Volume 19, Number 3—March 2013

Dispatch

Lymphogranuloma Venereum in Men Screened for Pharyngeal and Rectal Infection, Germany

Abstract

To determine prevalence of lymphogranuloma venereum among men who have sex with men in Germany, we conducted a multicenter study during 2009–2010 and found high rates of rectal and pharyngeal infection in men positive for the causative agent, Chlamydia trachomatis. Many infections were asymptomatic. An adjusted C. trachomatis screening policy is justified in Germany.

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is a sexually transmitted disease caused by infection with Chlamydia trachomatis bacteria, genotypes L1–L3. An outbreak of proctitis cases caused by C. trachomatis genotype L2 in men who have sex with men (MSM) became apparent in the Netherlands in 2003; subsequently, awareness of this disease increased throughout Europe (1).

In the United Kingdom and the United States, guidelines recommend rectal C. trachomatis screening for MSM (2). In Germany, no screening recommendations for asymptomatic MSM exist, and nationally, no C. trachomatis prevalence data are available. We investigated the prevalence of pharyngeal and rectal C. trachomatis infection and LGV among MSM in Germany.

We conducted a prospective, multicenter study during December 1, 2009–December 31, 2010, by recruiting a convenience sample of MSM at sentinel sites for sexually transmitted infections throughout Germany. Inclusion criteria were being MSM, having >1 male sexual partner within the previous 6 months, and agreeing to provide a rectal and/or pharyngeal swab specimen. To measure factors associated with HIV status, enrollment at sites providing HIV care was enhanced.

Rectal and pharyngeal specimens were collected according to standardized protocols; urine testing or collection of urethral swabs was optional. All specimens were sent to a privately owned laboratory (Laboratoriumsmedizin Koeln, Cologne, Germany), and tested for C. trachomatis by using the APTIMA Combo 2 Assay (GenProbe Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), based on RNA amplification. Specimens positive for C. trachomatis were sent to the Institute of Medical Microbiology and Hospital Hygiene of Heinrich-Heine University in Duesseldorf, Germany, for L genotyping, based on a DNA test (3). Persons who had a sample positive for LGV genotype L were defined as LGV-positive; those positive for other genotypes were defined as LGV-negative.

Data on sexual history, behavior, and symptoms were collected from participants through a self-administered questionnaire. Information on HIV status was self-reported or obtained from primary care providers. Results were assessed with 95% CIs, and significance level was set at 0.05. The study protocol was approved by the ethical review committee of Charité University Hospital, Berlin. Data were anonymized, participation was voluntary, and no financial incentives were provided.

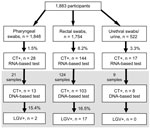

Of 1,883 MSM recruited at 22 sites in 16 cities, 1,848 agreed to a pharyngeal swab and 1,754 to a rectal swab. An additional 522 samples from either urine or urethral swab were obtained. Of those recruited, 166 (8.8%) tested positive for C. trachomatis by rRNA-based assay (Figure). A total of 632 (33.6%) participants were HIV-positive. C. trachomatis prevalence was 10.8% among HIV-positive and 7.8% among HIV-negative or untested participants (odds ratio [OR] 1.42, 95% CI 1.03–1.96).

For logistical reasons, only 154 C. trachomatis–positive specimens underwent genotyping. Nineteen samples were LGV-positive: 17 genotype L2 (16 rectal, 1 pharyngeal), 1 genotype L3 (pharyngeal), and 1 genotype L2/L3 (rectal). For genotyped specimens, LGV prevalence was 16.5% in rectal specimens and 15.4% in pharyngeal specimens. Overall, LGV prevalence was 1.7% (11/632) among HIV-positive and 0.6% (8/1,251) among HIV-negative or untested MSM (OR 2.75, 95% CI 1.10–6.88).

Eight (53.3%) of 15 LGV-positive MSM did not report recent rectal symptoms (Table 1). HIV-negative MSM more often met 1 of their last 3 sexual partners in a bar, pub, or club than did HIV-negative MSM (p = 0.03 by t test). However, we found no substantial differences in sexual practices between HIV-positive and HIV-negative MSM positive for LGV and no differences between LGV-positive and LGV-negative MSM (data not shown).

