Volume 21, Number 10—October 2015

Research

Environmental Factors Related to Fungal Wound Contamination after Combat Trauma in Afghanistan, 2009–2011

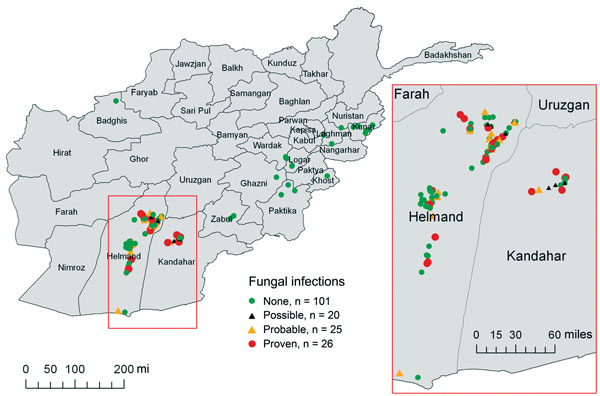

Figure 1

Figure 1. Geographic distribution of 71 case-patients with invasive fungal wound infections and 101 matched control-patients. Afghanistan, 2009–2011. Inset shows a detailed view of southern Afghanistan region where most cases originated. The IFI case-patients are classified according to established definitions (13). A proven IFI is confirmed by angioinvasive fungal elements on histopathologic examination. A probable IFI had fungal elements identified on histopathologic examination without angioinvasion. A possible IFI had wound tissue grow mold; however, histopathologic features were either negative for fungal elements or a specimen was not sent for evaluation. In addition, to be identified as an IFI, the wound must demonstrate recurrent necrosis after at least 2 surgical débridements. Because injuries frequently occurred in close proximity, some points overlay other points.

References

- Pfaller MA, Pappas PG, Wingard JR. Invasive fungal pathogens: current epidemiological trends. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S3–14. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Neblett Fanfair R, Benedict K, Bos J, Bennett SD, Lo Y-C, Adebanjo T, Necrotizing cutaneous mucormycosis after a tornado in Joplin, Missouri, in 2011. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2214–25. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634–53. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vitrat-Hincky V, Lebeau B, Bozonnet E, Falcon D, Pradel P, Faure O, Severe filamentous fungal infections after widespread tissue damage due to traumatic injury: six cases and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis. 2009;41:491–500 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hajdu S, Obradovic A, Presterl E, Vecsei V. Invasive mycoses following trauma. Injury. 2009;40:548–54. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Warkentien T, Rodriguez C, Lloyd B, Wells J, Weintrob A, Dunne J, Invasive mold infections following combat-related injuries. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1441–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lanternier F, Dannaoui E, Morizot G, Elie C, Garcia-Hermoso D, Huerre M, A global analysis of mucormycosis in France: the RetroZygo Study (2005–2007). Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(Suppl 1):S35–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Skiada A, Rigopoulos D, Larios G, Petrikkos G, Katsambas A. Global epidemiology of cutaneous zygomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:628–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:236–301. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Benedict K, Park BJ. Invasive fungal infections after natural disasters. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:349–55. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Radowsky JS, Strawn AA, Sherwood J, Braden A, Liston W. Invasive mucormycosis and aspergillosis in a healthy 22-year-old battle casualty: case report. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2011;12:397–400. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Paolino KM, Henry JA, Hospenthal DR, Wortmann GW, Hartzell JD. Invasive fungal infections following combat-related injury. Mil Med. 2012;177:681–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Weintrob AC, Weisbrod AB, Dunne JR, Rodriguez CJ, Malone D, Lloyd BA, Combat trauma-associated invasive fungal wound infections: epidemiology and clinical classification. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:214–24. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rodriguez CJ, Weintrob AC, Shah J, Malone D, Dunne JR, Weisbrod AB, Risk factors associated with invasive fungal Infections in combat trauma. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2014;15:521–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tribble DR, Conger NG, Fraser S, Gleeson TD, Wilkins K, Antonille T, Infection-associated clinical outcomes in hospitalized medical evacuees after traumatic injury: Trauma Infectious Disease Outcome Study. J Trauma. 2011;71(Suppl):S33–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Eastridge BJ, Jenkins D, Flaherty S, Schiller H, Holcomb JB. Trauma system development in a theater of war: experiences from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. J Trauma. 2006;61:1366–72. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Evriviades D, Jeffery S, Cubison T, Lawton G, Gill M, Mortiboy D. Shaping the military wound: issues surrounding the reconstruction of injured servicemen at the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366:219–30. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol. 2005;25:1965–78. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Phillips SJ, Anderson RP, Schapire RE. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol Modell. 2006;190:231–59. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Elith J, Graham CH, Anderson RP, Dudik M, Ferrier S, Guisan A, Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography. 2006;29:129–51. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Hernandez PA, Graham CH, Master LL, Albert DL. The effect of sample size and species characteristics on performance of different species distribution modeling methods. Ecography. 2006;29:773–85. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Swets JA. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science. 1988;240:1285–93 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fielding AH, Bell JF. A review of methods for the assessment of prediction errors in conservation presence/absence models. Environ Conserv. 1997;24:38–49. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Moffett A, Shackelford N, Sarkar S. Malaria in Africa: vector species' niche models and relative risk maps. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e824. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rouse JW, Haas RH, Schell JA, Deering DW. Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. In: Freden SC, Mercanti EP, Becker MA, editors. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Third Earth Resources Technology Satellite-1 Symposium. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 1974. p. 309–17.

