Volume 19, Number 8—August 2013

Dispatch

Travel-associated Diseases, Indian Ocean Islands, 1997–2010

Abstract

Data collected by the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network for 1,415 ill travelers returning from Indian Ocean islands during 1997–2010 were analyzed. Malaria (from Comoros and Madagascar), acute nonparasitic diarrhea, and parasitoses were the most frequently diagnosed infectious diseases. An increase in arboviral diseases reflected the 2005 outbreak of chikungunya fever.

The outbreak of chikungunya fever in Indian Ocean islands (IOI) provides new insights on emerging infections in this geographic region (1). We present data collected over 14 years from travelers to IOI who visited GeoSentinel clinics.

GeoSentinel sites are specialized travel clinics providing surveillance data for ill travelers. Detailed methods for recruitment of patients for the GeoSentinel database are described elsewhere (2). Demographics, travel characteristics, and individual medical data were obtained from travelers to Comoros (including Mayotte), Madagascar, Maldives, Mauritius, Réunion Island, and Seychelles during March 1, 1997–December 31, 2010. Statistical significance was determined by using Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for quantitative variables. A 2-sided significance level of p<0.05 was considered significant.

This study comprised 1,415 ill patients (Table 1). Demographic data varied according to the visited island. Median age was 36 years, and the male to female ratio was 1.1:1.0. The most common reason for travel was tourism (44.5%), followed by visiting friends and relatives (VFR) (30.8%). Only 43.0% of travelers had a pre-travel encounter with a travel medicine specialist or general practitioner.

Illness patterns varied by place of exposure (Figure 1). Malaria, the most frequently diagnosed illness (388 [27.4%] travelers), accounted for 74.1% of diagnoses for VFR but only 6.6% for non-VFR travelers (p<0.01). Plasmodium falciparum malaria represented 88.0% of cases, including 12 cases of severe malaria, mostly from Comoros or Madagascar. One case of P. ovale malaria was reported from Mauritius in a person who had previously traveled to Cameroon.

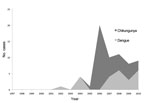

Arboviral disease diagnoses included 40 cases of chikungunya and 24 cases of dengue. Overall, arboviral diseases accounted for 4.5% of the total diagnoses. Arboviral diseases accounted for 36.0% of diseases acquired by travelers to Réunion Island (vs. 3.6% in non–Réunion Island travelers, p<0.01) and were more frequent in tourists than in nontourists (6.5% vs. 2.9%, p<0.01). Numbers of arboviral diseases showed a sustained increase and peaked in 2006. Dengue was noted only after 2001. Chikungunya cases dramatically increased in 2006 and were sustained at a lower level during 2007–2010, suggesting local transformation from epidemic to endemic phases or better notification of the diagnosis (Figure 2).

Parasitic infections other than malaria accounted for 131 (9.3%) diagnoses. A higher proportion of parasitoses occurred in travelers to Madagascar than in persons who had not traveled there (21.3% vs. 2.6%, p<0.01) and in missionary than non-missionary travelers (18.7% vs. 7.9%, p<0.01). Intestinal helminths or protozoans were the most commonly identified parasites. Schistosomiasis (21 cases) was reported from Madagascar only.

Acute nonparasitic diarrhea accounted for 162 (11.5%) final diagnoses. Higher proportions of such diarrhea occurred in travelers to Madagascar than in persons who had not traveled there (15.7% vs. 9.1%, p<0.01) and in travelers to Maldives than in persons who had not traveled there (18.4% vs. 10.5%, p<0.01). In 23 (14.2%) cases, a pathogen was identified. Acute nonparasitic diarrhea and skin infections were more frequently reported in tourists than in nontourists (17.3% and 12.4% vs. 6.8% and 3.8%, respectively [p<0.01]). The proportion of respiratory infections was higher in persons traveling for business than in persons traveling for other reasons (11.2% vs. 5.1%, p<0.01).

Mosquito bites, food and water consumption, and direct contact with skin were the most frequent modes of disease transmission (Table 2). The proportion of mosquito-transmitted diseases was higher among travelers to Comoros than among other travelers (80.2% vs. 10.0%, p = 0.006). The proportion of foodborne diseases was higher among travelers to Madagascar than in travelers to other areas (27.5% vs. 10.9%, p<0.001) and to Maldives than to other areas (23.0% vs. 15.8%, p = 0.03). Diseases transmitted through skin contact accounted for a higher proportion of diagnoses in travelers returning from Madagascar than from other areas (18.1% vs. 7.6%, p<0.001). Compared with nonbusiness travelers, business travelers had a higher proportion of respiratory-transmitted diseases (1.9% vs. 12.3%, p<0.001) and sexually and blood-transmitted diseases (0.3% vs. 6.6%, p = 0.03).

This large study addresses travel-associated diseases in travelers returning from IOI. P. falciparum infection was the most common reason for seeking post-travel care, notably when returning from Comoros, a well-known malaria-endemic archipelago (3). Imported malaria is frequently described in France, particularly in Marseille, which is the preferred residence city for migrants from Comoros and their descendants (4). Previous reports have shown that VFR sought pre-travel advice less frequently than did other travelers, possibly because of economic concerns, language barriers, or cultural beliefs (5–7). We observed a lower proportion of malaria in persons who had traveled to Madagascar, where both P. falciparum and P. vivax are endemic, and only 1 case in a traveler to Mauritius, where few cases are reported (3). No malaria cases were identified from Réunion Island, Seychelles, or Maldives, which is consistent with travel medicine guidelines that do not recommend chemoprophylaxis for travelers visiting these islands (8).

