Volume 18, Number 9—September 2012

Dispatch

Antimicrobial Drug Use and Macrolide-Resistant Streptococcus pyogenes, Belgium

Abstract

In Belgium, decreasing macrolide, lincosamide, streptogramins B, and tetracycline use during 1997–2007 correlated significantly with decreasing macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes during 1999–2009. Maintaining drug use below a critical threshold corresponded with low-level macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes and an increased number of erm(A)-harboring emm77 S. pyogenes with low fitness costs.

Macrolide resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes results primarily from modification of the drug target site by methyltransferases encoded by erm genes, erm(A) and erm(B) or by active efflux mediated by a mef-encoded efflux pump. Of these, erm(A) is inducibly expressed (1) and generally confers low-level resistance to macrolides, whereas lincosamides and streptogramins B (MLSB), which share overlapping binding sites, remain active against erm(A)-harboring S. pyogenes (2). Conversely, erm(B) can be constitutively or inducibly expressed and confers high-level resistance to MLSB (2). mef(A) also is constitutively expressed but confers low to moderate resistance to 14- and 15-membered macrolides and susceptibility to 16-membered MLSB (2).

That macrolide use is the main driver of macrolide resistance in streptococci has been well demonstrated at the population and individual levels (3,4). Because erm and mef are cocarried with tet genes on mobile elements, tetracycline use also affects macrolide resistance (4). In addition, acquisition of resistance often confers a cost to bacteria, the magnitude of which is the main parameter influencing the rate of development and stability of the resistance mechanisms and, conversely, the rate at which resistance would decrease under decreasing use of antimicrobial drugs (5). We investigated temporal changes in the molecular epidemiology of macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes during 1999–2009 in relation to strain fitness (i.e., ability of bacteria to survive and reproduce) and to outpatient use of MLSB and tetracycline in Belgium.

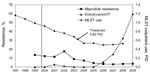

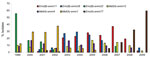

We screened 11,819 S. pyogenes isolates from patients with tonsillopharyngitis or invasive disease in Belgium during 1999−2009 for macrolide resistance. We used double-disk diffusion, MIC testing, and multiplex PCR to detect erm and mef genes and investigated their clonality by emm typing and by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (6). The prevalence of macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes decreased from 13.5% to 3.3% during 1999−2006 and remained low from 2006 onward (Figure 1); most isolates harbored erm(B) (395 [46.5%]) or mef(A) (383 [45.1%]). We detected erm(A) in only 85 (10.0%) resistant strains; however, their proportions among macrolide-resistant strains increased from 1 (1.2%) of 81 in 1999 to 36 (76.6%) of 47 in 2009. erm(A)-harboring S. pyogenes isolates primarily belonged to emm77 (50/85[5.8%]). mef(A) was mostly associated with emm1, emm4, and emm12 and erm(B) with emm11, emm22, and emm28 (Figure 2). During 1999−2009, proportions of mef(A)- and erm(B)-associated emm types decreased gradually, whereas those of erm(A)-harboring emm77 (erm(A)-emm77) )increased steadily from 2006 onward (Figure 2). erm(A)-emm77 became predominant in 2008−2009, representing 10−28 (32.2%−59.6%) of total macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes isolates during those 2 years (Figure 1, Figure 2). Most (97.8%) erm(A)-emm77 belonged to the same pulsed-field gel electrophoresis cluster and harbored tet(O), indicating gene linkage.