- Lillesand TM, Kiefer RW, Chipman JW. Earth resources satellites operating in the optical spectrum. In: Remote sensing and image interpretation. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. p. 464.

- Richardson M. The ecology of the zygomycetes and its impact on environmental exposure. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15(Suppl 5):2–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Horn BW. Ecology and population biology of aflatoxigenic fungi in soil. J Toxicol Toxin Rev. 2003;22:351–79. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Collado J, Platas G, Gonzalez I, Pelaez F. Geographical and seasonal influences on the distribution of fungal endophytes in Quercus ilex. New Phytol. 1999;144:525–32. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Cotty PJ. Aflatoxin-producing potential of communities of Aspergillus section Flavi from cotton producing areas in the United States. Mycol Res. 1997;101:698–704. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Qu B, Li HP, Zhang JB, Xu YB, Huang T, Wu AB, Geographic distribution and genetic diversity of Fusarium graminearum and F. asiaticum on wheat spikes throughout China. Plant Pathol. 2008;57:15–24 .DOIGoogle Scholar

- Reis A, Boiteux LS. Alternaria species infecting Brassicaceae in the Brazilian neotropics: Geographical distribution, host range and specificity. J Plant Pathol. 2010;92:661–8 http://www.jstor.org/stable/41998855.

- Razzaghi-Abyaneh M, Shams-Ghahfarokhi M, Allameh A, Kazeroon-Shiri A, Ranjbar-Bahadori S, Mirzahoseini H, A survey on distribution of Aspergillus section Flavi in corn field soils in Iran: Population patterns based on aflatoxins, cyclopiazonic acid and sclerotia production. Mycopathologia. 2006;161:183–92. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Iftikhar S, Sultan A, Munir A, Iram S, Ahmad I. Fungi associated with rice-wheat cropping system in relation to zero and conventional tillage technologies. J Biol Sci. 2003;3:1076–83. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Milbrant A, Overend R. Assessment of biomass resources in Afghanistan. Golden (CO): National Renewable Energy Laboratory. 2011 [cited 2014 Oct 21]. http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy11osti/49358.pdf

- Khaliq A, Johnson K. As U.S. draws down, Afghan opium production thrives. Navy Times. May 1, 2014 [cited 2014 Oct 21]. http://www.navytimes.com/article/20140501/NEWS08/305010034/As-U-S-draws-down-Afghan-opium-production-thrives

1A portion of this material was presented at the Military Health System Research Symposium, August 18–21, 2014, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA.