Pulmonary Paragonimiasis in Native Community, Esmeraldas Province, Ecuador, 2022

Volume 28, Number 10—October 2022

José C.N. Diaz, Mariella Anselmi, Manuel Calvopiña, Mayra E.P. Vera, Yuvy L.C. Cabrera, Javier J. Perlaza, Luz A.O. Cabezas, Christian O.R. Gaspar, and Dora Buonfrate

Author affiliations: Distrito de Salud 08D05 San Lorenzo, San Lorenzo, Ecuador (J.C.N. Diaz, Y.L.C. Cabrera, J.J. Perlaza, L.A.O. Cabezas, C.O.R. Gaspar); Centro de Epidemiologia Comunitaria y Medicina Tropical, Esmeraldas, Ecuador (M. Anselmi); Universidad de las Americas, Quito, Ecuador (M. Calvopiña); Energy e Palma Energypalma SA, Montecristi, Ecuador (M.E.P. Vera); Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico IRCCS Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital, Negrar, Verona, Italy (D. Buonfrate)

Suggested citation for this article

Abstract

Paragonimiasis is a food-borne infection caused by several species of the Paragonimus fluke. Clinical manifestations can mimic tuberculosis and contribute to diagnostic delay. We report a cluster of paragonimiasis in a community in Ecuador, where active surveillance was set up after detection of the first 2 cases.

Human paragonimiasis is a foodborne disease caused by trematode worms of the genus Paragonimus (1). Several species that have different geographic distributions have been associated with human infection (2). Paragonimiasis is caused by ingestion of raw/undercooked freshwater crabs or crayfish infested by metacercariae of Paragonimus species. Thus, it is frequently reported in Asia because of cultural dietary customs (1,3). Clusters are occasionally reported in Africa (4) and the Americas, where cases are observed mostly in countries in Latin America (5). Localized infection with P. kellicotti trematode occurs in the United States (1,5).

In Ecuador, cases have been reported from almost all provinces, but lack of official recording by the Ministry of Health and few active surveillance surveys probably cause an underestimation of the incidence (5). Nevertheless, Ecuador is considered the country with the highest incidence of paragonimiasis in South America (5). The main trematode species known to cause paragonimiasis in Ecuador is P. mexicanus, although molecular characterization has not been performed extensively. Thus, information about circulating species might be incomplete (5,6).

Symptoms include fever and respiratory involvement, and most persons have a productive cough with rusty sputum or chest pain that can last from a few months to years. Thus, tuberculosis is the main condition to be ruled out in differential diagnosis (6,7). We report a public health intervention for a cluster of paragonimiasis observed during the end of 2021‒May 2022, in San Lorenzo, Ecuador.