Next, we used data on outpatient use of MLSB and tetracycline collected by the Belgian National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance during 1997−2008 and aggregated at the active substance level (World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Drug Statistics Methodology, www.whocc.no/atc/structure_and_principles/) to model the data obtained for macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes. MLSB and tetracycline use was expressed in packages/1,000 inhabitants/day, a better proxy for prescriptions than defined daily doses in Belgium, where the number of defined daily doses per package or prescription had increased during the previous decade (7). MLSB and tetracycline use decreased from 1997 to 2004 (1.16–0.53 packages/1,000 inhabitants/day) and remained stable at this level (0.50−0.53 packages/1,000 inhabitants/day) from 2004 onward (Figure 1). Total outpatient use of antimicrobial drugs also decreased (3.75–2.4 packages/1,000 inhabitants/day) during 1997–2007, as did use of penicillins, whereas proportional use of amoxicillin–clavulanate acid increased transiently soon after public campaigns began in Belgium (8). Yearly proportions of macrolide-resistant strains among total isolates correlated with MLSB and tetracycline use in generalized linear models with a negative binomial distribution and a log-link (GLM, PROC GENMOD, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Using an interval of 2 years, we observed a highly significant positive correlation between decreasing use of MLSB and tetracycline during 1997−2007 and decreasing levels of macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes during 1999−2009 (p<0.0001). The consistent decrease in MLSB and tetracycline use since 1997 was further accentuated by the start of public health campaigns in December 2000 that also were directed toward prescribers and successfully reduced antimicrobial drug prescribing in Belgium (Figure 1) (8). A similar trend was observed in Finland, where a nationwide increase in erythromycin use and resistant S. pyogenes led to issuance of national recommendations to reduce outpatient use of MLSB; erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes declined after 2 years of reduced MLSB use (9). Nonetheless, for S. pyogenes, these correlations are not always clear, primarily because of frequent clonal fluctuations for this organism. For instance, despite a 21% decrease in macrolide use in Slovenia, resistance doubled among noninvasive S. pyogenes isolates (10).

Notwithstanding clonal changes, the fitness costs (i.e., an organism’s decreased ability to survive and reproduce because of a genetic change, expressed as a decreased bacterial growth rate) associated with particular resistance mechanisms is another major factor governing the relation between use and resistance. Mathematical models have shown threshold levels of antimicrobial drug use below which the frequency of resistance would not increase if resistance imposes a fitness cost for the bacteria (11). We further hypothesized that the frequency of certain macrolide-resistant geno-emm-types might differ if antimicrobial drug use remains below a certain threshold. In concordance with the models, we found a negative correlation between use of MLSB and tetracycline and proportions of erm(A)-emm77 among macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes (p = 0.0002), and we identified 0.62 packages/1,000 inhabitants/day as the critical threshold volume of MLSB and tetracycline use below which proportions of erm(A)-emm77 among macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes would increase significantly (p<0.0001). Next, we compared the fitness of erm(A)-emm77 with that of 6 other major macrolide-resistant geno-emm-types in Belgium during 1999–2009 (Figure 2). After growth-competition experiments (12), initial and final proportions of competing strains were determined by multiplex PCR to detect erm(B), erm(A), or mef(A) in 50 randomly selected colonies per plated mixture. Number of generations and relative fitness of competed pairwise strains were calculated as described (13). The inducible erm(A) in an emm77 background was more fit (67%) than most of the geno-emm-types that predominated during the previous years of higher MLSB and tetracycline use (Table). Only the mef(A)-emm1 and erm(B)-emm28 geno-emm-types were equally as fit as erm(A)-emm77. Foucault et al. (14) showed that in the noninduced state, the inducible vanB gene had no effect on fitness of enterococci and might explain the low fitness cost of erm(A) carriage in emm77 strains. A predominance of erm(A)-harboring strains during 1993–2002, with 30% in an emm77 background, was also reported in Norway, a country with a low prevalence of resistance (2.7%) and antimicrobial drug use (15). Of note here is the combination of erm(A) and emm77 as geno-emm-type because the fitness benefit (i.e., lack of fitness cost) was not as remarkable for other erm(A)-harboring emm types (data not shown). The mechanisms underlying the higher fitness benefit conferred by an emm77 versus another emm background for the erm(A) genetic element remain to be investigated and might be related to differences in basal gene expression or compensatory changes in the emm77 genome or might result from differences in the genetic element harboring erm(A) in emm77.

