Volume 29, Number 10—October 2023

Research Letter

Bacillus subtilis Bacteremia from Gastrointestinal Perforation after Natto Ingestion, Japan

Abstract

We report a case of Bacillus subtilis variant natto bacteremia from a gastrointestinal perforation in a patient who ingested natto. Genotypic methods showed the bacteria in a blood sample and the ingested natto were the same strains. Older or immunocompromised patients could be at risk for bacteremia from ingesting natto.

Bacillus subtilis is a gram-positive, rod-shaped, spore-forming bacterium with low pathogenicity (1). B. subtilis isolated from clinical specimens is sometimes considered a contaminant (2). However, a few cases of bacteremia caused by B. subtilis have been reported in Japan (3–6). We report a case of B. subtilis variant natto bacteremia and peritonitis caused by ingestion of natto, a traditional fermented food in Japan that is prepared by adding B. subtilis var. natto culture to soybeans and fermenting them.

A 65-year-old man with metastatic colorectal cancer was admitted to Oita University Hospital (Oita, Japan) with fever and perianal pain. Approximately 2 months before admission, he began chemotherapy with bevacizumab and modified oxaliplatin plus leucovorin plus 5-fluorouracilm (FOLFOX6). Six days before admission, on day 4 after the third course of chemotherapy, he experienced perianal pain. He had a history of diabetes mellitus and a custom of eating natto.

The patient’s body temperature was 37.6°C, blood pressure was 132/84 mm Hg, and heart rate was 70 beats/min. A physical examination revealed lower abdominal pain. Laboratory tests revealed an elevated leukocyte count (15,150 cells/μL), elevated C-reactive protein level (20.2 mg/dL), and elevated procalcitonin level (0.55 ng/mL). Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography showed free air in the perisigmoid colon, an intraabdominal abscess, and slight ascites. Peritonitis caused by sigmoid colon perforation was diagnosed, and a transverse colostomy and drainage were performed. After blood and pus cultures were collected, a course of intravenous meropenem (0.5 g every 8 h) was initiated.

On day 3, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics, https://www.bruker.com) of the blood culture revealed B. subtilis (MALDI-TOF score 2.224), and the pus culture revealed polymicrobial bacteria, including B. subtilis. We performed antimicrobial resistance testing on a dry plate (Eiken Chemical Co., https://www.eiken.co.jp) by using the broth microdilution method and then analyzed images by using a Koden IA40MIC-i (Koden, https://koden.jp). MICs were as follows: cefazolin, <0.25 µg/mL; cefotiam, 0.5 µg/mL; meropenem, <0.25 µg/mL; clindamycin, 0.5 µg/mL; levofloxacin <0.25 µg/mL; minocycline, <0.25 µg/mL; and vancomycin, <0.5 µg/mL. Meropenem was administered for a total of 10 days. On day 36, additional computed tomography–guided percutaneous drainage was performed, and on day 66, the patient was discharged from the hospital after rehabilitation.

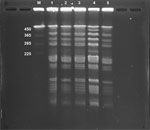

We assessed whether blood and pus culture isolates and the isolate from natto the patient consumed (brand A) were the same strain, by using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), as previously described (7). To verify B. subtilis var. natto, we tested 2 brands (brands B and C) besides brand A that the patient reported consuming. PFGE revealed that the isolates detected from the blood and pus cultures were the same as the cultures of natto brand A that the patient consumed. Moreover, those isolates were the same as isolates from natto brand C (Figure), suggesting that the blood and pus culture isolates were B. subtilis var. natto.