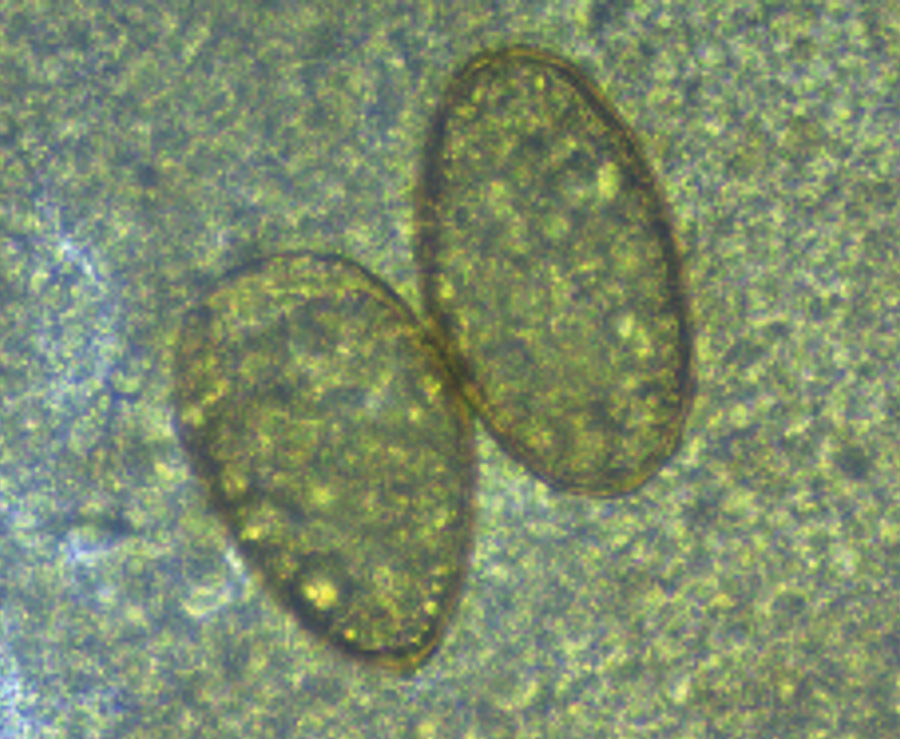

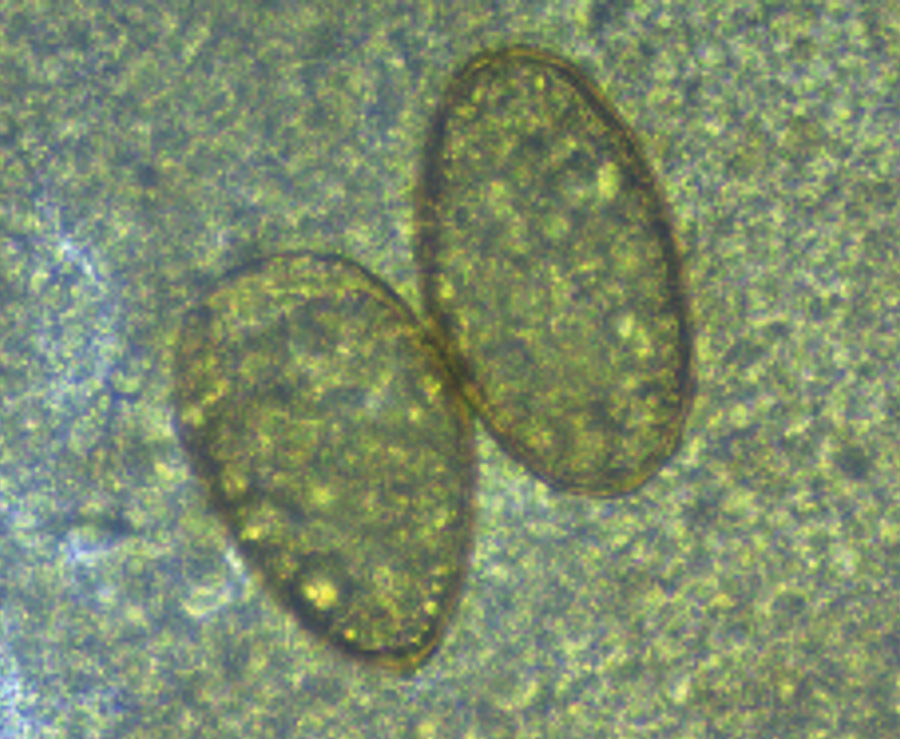

The first 2 cases were diagnosed in laborers working on the same palm oil farm. They both reported productive cough with rusty sputum and dyspnea lasting for about 4 months (first case-patient) and for at least 4 years (second case-patient). The second patient had been tested several times for tuberculosis but was not previously tested for other causes of respiratory symptoms. Microscopic examination of acid-fast‒stained smears of sputum ruled out tuberculosis, but directly observed microscopic examination showed parasite eggs (Figure). Specimens were then sent to the Laboratory of Parasitology of the Universidad de las Americas in Quito, where diagnosis of paragonimiasis was made. Both patients confirmed the habit of eating raw freshwater crustaceans.

After the first 2 cases, the Department of Epidemiology of San Lorenzo Health District organized a meeting with the community where the 2 case-patients lived. Aims of the intervention were to ascertain whether the infection was spreading in the community and evaluate possible control strategies. Healthcare workers collected 3 sputum samples from each of 22 persons who had compatible respiratory symptoms and 1 fecal sample from each of 36 asymptomatic persons, including family members of the positive case-patients.

Paragonimus eggs were found in samples from 8 persons, all from the same community (La Ceiba), except for 1 person (who lived in Balsareño but worked on the same palm oil farm as the first case-patient) (Table). Symptoms lasted for months in all persons reporting them.

Praziquantel was donated by the Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico Sacro Cuore Don Calabria to the Centro de Epidemiologia Comunitaria y Medicina Tropical. This drug was administered by the physician at the local health center to infected persons at a dose of 25 mg/kg, 3 times/day for 2 days.

Our study highlights some limitations that hampered estimation of incidence of paragonimiasis in Ecuador. The first limitation is delay in diagnosis. Because knowledge about this parasite is scarce, local physicians seldom prescribe diagnostic tests that could help diagnosis, and misdiagnosis as tuberculosis can be frequent. Limited diagnostic capacity can contribute to the underestimation because the sensitivity of microscopic examination is low, in particular for persons who have mild-to-moderate disease: 30%–40% for a sputum sample and 11%–15% for a stool sample (1). Multiple sampling increases sensitivity (1), but collection of a series of specimens over time can be difficult in remote settings for cultural and logistic issues.