Overall, 70.2% of C. trachomatis–positive MSM were asymptomatic (Table 2). In multivariable logistic regression analysis, only history of C. trachomatis infection was associated with LGV infection. In a model not considering history of C. trachomatis infection, the number of male sex partners in the previous 6 months was associated with outcome (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.06).

Our study showed rectal and pharyngeal LGV prevalences of 16.5% and 15.4%, respectively, among C. trachomatis–positive MSM in Germany. Previous reports have found that 75% of all LGV cases in MSM were among HIV-positive men (1,4); a meta-analysis found HIV prevalence of 67%–100% among LGV-positive men (5). In our study, 58% of LGV-positive MSM were HIV positive.

In a screening study conducted in London, an 8% (247/3,017) prevalence of rectal chlamydia was detected; among these infections, 14% were L genotype (6). The co-infection rate of HIV in men with rectal C. trachomatis in that study was 38% (94/247), comparable to the 44% in our study. HIV-positive status may be associated with having more sexual partners, more frequent unprotected receptive anal intercourse, and higher susceptibility to LGV infection (4). Because of a relatively small number of observations, however, our study lacks the power to detect these differences.

Although the finding was not significant, HIV-negative MSM who had higher numbers of sexual partners in the 6 months before the study were more likely to be LGV-positive. These men were also more likely to having met 1 of their previous 3 partners in a bar, pub, or club, settings in which explicit HIV serostatus communication is less likely to occur (7). This finding indicates that the spread of LGV is not confined to sex networks of HIV-positive MSM (8).

The prevalence of rectal and pharyngeal C. trachomatis infection we found in MSM in Germany is comparable to previously reported rates (9–11). However, because our study used a convenience sample of health care–seeking men, MSM who have poor health care–seeking behavior might be underrepresented, which could mean C. trachomatis prevalence is higher than we found. A total of 70% of C. trachomatis–positive persons in our study were asymptomatic, similar to the 69% reported from a study in the United Kingdom (6).

Our observed proportion of LGV subtypes among C. trachomatis–positive persons is in line with published data (6). However, the high proportion of asymptomatic cases and LGV-positive cases among HIV-negative MSM we found is in contrast to other recent findings (6,12), although considerable percentages of asymptomatic LGV infections have been reported elsewhere (13).

Although it is not licensed for extragenital use, sensitivity and specificity of the RNA-based assay we used is high (10,14). Nucleic acid amplification tests may also be used for detection of C. trachomatis in pharyngeal and rectal specimens (15). Our initial testing used the APTIMA Combo 2 Assay, for which the transport media was adopted. Because of the lysing effect of the transport medium, concentration of pathogens before DNA preparation was disqualified and C. trachomatis detection was restricted to samples with higher DNA concentrations, leading to a different number of positive samples. To avoid potential bias, only specimens that tested positive in both assays were included in the analyses.

Another limitation of our study is that not all 166 samples were sent for further subtyping. The genotype for 12 specimens remains unknown.

We found no major predictors for LGV infections in C. trachomatis–positive MSM. This finding points to 2 options for control: 1) all MSM diagnosed with C. trachomatis should receive treatment adequate to cure LGV (that is, 3 weeks of doxycycline rather than 1), or 2) all MSM-derived specimens positive for C. trachomatis should further be genotyped to exclude infection with LGV genotypes. Physicians should be aware of possible L-genotype infection in symptomatic or HIV-positive patients and should initiate further diagnostic tests. In the absence of commercially available LGV sequencing tests, clinicians should use in-house PCR tests to detect LGV strains. In addition, the observed rate of rectal C. trachomatis and LGV infections in MSM justifies the implementation of a C. trachomatis screening policy for MSM in Germany.

