy and toxicity. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:241–4.PubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Table

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 17, Number 7—July 2011

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Benjamin Queyriaux, Département d’Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique, Institut de Médicine Tropicale du Service de Santé des Armées, Parc du Pharo, Boulevard Charles Livon, Marseille 13007, France

Top