Volume 19, Number 2—February 2013

Dispatch

Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus in Ticks from Migratory Birds, Morocco1

Abstract

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus was detected in ticks removed from migratory birds in Morocco. This finding demonstrates the circulation of this virus in northwestern Africa and supports the hypothesis that the virus can be introduced into Europe by infected ticks transported from Africa by migratory birds.

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV), the causative agent of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHV), is an arthropod-borne virus (arbovirus) with clinical relevance worldwide (1). CCHF causes sudden onset of signs and symptoms including headache, high fever, back pain, joint pain, stomach pain, and vomiting, which can progress to severe bruising, severe nosebleeds, and uncontrolled bleeding (www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/spb/mnpages/dispages/cchf.htm).

CCHFV, belonging to the genus Nairovirus, circulates in an enzootic tick-vertebrate-tick cycle in which ticks can act as vectors and reservoirs. CCHFV has been found in ticks of >30 species; Hyalomma marginatum ticks are considered the most common vectors. Birds are the main hosts for the immature stages of this tick species (2). Viremia does not develop in most passerine birds (3,4), which are not able to pass the virus to ticks. However, migratory species could carry infected ticks over long distances and thereby disseminate the virus (2).

Since the first descriptions of human infections with this virus in 1944–1955 in Crimea, outbreaks of CCHF have been reported in Africa, Asia, and eastern Europe (1). Only imported cases have been reported in western Europe, although the causal agent has been amplified in H. lusitanicum ticks collected from deer in Spain (southwestern Europe) (5). This finding could be explained by the arrival of infected ticks transported by migratory birds coming from Africa (5). To confirm this hypothesis, we investigated the presence of CCHFV in ticks collected from migratory birds in northern Africa.

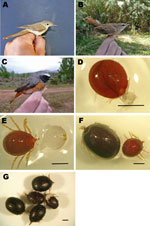

In April 2011, bird bandings were conducted in Zouala, Morocco (31°47′N, 4°14′W) (Figure 1). A total of 546 captured birds were checked for ticks, and parasites were found on 21 birds from 5 passerine bird species (Phoenicurus phoenicurus, Erythropygia galactotes, Iduna opaca, Acrocephalus scirpaceus, and I. pallida). All but I. pallida birds are passerine trans-Saharan migrant species, coming from central and southern Africa and able to reach the Iberian Peninsula.

A total of 52 ticks (19 larvae and 33 nymphs) were processed. Genomic DNA and total RNA from ticks were individually purified by using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA extracts were used as templates for 16S rDNA PCR assays (6), and all specimens were classified as H. marginatum ticks. RNA was retrotranscribed by using the Omniscript RT kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA extracts were distributed in 6 pools used as templates for 2 nested PCRs with Eecf and Gre primer pairs (7) (Table). Negative controls (with template DNA but without primers and with primers and containing water instead of template DNA) were included in all assays.

Nested PCR assays using Eecf primers were positive for 4/6 pools; all samples were negative by Gre PCR primers (7). Three of 4 amplicons (associated with P. phoenicurus, E. galactotes, and I. opaca bird species; Figure 2) could be sequenced, and nucleotide sequences were compared with those available in GenBank by using BLAST (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/Blast.cgi). All nucleotide sequences were identical and showed 100% identity with the Sudan AB1-2009 and Mauritania ArD39554 CCHFV strains (GenBank accession nos. HQ378179 and DQ211641) and 98.9% identity with the sequence amplified from ticks from Spain (5).

The detection of CCHFV in ticks from migratory birds in Zouala demonstrates the circulation of this virus in Morocco. This country has optimal conditions for the establishment of CCHF, including populations of H. marginatum ticks and reservoirs of the virus, such as livestock. Furthermore, autochthonous cases of the disease have been reported in neighboring Mauritania (8).

Our finding of 3 positive tick pools demonstrates the potential dispersion of the virus through infected ticks transported by migratory birds. Several bird species, including P. phoenicurus, E. galactotes, I. opaca, and A. scirpaceus, migrate in the spring from southern or central Africa to northern Europe. The Iberian Peninsula may be a stopover or breeding site along those routes (9), which suggests that migratory birds may transport H. marginatum ticks from Africa to Europe (2).

Ticks of this species are found in Africa, southern Asia, and southern Europe (10,11); some specimens have been collected in northern European regions such as Germany or England (12,13). Birds are commonly parasitized by immature stages of H. marginatum, a 2-host tick that has the same host for larva and nymph stages. Thus, ticks may be attached to the bird for >2–3 weeks (11). An average ground speed of 50 km/h for migratory birds crossing Sahara has been reported (14); this speed would enable birds to cover the distance between Morocco and the Iberian Peninsula in less time than it would take ticks to develop from immature to adult.

In early May 2012, our team captured A. scirpaceus birds parasitized by H. marginatum ticks in northern Spain (42°48′N; 2°39′W); some ticks were fully engorged nymphs (A.M. Palomar, unpub. data). A high probability exists that the larvae were attached to birds in Africa and molted and engorged during migration, which supports the possibility of the arrival of migratory birds with CCHFV-infected ticks.

