Volume 19, Number 3—March 2013

Letter

Reemerging Schmallenberg Virus Infections, Germany, 2012

To the Editor: In 2011, Schmallenberg virus, a novel orthobunyavirus of the Simbu serogroup, emerged in Germany and the Netherlands and spread rapidly over large parts of central and western Europe (1–5). The infection primarily affects ruminants but affects camelids as well (1,6). So far, evidence has not shown that humans are susceptible to Schmallenberg virus infection (7). Although the infection in adult animals causes only mild symptoms (1) or remains clinically inapparent, in pregnant animals, transplacental transmission during a limited period can lead to the birth of severely malformed progeny (1,2). Acute infections of adult ruminants or malformed Schmallenberg virus–positive offspring have been detected on >5,000 farms in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. Also, a high proportion of adult ruminants were seropositive for antigens of the virus in the core region affected by Schmallenberg virus in the Netherlands, Germany, and Belgium (2,4,5). Schmallenberg virus caused the first known outbreak of an infection with a virus of the Simbu serogroup in Europe. Schmallenberg virus infections are notifiable in Germany. Biting midges seem to play a key role in the transmission of the infection (8), and this transmission led to seasonal spread of the infection in summer and autumn 2011.

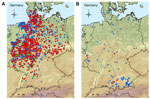

We report the recurrence of Schmallenberg virus infection in adult cattle, sheep, and a goat in Germany in 2012. Veterinary authorities at the county or town level report the animal holdings where laboratory-confirmed Schmallenberg virus infections are found to the central national database for notifiable animal diseases (Tierseuchennachrichtensystem), which is maintained by the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut; the reports are made online. This database was analyzed for reported holdings with Schmallenberg virus infections that had been detected in adult animals from June 1, 2002 through October 31, 2012, and confirmed by PCR (9) or virus isolation. In total, 82 infections were reported in adult cattle, 8 in adult sheep, and 1 in a goat (Figure). Forty-five of the cattle holdings and 4 sheep holdings submitted samples for testing because the affected animals had shown clinical signs. One case was detected in a sheep flock, and 5 cases were detected in cattle in trade examinations. For the remaining cases, no specific reason for testing was reported.

Although some cases were reported from the region in western and northern Germany where the epidemic had its center in 2011 (Figure, panel A), several new infections occurred in regions in southern Germany where no cases or only few cases of Schmallenberg virus infection had been detected before (Figure, panel B). This phenomenon may have occurred because of a high level of protective immunity at the population level in the region affected before transmission resumed in 2012, although a substantial proportion of the animals at the margin of the affected area remained susceptible. Schmallenberg virus that has overwintered in these areas may thus be transmitted to naive animals and has apparently spread to regions in southern Germany that were not affected or were less affected by the previous Schmallenberg virus epidemic. Schmallenberg virus could also be introduced into neighboring countries through infected arthropods. Although the respective reports may not have been formally published, indications were that Schmallenberg virus had spread at least to Austria, Ireland, Finland, Norway, Poland, Sweden, and Switzerland by summer/autumn 2012.

Schmallenberg virus infection is often mild or clinically inapparent in adult animals and leads only to a short viremic period of ≈4–5 days (1). Because a substantial proportion of new infections in adult animals are likely not recognized, the new cases reported in Germany starting in June 2012 probably represent only the so-called tip of the iceberg. Nevertheless, PCR analysis to detect Schmallenberg virus in samples from animals with clinical signs is a valuable method for identifying first cases in areas where Schmallenberg virus infections have not previously been found.

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the farmers, diagnosticians in the regional laboratories, and veterinary officials who provided data on reemerging Schmallenberg virus cases.

References

- Hoffmann B, Scheuch M, Höper D, Jungblut R, Holsteg M, Schirrmeier H, Novel orthobunyavirus in cattle, Europe, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:469–72. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Garigliany MM, Bayrou C, Kleijnen D, Cassart D, Desmecht D. Schmallenberg virus in domestic cattle, Belgium, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1512–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Muskens J, Smolenaars AJ, van der Poel WH, Mars MH, van Wuijckhuise L, Holzhauer M, [Diarrhea and loss of production on Dutch dairy farms caused by the Schmallenberg virus]. [in Dutch]. Tijdschr Diergeneeskd. 2012;137:112–5 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Elbers AR, Loeffen WL, Quak S, de Boer-Luijtze E, van der Spek AN, Bouwstra R, Seroprevalence of Schmallenberg virus antibodies among dairy cattle, the Netherlands, winter 2011–2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1065–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- European Food Safety Authority. “Schmallenberg” virus: analysis of the epidemiological data and impact assessment. EFSA Journal. 2012;10: 2768. . www.efsa.europa.eu.efsajournal.DOIGoogle Scholar

- World Organisation for Animal Health. OIE technical factsheet, May 2012 [cited 2013 Jan 3]. 1. Schmallenberg virus. www.oie.int/.../A_Schmallenberg_virus.pdf

- Ducomble T, Wilking H, Stark K, Takla A, Askar M, Schaade L, Lack of evidence for Schmallenberg virus infection in highly exposed persons, Germany, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1333–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rasmussen LD, Kristensen B, Kirkeby C, Rasmussen TB, Belsham GJ, Bødker R, Culicoids as vectors of Schmallenberg virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1204–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bilk S, Schulze C, Fischer M, Beer M, Hlinak A, Hoffmann B. Organ distribution of Schmallenberg virus RNA in malformed newborns. Vet Microbiol. 2012;159:236–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Cite This ArticleRelated Links

Table of Contents – Volume 19, Number 3—March 2013

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Franz J. Conraths, Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Federal Research Institute for Animal Health–Institute of Epidemiology, Seestrasse 55, Wusterhausen 16868, Germany

Top