The reports of dengue and chikungunya fever from all islands reflect the wide distribution of the vector, Aedes spp. mosquitoes. Our results parallel those of the chikungunya fever outbreak that spread throughout IOI during 2005–2006 (9), facilitated by an adaptive virus mutation that led to increased infectivity, replication, and transmission by A. albopictus mosquitoes (10). The outbreak affected hundreds of travelers to IOI (11). Concern about the possible spread of chikungunya fever increased with the autochthonous outbreak of chikungunya fever in Italy in 2007 that developed from a patient returning from India (12). This sporadic case confirmed the ability of the virus to settle in countries colonized by Aedes sp. mosquitoes as a result of increasing intercontinental exchanges. Surveillance of travelers with a view toward early diagnosis is a key element in controlling outbreaks of imported arboviral diseases.

Parasitic infections, including schistosomiasis, accounted for a major proportion of final diagnoses in travelers to Madagascar, where these infections represent a public health concern (13). Testing for such diseases should be considered in ill travelers returning from this island.

Nonparasitic diarrhea was reported mainly in tourists returning from Madagascar and the Maldives. Few pathogens were documented, reflecting the practice of empiric antimicrobial treatment before laboratory testing (14). The higher incidence of diarrheal illness among tourists could be explained by an immature mucosal immunity (15) and easier access to medical care.

Business travelers had a higher proportion of respiratory diseases, independent of the island visited. This finding may relate to longer stays in air conditioned hotels and close human-to-human contact in this population.

These data have at least 4 limitations. First, we included only returning travelers who were ill and receiving care at GeoSentinel sites. Second, self-limited diseases or diseases of short duration may be underrepresented. Third, the lack of a denominator does not permit calculation of prevalence. Fourth, diseases with very short or very long incubation periods might not, with certainty, be attributed to any particular destination. Nevertheless, our study describes the spectrum of diseases among travelers returning from each IOI based on robust numbers of ill travelers.

Ill travelers returning from IOI are heterogeneous in their demographic and travel characteristics and display specific diseases that depend on the island and the travel reason. These findings reflect the different economic, ecologic, and public health situations found across this region (Technical Appendix Table). More than two thirds of diseases in travelers to IOI were, theoretically, preventable by reinforcing food and hand hygiene and by avoiding insect bites or direct contact with soil and fresh water. Most travelers in our survey traveled to a single island; thus, targeted destination-specific pre-travel advice and post-travel medical management of ill persons should be provided on a country-level basis rather than addressed nonspecifically.

Dr Savini is practitioner in the unit of infectious and tropical disease in the Department of Infectious Diseases, Laveran Military Teaching Hospital, Marseille, France. Her research interests include travel medicine, notably imported malaria.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Parola who initiated the project. We are also grateful to A. Plier, D. Freedman, the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network staff, special advisors, and the members of the data use and publication committee for helpful comments.

GeoSentinel (www.istm.org/geosentinel/main.html), the Global Surveillance Network of the International Society of Travel Medicine, is supported by Cooperative Agreement U50 CI000359 from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Simon F, Parola P, Grandadam M, Fourcade S, Oliver M, Brouqui P, Chikungunya infection: an emerging rheumatism among travelers returned from Indian Ocean islands. Report of 47 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:123–37 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE, Fisk T, Robins R, von Sonnenburg F, Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:119–30 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. World malaria report. 2010 [cited 2013 May 13]. http://www.who.int/malaria/World_malaria_report_2010/worldmalariareport2010.pdf.13

- Parola P, Gazin P, Pradines B, Parzy D, Delmont J, Brouqui P. Marseille: a surveillance site for malaria from the Comoros Islands. J Travel Med. 2004;11:184–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Leder K, Tong S, Weld L, Kain KC, Wilder-Smith A, von Sonnenburg F, Illness in travelers visiting friends and relatives: a review of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1185–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McCarthy M. Should visits to relatives carry a health warning? Lancet. 2001;357:862 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Casalino E, Le Bras J, Chaussin F, Fichelle A, Bouvet E. Predictive factors of malaria in travelers to areas where malaria is endemic. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1625–30. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. International travel and health. April 2012 [cited 2013 May 13]. http://www.who.int/ith/chapters/ith2012en_countrylist.pdf

- Josseran L, Paquet C, Zehgnoun A, Caillere N, Le Tertre A, Solet JL, Chikungunya disease outbreak, Réunion Island. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1994–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tsetsarkin KA, Vanlandingham DL, McGee CE, Higgs S. A single mutation in chikungunya virus affects vector specificity and epidemic potential. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e201. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: chikungunya fever diagnosed among international travelers—United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:276–7 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rezza G, Nicoletti L, Angelini R, Romi R, Finarelli AC, Panning M, Infection with chikungunya virus in Italy: an outbreak in a temperate region. Lancet. 2007;370:1840–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Institut Pasteur of Madagascar. Annual report. 2009 [cited 2013 May 13]. http://www.pasteur.mg/IMG/pdf/RAP2009_nouv.pdf

- Leggat PA, Goldsmid JM. Travelers' diarrhoea: health advice for travelers. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2004;2:17–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hoge CW, Shlim DR, Echeverria P, Rajah R, Herrmann JE, Cross JH. Epidemiology of diarrhea among expatriate residents living in a highly endemic environment. JAMA. 1996;275:533–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Cite This Article1Additional members of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network who contributed data are listed at the end of this article.

Table of Contents – Volume 19, Number 8—August 2013

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Hélène Savini, Service de Pathologie Infectieuse et Tropicale, Hôpital d'Instruction des Armées Laveran, 34 Boulevard Laveran BP 60149, 13384 Marseille Cedex 13, France

Top