Volume 17, Number 11—November 2011

THEME ISSUE

CHOLERA IN HAITI

Letter

Understanding the Cholera Epidemic, Haiti

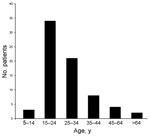

To the Editor: After the devastating outbreak of cholera in Haiti in mid-October 2010, several hypotheses have emerged regarding the origin of the outbreak. Some articles and media reports pointed to the United Nations peacekeepers from Nepal as the source. Piarroux et al. drew a similar conclusion from their epidemiologic study (1). Nepal did experience an outbreak of cholera during August–October 2010, in which 72 cases of infection with Vibrio cholerae O1, serotype Ogawa, were confirmed, mostly among young adult males. The cases peaked from mid-September to early October (Figure; Figure A1), and no deaths occurred. Despite this similarity in timing, I believe several points need to be considered before a firm conclusion is reached.

Cholera strains isolated in Haiti were genetically most similar to strains detected in Bangladesh in 2002 and 2008; thus, cholera was most likely introduced into Haiti from southern Asia (2). Despite the genetic similarity in the strains, no attempt was made by the researchers to ascertain and rule out the source of the outbreak in Bangladeshi policemen stationed at Mirebalais between September and October 2010. Another, although less likely, source for the introduction of cholera into Haiti could have been travelers or relief workers who may have recently been to southern Asia. Most relief workers probably come from countries without endemic cholera, but they cannot definitely be ruled out as a source of cholera in Haiti. For example, in industrialized countries, cholera has been detected among travelers, albeit in smaller numbers, returning home from cholera-endemic areas (3,4). However, Piarroux et al. offered no information about travelers or relief workers or whether they had been screened for V. cholerae infection before coming to Haiti (1). Of note, the United Nations reported that none of the Nepalese peacekeepers was found to be positive for the strain in Haiti (5); hence, other possible explanations for the origin of the outbreak simply cannot be overlooked.

References

- Piarroux R, Barrais R, Faucher B, Haus R, Piarroux M, Gaudart J, Understanding the cholera epidemic, Haiti. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1161–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chin CS, Sorenson J, Harris JB, Robins WP, Charles RC, Jean-Charles RR, The origin of the Haitian cholera outbreak strain. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:33–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tarantola A, Ioos S, Rotureau B, Paquet C, Quilici ML, Fournier JM. Retrospective analysis of the cholera cases imported to France from 1973 to 2005. J Travel Med. 2007;14:209–14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- National Travel Health Network and Centre. Travel health information sheets; updated October, 2010: cholera. Health Protection Agency [cited 2011 Jun 28]. http://www.nathnac.org/pro/factsheets/cholera.htm

- United Nations. Press conference by Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, December 15, 2010 [cited 2011 Jun 28]. http://www.un.org/News/briefings/docs/2010/101215_Guest.doc.htm

Figures

Cite This ArticleRelated Links

In Response: We read with great interest the letter by Pun, which suggests that Bangladeshi policemen in Mirebalais could have introduced cholera into Haiti (1). However, we want to emphasize that the first Haitian cholera case occurred in Meille, just next to the Nepalese military camp—not in Mirebalais or Hinche, where Bangladeshi policemen served. The location of the first case was stated in our article (2) and confirmed by the United Nations (UN) panel of experts on the cholera outbreak in Haiti (3). The UN panel also reported that major sanitation deficiencies likely resulted in contamination of a stream flowing within a few meters of the Nepalese camp. No other humanitarian forces were working in the small hamlet of Meille.

As acknowledged by Pun, Nepalese soldiers left for Haiti just when a cholera epidemic was raging in their country. According to the UN panel report, “a careful analysis of the MLVA [multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis] results and the ctxB gene indicated that the strains isolated in Haiti and Nepal during 2009 were a perfect match.” Nepalese strains had been made available to the UN Panel from the International Vaccine Institute in Seoul, South Korea (3).

Referring to UN press conferences, Pun stated that “none of the Nepalese peacekeepers was found to be positive for the [V. cholerae] strain in Haiti.” However, it should be remembered that no testing of the soldiers was performed. Although the UN panel reported that “no cases of severe diarrhea and dehydration occurred among MINUSTAH [United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti] personnel during this period,” the panel provided no information concerning mild or moderate diarrhea.

Overall, evidence overwhelmingly supports the conclusion that the UN military camp in Meille was the source of the Haitian cholera epidemic. The person who brought cholera into Haiti could not be identified because of the lack of an early, independent investigation in the camp.

References

- Pun SB. Understanding the cholera epidemic, Haiti [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:2178–9.

- Piarroux R, Barrais R, Faucher B, Haus R, Piarroux M, Gaudart J, Understanding the cholera epidemic, Haiti. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1161–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cravioto A, Lanata CF, Lantagne DS, Nair GB. Final report of the independent panel of experts on the cholera outbreak in Haiti [cited 2011Sep 2]. http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/haiti/UN-cholera-report-final.pdf

Table of Contents – Volume 17, Number 11—November 2011

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|