Volume 22, Number 3—March 2016

CME ACTIVITY - Synopsis

Tuberculosis Caused by Mycobacterium africanum, United States, 2004–2013

Introduction

Medscape, LLC is pleased to provide online continuing medical education (CME) for this journal article, allowing clinicians the opportunity to earn CME credit.

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint providership of Medscape, LLC and Emerging Infectious Diseases. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)TM. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 75% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at http://www.medscape.org/journal/eid; (4) view/print certificate.

Release date: February 17, 2016; Expiration date: February 17, 2017

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will be able to:

• Distinguish the prevalence of Mycobacterium africanum tuberculosis in the United States

• Analyze the phylogenetics and epidemiology of M. africanum tuberculosis in the United States

• Compare the clinical characteristics of infection with M. africanum vs. M. tuberculosis

• Assess risk factors for M. africanum infection

CME Editor

Thomas J. Gryczan, MS, Technical Writer/Editor, Emerging Infectious Diseases. Disclosure: Thomas J. Gryczan, MS, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

CME Author

Charles P. Vega, MD, Clinical Professor of Family Medicine, University of California, Irvine. Disclosure: Charles P. Vega, MD, has disclosed the following financial relationships: served as an advisor or consultant for Allergan, Inc.; McNeil Consumer Healthcare; Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc.; served as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for Shire Pharmaceuticals.

Authors

Disclosures: Aditya Sharma, MD; Emily Bloss, PhD, MPH; Charles M. Heilig, PhD; and Eleanor S. Click, MD, PhD, have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Abstract

Mycobacterium africanum is endemic to West Africa and causes tuberculosis (TB). We reviewed reported cases of TB in the United States during 2004–2013 that had lineage assigned by genotype (spoligotype and mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit variable number tandem repeats). M. africanum caused 315 (0.4%) of 73,290 TB cases with lineage assigned by genotype. TB caused by M. africanum was associated more with persons from West Africa (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 253.8, 95% CI 59.9–1,076.1) and US-born black persons (aOR 5.7, 95% CI 1.2–25.9) than with US-born white persons. TB caused by M. africanum did not show differences in clinical characteristics when compared with TB caused by M. tuberculosis. Clustered cases defined as >2 cases in a county with identical 24-locus mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit genotypes, were less likely for M. africanum (aOR 0.1, 95% CI 0.1–0.4), which suggests that M. africanum is not commonly transmitted in the United States.

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by a group of highly-related organisms comprising the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC), which includes M. tuberculosis, M. africanum, and M. bovis. Although all members of MTBC might cause disease in humans, M. tuberculosis and M. africanum are the primary cause of disease in humans globally, whereas M. bovis primarily causes disease in cattle (1,2). Like M. tuberculosis, M. africanum is spread by aerosol transmission (3).

Phylogenetic analysis has suggested there are 7 major lineages of MTBC, designated L1–L7 (4,5). M africanum was traditionally identified by using biochemical methods. However, molecular methods have shown that M. africanum is composed of 2 distinct lineages: L5 (also known in other nomenclature systems as M. africanum West African 1 [MAF1], West African lineage I), which is genetically part of M. tuberculosis sensu stricto, and L6 (also known as M. africanum West African 2 [MAF2], West African lineage II), which is genetically more similar to M. bovis (4–9).

Among lineages that primarily infect humans, M. africanum lineages are considered phylogenetically more ancient relative to the modern lineages of M. tuberculosis (Euro-American, East African Indian, East Asian). M. africanum has been described as endemic to equatorial Africa, with specimens isolated from countries such as Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Senegal, Cameroon, Burkina Faso, The Gambia, Sierra Leone, and Uganda (8,10–21). M. africanum has also been isolated from patients with TB in countries in Europe (22–25), Brazil (26), and the United States (27). It is likely that TB caused by M. africanum in non-African countries is secondary to human migration from disease-endemic areas in equatorial Africa (25).

Several studies have explored whether there are clinical differences between TB caused by M. africanum and TB caused by M. tuberculosis. These studies demonstrated variable findings with regard to associations of M. africanum with HIV status and findings on chest radiography (8,28–30). Contacts of persons with TB caused by M. africanum appeared to have a lower rate of progression to active TB compared with contacts of persons with TB caused by M. tuberculosis, and a lower rate of genotype clustering has been described for M. africanum than for M. tuberculosis in relatively small studies from West Africa (14,29).