Other than B. subtilis var. natto, B. subtilis has multiple other subspecies: B. subtilis subsp. subtilis, B. subtilis subsp. spizizenii, B. subtilis subsp. inaquosrum, and B. subtilis subsp. stercoris. Distinguishing between those species by 16S rRNA gene sequencing and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry can be difficult (8). The most common known portal of entry for B. subtilis bacteria is the gastrointestinal tract, but often the site of entry is unknown, and bacteremia that has a gastrointestinal tract source is presumed to be related to natto ingestion (3–6). However, B. subtilis var. natto was identified in only 2 prior cases, 1 that analyzed the draft whole-genome of each B. subtilis strain using next-generation sequencing (6) and 1 that used the biotin gene and the biotin requirement test (5). In our case, PFGE analysis revealed that the patient’s isolate was B. subtilis var. natto that matched the natto brand he consumed. Although B. subtilis bacteremia has been reported only in Japan thus far, the popularity of Japanese cuisine is increasing worldwide (9). Therefore, clinicians outside Japan should also be aware of B. subtilis bacteremia caused by natto consumption.

PFGE analysis revealed that the natto of brands A and B contained different bacterial strains. Many brands of natto are sold in Japan. Each brand uses different soybean cultivars, processing conditions (soaking, steaming, and fermentation), and B. subtilis var. natto strains (10). Therefore, a history of natto consumption alone might not be associated with the cause of B. subtilis bacteremia because eating natto is not uncommon among the population of Japan.

In conclusion, we report a case of B. subtilis bacteremia and secondary peritonitis resulting from gastrointestinal perforation in a patient who ingested natto. Our case and others in the literature indicate that older or immunocompromised patients who consume natto are at risk for serious infection from natto (4,6). Clinicians should advise patients in these risk groups to avoid eating natto or food products containing B. subtilis bacteria.

Dr. Hashimoto is a physician at the Infection Control Center of Oita University Hospital. His main research interest is in microbiology.

References

- Oggioni MR, Pozzi G, Valensin PE, Galieni P, Bigazzi C. Recurrent septicemia in an immunocompromised patient due to probiotic strains of Bacillus subtilis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:325–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Weber DJ, Saviteer SM, Rutala WA, Thomann CA. Clinical significance of Bacillus species isolated from blood cultures. South Med J. 1989;82:705–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hashimoto T, Hayakawa K, Mezaki K, Kutsuna S, Takeshita N, Yamamoto K, et al. Bacteremia due to Bacillus subtilis: a case report and clinical evaluation of 10 cases [in Japanese]. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 2017;91:151–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Aoyagi R, Okita K, Uda K, Ikegawa K, Yuza Y, Horikoshi Y. Natto intake is a risk factor of Bacillus subtilis bacteremia among children undergoing chemotherapy for childhood cancer: A case-control study. J Infect Chemother. 2023;29:329–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tanaka I, Kutsuna S, Ohkusu M, Kato T, Miyashita M, Moriya A, et al. Bacillus subtilis variant natto Bacteremia of Gastrointestinal Origin, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:1718–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kato A, Yoshifuji A, Komori K, Aoki K, Taniyama D, Komatsu M, et al. A case of Bacillus subtilis var. natto bacteremia caused by ingestion of natto during COVID-19 treatment in a maintenance hemodialysis patient with multiple myeloma. J Infect Chemother. 2022;28:1212–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Marten P, Smalla K, Berg G. Genotypic and phenotypic differentiation of an antifungal biocontrol strain belonging to Bacillus subtilis. J Appl Microbiol. 2000;89:463–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rooney AP, Price NP, Ehrhardt C, Swezey JL, Bannan JD. Phylogeny and molecular taxonomy of the Bacillus subtilis species complex and description of Bacillus subtilis subsp. inaquosorum subsp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:2429–36. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Watari T, Tachibana T, Okada A, Nishikawa K, Otsuki K, Nagai N, et al. A review of food poisoning caused by local food in Japan. J Gen Fam Med. 2020;22:15–23. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Escamilla DM, Rosso ML, Holshouser DL, Chen P, Zhang B. Improvement of soybean cultivars for natto production through the selection of seed morphological and physiological characteristics and seed compositions: a review. Plant Breed. 2019;138:131–9. DOIGoogle Scholar

Figure

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 29, Number 10—October 2023

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Takehiro Hashimoto, Infection Control Center, Oita University Hospital, 1-1 Idaigaoka, Hasama-machi, Yufu, Oita 879-5593, Japan

Top