Although stool microscopy has low sensitivity, it can detect Paragonimus eggs in persons who do not have respiratory symptoms. Other diagnostic tests, such as serologic or molecular methods, are not available in Ecuador, and have been seldom used there, for research purposes (5,8). Moreover, serologic assays have been implemented mostly for other species, such as P. westermani and P. kellicotti worms (8,9), and clinical validation for P. mexicanus worms is lacking (9,10). Limited access to healthcare services in some remote communities can further cause late diagnosis.

Control strategies to limit human infection are hampered by the wide presence of the parasite in many domestic and wild mammals, and the complex life cycle involving 2 intermediate hosts (snail and crustacean) (5). Thus, health education on proper food preparation is the main intervention to reduce infections (1).

Dr. Diaz is a physician at the Distrito de Salud 08D05 San Lorenzo in San Lorenzo, Ecuador and coordinator of the epidemiology surveillance service of the San Lorenzo Health District. His primary resesarch interests are epidemiology and hygiene.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alvaro Santiago Guerrero Moscoso, Adela Boboy Porozo, and Joel Adrian Mendoza Alarcon for providing excellent support for screening and management and Teresa Zuppini for organizing drug donation.

This study was partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Health Fondi Ricerca Corrente to Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital, Linea 2.

References

Diaz JH.

Paragonimiasis acquired in the United States: native and nonnative species. Clin Microbiol Rev.

2013;

26:

493–

504.

DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar Blair D.

Lung flukes of the genus Paragonimus: ancient and re-emerging pathogens. Parasitology.

2022;

149:

1286–

95.

DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar Lane MA,

Marcos LA,

Onen NF,

Demertzis LM,

Hayes EV,

Davila SZ,

et al. Paragonimus kellicotti flukes in Missouri, USA. Emerg Infect Dis.

2012;

18:

1263–

7.

DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar Rabone M,

Wiethase J,

Clark PF,

Rollinson D,

Cumberlidge N,

Emery AM.

Endemicity of Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and mapping reveals stability of transmission in endemic foci for a multi-host parasite system. PLoS Negl Trop Dis.

2021;

15:

e0009120.

DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar Calvopiña M,

Romero D,

Castañeda B,

Hashiguchi Y,

Sugiyama H.

Current status of Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in Ecuador. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz.

2014;

109:

849–

55.

DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar Calvopina M,

Romero-Alvarez D,

Macias R,

Sugiyama H.

Severe pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis caused by Paragonimus mexicanus treated as tuberculosis in Ecuador. Am J Trop Med Hyg.

2017;

96:

97–

9.

DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar Lane MA,

Barsanti MC,

Santos CA,

Yeung M,

Lubner SJ,

Weil GJ.

Human paragonimiasis in North America following ingestion of raw crayfish. Clin Infect Dis.

2009;

49:

e55–

61.

DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar Xunhui Z,

Qingming K,

Qunbo T,

Haojie D,

Lesheng Z,

Di L,

et al. DNA detection of Paragonimus westermani: Diagnostic validity of a new assay based on loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) combined with a lateral flow dipstick. Acta Trop.

2019;

200:

105185.

DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar Fischer PU,

Weil GJ.

North American paragonimiasis: epidemiology and diagnostic strategies. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther.

2015;

13:

779–

86.

DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar Procop GW.

North American paragonimiasis (Caused by Paragonimus kellicotti) in the context of global paragonimiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev.

2009;

22:

415–

46.

DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Suggested citation for this article: Diaz JCN, Anselmi M, Calvopiña M, Vera MEP, Cabrera YLC, Perlaza JJ, et al. Pulmonary paragonimiasis in native community, Esmeraldas province, Ecuador, 2022. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022 Oct [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2810.220927

10.3201/eid2810.220927

Figure

Figure. Paragonimus eggs from sputum from a patient in Ecuador. Eggs are yellow, elongated, have a thick shell, and are asymmetric with 1 end slightly flattened. The operculum is clearly visible at the large end and is thickened at the abopercular end. Original magnification ×40, size 80–90 μm × 45–50 μm.

Table

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 10 persons infected with Paragonimus eggs, Ecuador

| Case-patient |

Age, y/sex |

Sample positive for eggs |

Symptoms |

| 1 |

24/M |

Sputum |

Rusty sputum and dyspnea while working, episodes of productive cough |

| 2 |

32/M |

Sputum |

Rusty sputum and mild dyspnea, episodes of productive cough |

| 3 |

27/F |

Stool |

None |

| 4 |

20/M |

Sputum |

Rusty sputum |

| 5 |

29/F |

Stool |

None |

| 6 |

32/M |

Sputum |

Rusty sputum |

| 7 |

8/M |

Stool |

None |

| 8 |

10/M |

Stool |

None |

| 9 |

31/F |

Sputum |

Rusty sputum |

| 10 |

22/F |

Sputum |

Rusty sputum |