Using macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes as a marker for use of MLSB and tetracycline, we showed a decrease in use of these antimicrobial drugs, accentuated by successful public health campaigns, reflected a steady decline of macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes in Belgium. Furthermore, successfully maintaining use below a critical threshold resulted in maintenance of low-level macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes and emergence of the inducibly expressed and low-level resistant erm(A)-emm77 geno-emm-type. Maintaining antimicrobial drug use below a critical threshold might facilitate stabilization of low-level antimicrobial drug resistance and of milder resistance mechanisms with lower fitness costs.

Ms Van Heirstraeten holds a master’s degree in biomedical sciences and is a final-year PhD student at the University of Antwerp. Her research interests include studying the epidemiology and molecular mechanisms of resistance in oral streptococci and developing molecular diagnostic tools for respiratory tract infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following centers for their participation in this study: Algemeen Medisch Laboratorium BVBA, Laboratoire de Biologie Clinique et Hormonale SPRL, Centraal Laboratorium, Medisch Centrum Huisarten, Centre Hospitalier de L'Ardenne Laboratoire de Biologie Clinique et de Ria, and Laboratoire Marchand.

Part of this work was presented at the 20th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, April 10–13, 2010, in Vienna, Austria, and at the 50th International Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, September 12–15, 2010, in Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

This study was partly funded by the Belgian Antibiotic Policy Coordination Committee.

References

- Malhotra-Kumar S, Mazzariol A, Van Heirstraeten L, Lammens C, de Rijk P, Cornaglia G, Unusual resistance patterns in macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes harbouring erm(A). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:42–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Leclercq R. Mechanisms of resistance to macrolides and lincosamides: nature of the resistance elements and their clinical implications. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:482–92. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet. 2005;365:579–87.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Malhotra-Kumar S, Lammens C, Coenen S, Van Herck K, Goossens H. Effect of azithromycin and clarithromycin therapy on pharyngeal carriage of macrolide-resistant streptococci in healthy volunteers: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2007;369:482–90. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Andersson DI, Hughes D. Antibiotic resistance and its cost: is it possible to reverse resistance? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:260–71.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Malhotra-Kumar S, Lammens C, Chapelle S, Wijdooghe M, Piessens J, Van Herck K, Macrolide- and telithromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes, Belgium, 1999–2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:939–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Adriaenssens N, Coenen S, Versporten A, Muller A, Minalu G, Faes C, European surveillance of antimicrobial consumption (ESAC): outpatient antibiotic use in Europe (1997–2009). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(Suppl 6):vi3–12. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Goossens H, Coenen S, Costers M, De Corte S, De Sutter A, Gordts B, Achievements of the Belgian Antibiotic Policy Coordination Committee (BAPCOC). Euro Surveill. 2008;13:pii: 19036.

- Seppälä H, Klaukka T, Vuopio-Varkila J, Muotiala A, Helenius H, Lager K, The effect of changes in the consumption of macrolide antibiotics on erythromycin resistance in group A streptococci in Finland. Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:441–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cizman M, Beovic B, Seme K, Paragi M, Strumbelj I, Muller-Premru M, Macrolide resistance rates in respiratory pathogens in Slovenia following reduced macrolide use. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;28:537–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Levin BR, Lipsitch M, Perrot V, Schrag S, Antia R, Simonsen L, The population genetics of antibiotic resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(Suppl 1):S9–16. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rozen DE, McGee L, Levin BR, Klugman KP. Fitness costs of fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:412–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gillespie SH, ed. Antibiotic resistance: methods and protocols (Methods in Molecular Medicine). Totowa (NJ): Humana Press; 2001.

- Foucault ML, Depardieu F, Courvalin P, Grillot-Courvalin C. Inducible expression eliminates the fitness cost of vancomycin resistance in enterococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16964–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Littauer P, Caugant DA, Sangvik M, Hoiby EA, Sundsfjord A, Simonsen GS. Macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes in Norway: population structure and resistance determinants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1896–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Table

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 18, Number 9—September 2012

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Surbhi Malhotra-Kumar, Laboratory of Medical Microbiology, Campus Drie Eiken, University of Antwerp, S6, Universiteitsplein 1, B-2610 Wilrijk, Belgium

Top