A study conducted in England of CCHFV in ticks collected from migratory birds found negative real-time PCR results for CCHFV, although the parasitization rate of birds with H. marginatum ticks was low (13). In addition, a group of experts has reported that migratory birds may not be sufficient to establish new foci of CCHFV infection in Europe and may not represent a high risk for its implantation because adult ticks are necessary and immature specimens cannot find optimal climate conditions to molt in spring (10). However, this report stated that Spain’s average spring temperatures are lower than those needed for birds to molt; in April 2011, the weather station located in northern Spain (La Rioja) (42°27′N, 2°19′W) recorded average temperatures >14°C for 20/30 days. In addition, H. marginatum tick populations are established on the Iberian Peninsula.

The finding of fragments of the small segment of CCHFV identical to fragments of the Mauritania and Sudan strains and closely related to the sequence previously amplified by our team (5), in pools of immature specimens of different engorged states (Figure 2), may explain 2 hypotheses. First, infected ticks from CCHF-endemic areas, such as Mauritania or Sudan, could have attached to birds and transported to Morocco over them. Second, these ticks could have been carried from Africa to the Iberian Peninsula, thus explaining the circulation of CCHFV in southwestern Europe.

Autochthonous cases of CCHF have not been reported in southwestern Europe, and CCHFV has not been detected in ticks from migratory birds in Europe (13). However, some authors support the limited role of migratory birds harboring CCHFV-infected ticks for the establishment of the virus (10,15). Nevertheless, the finding of CCHFV from migratory birds in Morocco, along with the previous detection of the virus in Spain (5), where H. marginatum tick populations and CCHFV reservoirs occur, call for further study of the distribution of CCHFV in southwestern Europe. Health care workers should be informed about the possibility of CCHF and the clinical picture in the potential disease-endemic areas, and groups potentially at risk for infection (e.g., health care workers, hunters, farmers) and reservoirs for the virus (livestock) should be investigated further.

Dr Palomar has worked in the Center of Rickettsioses and Arthropod-borne Diseases at the Infectious Diseases Area, Hospital San Pedro–Center for Biomedical Research of La Rioja since March 2009. Her research interests are the taxonomy of ticks and their associated pathogens.

Acknowledgment

Fundación Rioja Salud awarded a grant (FRS/PIF-01/10) to A.M.P. Financial support was provided in part by a grant from “Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Spain” (PS09/02492).

References

- Ergonul O. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus: new outbreaks, new discoveries. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2:215–20.

- Hoogstraal H, Kaiser MN, Traylor MA, Gaber S, Guindy E. Ticks (Ixodidea) on birds migrating from Africa to Europe and Asia. Bull World Health Organ. 1961;24:197–212.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Shepherd AJ, Swanepoel R, Leman PA, Shepherd SP. Field and laboratory investigation of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus (Nairovirus, family Bunyaviridae) infection in birds. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987;81:1004–7.. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zeller HG, Cornet JP, Camicas JL. Experimental transmission of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus by west African wild ground-feeding birds to Hyalomma marginatum rufipes ticks. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:676–81.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Estrada-Peña A, Palomar AM, Santibáñez P, Sánchez N, Habela MA, Portillo A, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in ticks, southwestern Europe, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:179–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Black WC, Piesman J. Phylogeny of hard and soft tick taxa (Acari:Ixodida) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10034–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Midilli K, Gargili A, Ergonul O, Elevli M, Ergin S, Turan N, The first clinical case due to AP92 like strain of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus and a field survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:90. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nabeth P, Cheikh DO, Lo B, Faye O, Vall IO, Niang M, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Mauritania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:2143–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hoyo J, Elliot A, Christie DA. Handbook of the birds of the world, vol. 10–11. Barcelona (Spain): Lynx Edicions; 2004.

- European Food Safety Authority Panel on Animal Health and Welfare. Scientific opinion on the role of tick vectors in the epidemiology of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever and African swine fever in Eurasia. EFSA Journal. 2010;8:1703 [cited 2012 Jul 22]. http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/doc/1703.pdf

- Estrada-Peña A, Martínez M, Muñoz MJ. A population model to describe the distribution and seasonal dynamics of the tick Hyalomma marginatum in the Mediterranean basin. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2011;58:213–23.

- Rumer L, Graser E, Hillebrand T, Talaska T, Dautel H, Mediannikov O, Rickettsia aeschlimannii in Hyalomma marginatum ticks, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:325–6. .DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jameson LJ, Morgan PJ, Medlock JM, Watola G, Vaux AG. Importation of Hyalomma marginatum, vector of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus, into the United Kingdom by migratory birds. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012;3:95–9.

- Schmaljohann H, Liechti F, Bruderer B. Songbird migration across the Sahara: the non-stop hypothesis rejected! Proc Biol Sci. 2007;274:735–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gale P, Stephenson B, Brouwer A, Martinez M, de la Torre A, Bosch J, Impact of climate change on risk of incursion of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus in livestock in Europe through migratory birds. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;112:246–57. . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Table

Cite This Article1Data from this study were presented in part at the XVI Congreso de la Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica, Bilbao, Spain, May 9–11, 2012.

Table of Contents – Volume 19, Number 2—February 2013

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

José A. Oteo, Área de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital San Pedro–CIBIR, C/Piqueras 98-7ª NE, 26006 Logroño (La Rioja), Spain

Top