Volume 17, Number 9—September 2011

Dispatch

Tubulinosema sp. Microsporidian Myositis in Immunosuppressed Patient

Abstract

The Phylum Microsporidia comprises >1,200 species, only 15 of which are known to infect humans, including the genera Trachipleistophora, Pleistophora, and Brachiola. We report an infection by Tubulinosema sp. in an immunosuppressed patient.

Initially designated as primitive eukaryotic protozoa, the microsporidia are now classified as fungi (1,2) with >1,200 known species. The ribosomes of microsporidia resemble prokaryotic ribosomes in terms of size but lack a 5.8S subunit (3). The microsporidia infect many different animals and insects, but human infections were rarely reported before the HIV/AIDS epidemic when Enterocytozoon bieneusi was shown to be a major cause of diarrhea in patients with low CD4+ lymphocyte counts (4). Since then, 14 other species of microsporidia have been reported to infect the human gastrointestinal tract, eye, or muscle and to cause disseminated infection, most commonly in immunocompromised hosts (5–12). We report an infection by Tubulinosema sp. in an immunosuppressed patient.

Our patient was a 67-year-old woman with known high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma since 1993 and chronic lymphocytic leukemia since 2003. She had received multiple courses of chemotherapy, including fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, pentostatin, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone, and alemtuzumab. During 2004 through 2008, she had multiple hospitalizations with neutropenic complications. Her chemotherapy regimen was switched to bendamustine and cyclophosphamide in January 2009 because of persistent neutropenia.

In February 2009, the patient was hospitalized with fever and abdominal pain. No clear infectious etiology could be ascertained despite an extensive workup; she was treated with cefepime, vancomycin, and metronidazole without any improvement. At the end of the antimicrobial drug course, she noticed 2 painful white lesions on her tongue and also had fever and chills. The lesions consisted of two 1.0- × 1.5-cm nodules on the anterior aspect of the tongue. These were initially treated as oral thrush with fluconazole without resolution. At the same time, the patient experienced a relapse of herpes zoster that was treated with valacyclovir.

In April 2009, biopsy samples of the lesions were obtained. Results of the initial histopathology report were consistent with an inflamed granulation type tissue with collections of epithelioid histiocytes resembling naked-type granulomatous changes. Numerous intracellular microorganisms were seen in the myocytes. Culture for bacteria and fungi was negative and culture for microsporidia was not attempted. Serologic test results for Toxoplasma gondii and Trypanosoma cruzi were also negative.

Paraffin-fixed tissue and slides were sent to the laboratories of the Parasitic Diseases Branch and the Infectious Disease Pathology Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA, USA. Detailed results of the evaluations performed at CDC are given below. On the basis of a preliminary diagnosis of microsporidia, the patient was treated with albendazole 400 mg daily without any improvement.

In June 2009, the patient sought treatment for decreased urine output and acute kidney injury attributed to acute interstitial nephritis of unknown etiology based on eosinophils in her urine. A renal biopsy showed lymphocytic infiltrates negative for CD5 and CD20 and positive for paired box gene-5 and p53 expression, consistent with Richter’s transformation of the kidney. She was also found to have anterior mediastinal lymphadenopathy, interval increase in splenomegaly, ascites, pleural effusions, and bilateral interstitial infiltrates. Specimens from a bronchoscopy did not show any evidence of malignancy. Cultures were negative for bacteria and fungi. The patient died the next day. The family chose not to have an autopsy done. The cause of death was transformed chronic lymphocytic leukemia with acute renal failure as a contributory cause.

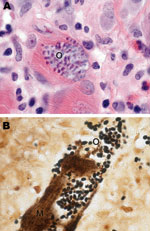

Muscle tissue after fixation was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, mucicarmine, Grocott methenamine silver, Giemsa, Warthin-Starry silver, acid-fast, and Lillie-Twort Gram stains. Granulomatous inflammation with focal infiltrates by neutrophils and eosinophils was seen. Within the myofibrils, there were abundant clusters of small, ovoid, basophilic organisms (Figure 1, panel A) measuring 2 µm stained positive by Lillie-Twort Gram and Warthin-Starry stains (Figure 1, panel B). The organisms stained faintly with Giemsa and were negative by Grocott methenamine silver, periodic acid–Schiff, and mucicarmine stains.

Results of immunohistochemical analysis (immune alkaline phosphatase technique) were negative, and autoimmune histochemical analysis was not performed. The primary antibodies used in the tests were an antibody against T. cruzi and an antibody against T. gondii. Appropriate positive and negative controls were run in parallel.

Electron microscopy at CDC revealed numerous spores but few developing stages (Figure 2, panel A). All stages were in direct contact with the host cell cytoplasm. The spores ranged from 1.4 to 2.4 μm in length and were characterized by an outer electron-dense exospore and a thick electron-lucent endospore. Within the endospore, a thin plasma membrane surrounded the polar filament coils and a polaroplast. These features are diagnostic characteristics of microsporidia. The endospore was considerably thinner near the anchoring disk. The polar filament had 11 coils arranged mostly in single rows, although in a few spores double rows were also seen. Three of the coils were slightly smaller than the others, which indicated the polar filaments are anisofilar (Figure 2, panel B). The polar filament coils measured 83.3–102 nm. At higher magnification, the polar filament coil exhibited a lucent ring around a dense core (Figure 2, panel C). A salient feature of the spore was the presence of a diplokaryotic nucleus with 2 nuclei closely opposed in a coffee bean–like appearance. The cytoplasm surrounding the nucleus was densely packed with ribosomes. Additional morphologic features included a posterior vacuole (Figure 2, panel B) and lamellar polaroplast consisting of tightly coiled membranes encircling the polar filament (Figure 2, panel D).