Dr Haar is a scientist in the HIV/AIDS, STI and Bloodborne Infections Unit in the Department for Infectious Disease Epidemiology at Robert Koch-Institute in Berlin, Germany. Her primary research interests are in the epidemiology and biobehavioural surveillance of Chlamydia trachomatis and other sexually transmitted infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the PARIS (Pharyngeal And Rectal Infection Screening) study group for conducting data collection: Anja Potthoff, Aspasia Manos, Gisela Hanf, Norbert Kellermann, Petra Spornraft-Ragaller, Andreas Klein, Ruth Hörnle, Karin Rittner, Kathrin Graefe, Gisela Walter, Esther Voigt, Vera Pawassarat, Heiko Jessen, Carmen Zedlack, Werner Becker, Corinna Becker, Manuela Buttelmann, Felix Laue, Marc Grenz, Gaby Knecht, Gert Hartmann, Peter Wiesel, Heribert Knechten, Petra Panstruga, Albert Mayer, Florian Zinke, and Torben Schultes. We also thank Ramona Scheufele for her assistance with statistical analyses; Marion Steinmetz, Eva Schorn, Nadine Moebius, and Meike Rosenblatt for their technical help; and Osamah Hamouda for his valuable comments.

This work was supported by the research funds of the Robert Koch-Institute. Test kits for detection of C. trachomatis infection were provided free of charge by the manufacturer.

The authors are aware that the conclusion regarding implementation of C. trachomatis screening policies will have financial impacts for companies producing respective diagnostic tests. However, neither GenProbe nor any of its employees had any influence on the analysis and interpretation of the data or on the conclusions. None of the authors has any shares or other investments in companies producing diagnostic tests for C. trachomatis or LGV. H.W., F.W., and B.H. work in medical laboratories that also offer C. trachomatis and/or LGV testing on a commercial basis and therefore may financially benefit from broadening C. trachomatis screening recommendations to MSM; none of them, however, has any influence on the decision-making process of health authorities in Germany.

References

- Dougan S, Evans BG, Elford J. Sexually transmitted infections in Western Europe among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:783–90 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. Sexually transmitted infections: UK national screening and testing guidelines. Bacterial Special Interest Group of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV Clinical Effectiveness Group. 2006 [cited 2012 Dec 12]. http://www.bashh.org/documents/59/59.pdf

- Schaeffer A, Henrich B. Rapid detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and typing of the lymphogranuloma venereum associated L-serovars by TaqMan PCR. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:56. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Martin-Iguacel R, Llibre JM, Nielsen H, Heras E, Matas L, Lugo R, Lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis: a silent endemic disease in men who have sex with men in industrialised countries. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:917–25. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rönn MM, Ward H. The association between lymphogranuloma venereum and HIV among men who have sex with men: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Annan NT, Sullivan AK, Nori A, Naydenova P, Alexander S, McKenna A, Rectal chlamydia—a reservoir of undiagnosed infection in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:176–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Velter A, Bouyssou-Michel A, Arnaud A, Semaille C. Do men who have sex with men use serosorting with casual partners in France? Results of a nationwide survey (ANRS-EN17-Presse Gay 2004). Euro Surveill. 2009;14:19416 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bremer V, Meyer T, Marcus U, Hamouda O. Lymphogranuloma venereum emerging in men who have sex with men in Germany. Euro Surveill. 2006;11:152–4 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinic-based testing for rectal and pharyngeal Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infections by community-based organizations—five cities, United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:716–9 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ota KV, Tamari IE, Smieja M, Jamieson F, Jones KE, Towns L, Detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis in pharyngeal and rectal specimens using the BD Probetec et system, the Gen-Probe Aptima Combo 2 Assay and culture. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:182–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Currie MJ, Martin SJ, Soo TMFJB. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhoea in men who have sex with men in clinical and non-clinical settings. Sex Health. 2006;3:123–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Korhonen S, Hiltunen-Back E, Puolakkainen M. Genotyping of Chlamydia trachomatis in rectal and pharyngeal specimens: identification of LGV genotypes in Finland. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88:465–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Spaargaren J, Fennema HS, Morre SA, de Vries HJ, Coutinho RA. New lymphogranuloma venereum Chlamydia trachomatis variant, Amsterdam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1090–2 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schachter J, Moncada J, Liska S, Shayevich C, Klausner JD. Nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of chlamydial and gonococcal infections of the oropharynx and rectum in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:637–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. Chlamydia trachomatis UK testing guidelines. Clinical Effectiveness Group of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. 2010 [cited 2012 Dec 12]. http://www.bashh.org/documents/3352

Figure

Tables

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 19, Number 3—March 2013

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Karin Haar, Department for Infectious Disease Epidemiology, HIV/AIDS, STI and Bloodborne Infections Unit, Robert Koch-Institute, DGZ-Ring 1, 13086 Berlin, Germany

Top