Molecular analysis was performed on a specimen of human muscle only. Taxonomically, the isolated spores’ small subunit of rRNA sequence on BLAST analysis (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) was found to be 100% identical (within a 500-nt sequenced fragment) to Tubulinosema acridophagus (GenBank accession no. AF024658), which usually infects North American grasshoppers (Schistocerca americana and Melanoplus spp.). It was also 96% identical to that of Tu. ratisbonensis (GenBank accession no. AY695845) obtained from a Drosophila melanogaster fruit fly and to Tu. kingi (GenBank accession no. DQ019419 and L28966) obtained from a D. willistoni fruit fly (Table).

We report a case of microsporidian myositis caused by Tubulinosema sp. in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and subsequent Richter’s transformation. Franzen et al. in 2005 proposed a new genus and species (13), Tu. ratisbonensis, for a microsporidium that parasitizes the fruit fly D. melanogaster. Subsequently, phylogenetic analyses of ribosomal RNA sequences determined that Tu. ratisbonensis was similar to several species included in the genus Nosema (13). Two other species of Nosema (N. kingi and N. acridophagus), both parasites of insects fitting the generic description of Tubulinosema, were transferred to the new genus (13). On the basis of limited ultrastructural studies, the microsporidia described here resemble Tu. acridophagus, Tu. kingi, and Tu. ratisbonensis (Table). Moreover, PCR of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue showed that it was closely related to Tu. acridophagus, a parasite of the fruit fly D. melanogaster, suggesting an insect source of this infection.

To the best of our knowledge, before this case microsporidia belonging to the genus Tubulinosema had not been associated with human infection. However, members of another genus Anncaliia (Brachiola), recently classified under the same family Tubulinosematidae as Tubulinosema, have been known to cause myositis and keratitis in humans (14). A. algerae is a well known parasite of mosquitoes and has also been described as causing infections in humans (15). Currently, microsporidia belonging to 8 genera are known to cause human infections (4). Therefore, clinicians managing immunodeficient patients who have fatigue, weakness, and other nonspecific symptoms, including unexplainable lesions, should consider microsporidiosis as a possible differential diagnosis.

Dr Choudhary is a second-year resident in internal medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Cleveland, Ohio. Her research interests include transplant infections.

References

- Vossbrinck CR, Maddox JV, Friedman S, Debrunner-Vossbrinck BA, Woese CR. Ribosomal RNA sequence suggests microsporidia are extremely ancient eukaryotes. Nature. 1987;326:411–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hirt RP, Logsdon JM Jr, Healy B, Dorey MW, Doolittle WF, Embley TM. Microsporidia are related to fungi: evidence from the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II and other proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:580–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Weiss LM. Molecular phylogeny and diagnostic approaches to microsporodia. Contrib Microbiol. 2000;6:209–35. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Didier ES, Stovall ME, Green LC, Brindley PJ, Sestak K, Didier PJ. Epidemiology of microsporidiosis: sources and modes of transmission. Vet Parasitol. 2004;126:145–66. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Curry A, Beeching NJ, Gilbert JD, Scott G, Rowland PL, Currie BJ. Trachipleistophora hominis infection in the myocardium and skeletal muscle of a patient with AIDS. J Infect. 2005;51:e139–44. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Weber R, Bryan RT, Schwartz DA, Owen RL. Human microsporidia infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:426–61.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sax PE, Rich JD, Pieciak WS, Trnka YM. Intestinal microsporidiosis occurring in a liver transplant recipient. Transplantation. 1995;60:617–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rabodonirina M, Bertocchi M, Desportes-Livage I, Cotte L, Levrey H, Piens MA, Enterocytozoon bieneusi as a cause of chronic diarrhea in a heart-lung transplant recipient who was seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:114–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gumbo T, Hobbs RE, Carlyn C, Hall G, Isada CM. Microsporidia infection in transplant patients. Transplantation. 1999;67:482–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mohindra AR, Lee MW, Visvesvara G, Moura H, Parasuarman R, Leitch GJ, Disseminated microsporidiosis in a renal transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2002;4:102–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bryan RT. Schwrtz. Epidemiology of microsporidiosis. In: Wittner M, Weiss LM, editors. The microsporidia and microsporidiosis. Washington: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. p. 502–16.

- Deplazes P, Mathis A, Weber R. Epidemiology and zoonotic aspects of microsporidia of mammals and birds. Contrib Microbiol. 2000;6:236–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Franzen C, Fischer S, Schroeder J, Schölmerich J, Schneuwly S. Morphological and molecular investigations of Tubulinosema ratisbonensis grn. nov., sp. nov. (Microsporidia: Tubulinosematidae fam. nov.), a parasite infecting a laboratory colony of Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera: Drosophilidae). J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2005;52:141–52. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Coyle CM, Weiss LM, Rhodes LV III, Cali A, Takvorian PM, Brown DF, Fatal myositis due to the microsporidian Brachiola algerae, a mosquito pathogen. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:42–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Visvesvara GS, Moura H, Leitch GJ, Schwartz DA, Xiao LX. Public health importance of Brachiola algerae – an emerging pathogen of humans. Folia Parasitol (Praha). 2005;52:83–94.PubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Table

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 17, Number 9—September 2011

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Maria M. Choudhary, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Department of Internal Medicine, 9500 Euclid Foundation, NA10, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA

Top