Although bacterial strains causing TB from all over the world can be found among cases of TB in the United States, analysis of routinely collected genotyping data for 2005–2009 showed that 179 (0.5%) of 36,458 TB cases reported nationally were caused by M. africanum (31). We sought to further expand knowledge of M. africanum in the United States by reviewing all cases of TB reported nationally during 2004–2013. The objectives of this study were to ascertain the proportion of TB cases caused by M. africanum in the United States; compare clinical and epidemiologic characteristics between M. africanum and M. tuberculosis; and determine the extent to which M. africanum strains in the United States might be related by transmission on the basis of genotype clustering.

Genotype data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Atlanta, GA, USA) National TB Genotyping Service for 2004 through 2013 were linked to routine demographic and clinical data from all culture-confirmed cases in the CDC National TB Surveillance System from all 50 US states and the District of Columbia (32). As described previously (33), phylogenetic lineage (M. africanum and M. tuberculosis) for TB cases was assigned on the basis of spoligotype by using a set of rules correlating spoligotype to lineages defined by large sequence polymorphisms; for cases that did not meet a full rule for assignment on the basis of spoligotype, 12-locus mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit variable number tandem repeats (MIRU-VNTRs) was used in addition to spoligotype to assign lineage. Cases reported during 2004–2008 only had 12-locus MIRU-VNTR data available, and cases reported during 2009–2013 had 24-locus MIRU-VNTR data available. To identify cases that could be caused by ongoing transmission in the United States, clusters of cases were defined as >2 cases with the same spoligotype and 24-locus MIRU-VNTR pattern in a given county. Cases that were caused by organisms other than M. africanum or M. tuberculosis were excluded from analysis.

All analyses were conducted by using R statistical software version 3.0.1 (R Core Group, Vienna, Austria). Statistical test results were considered significant at p<0.05. We examined patient attributes, genotype clustering, clinical characteristics (e.g., disease site), and social risk factors (e.g., homelessness) associated with M. africanum and M. tuberculosis. Odd ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were calculated. Differences in proportions of cases were detected by using Fisher exact and Pearson χ2 tests.

Factors identified as statistically significant by bivariable analysis at p<0.05 were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model to assess whether these factors were independently associated with M. africanum and M. tuberculosis. Tolerance <0.10 was used to detect co-linearity, and the likelihood ratio test was used to test for interaction. To address collinearity between race/ethnicity and origin of birth, variables for race/ethnicity, country of origin, and West African origin were combined into a single variable and included in selection of the multivariable regression model. West African origin was defined as having been born in any of the following countries in West Africa: Nigeria, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, The Gambia, Ghana, Mali, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, Cameroon, Mauritania, Niger, and Guinea-Bissau.

Ethics Statement

Data for this study were collected as part of routine TB surveillance by CDC. Thus, this study was not considered research involving human subjects, and institutional review board approval was not required.

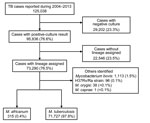

A total of 125,038 cases were reported to the National TB Surveillance System during 2004–2013 (Figure 1). Of these cases, 95,836 (76.6%) had a culture result positive for MTBC. Of cases with positive culture results, 73,290 (76.5%) had available lineage identification on the basis of genotype data. Of the cases for which lineage identification was available, the causative agent was determined to be M. africanum for 315 (0.4%) and M. tuberculosis for 71,727 (97.9%) cases: 1,248 (1.7%) cases had an isolated organism other than M. africanum or M. tuberculosis and were excluded from further analysis (Figure 1).

M. africanum was assigned as the causative agent of TB for isolates with a genotype-assigned lineage of L5 or L6. All isolates designated as M. africanum met the conventional spoligotype rule of the absence of spacers 8, 9, and 39 or the absence of spacers 7–9 and 39 (7). M. tuberculosis was assigned as the causative agent of TB for isolates with a genotype-assigned lineage of L1, L2, L3, L4, or L7.

Of the 315 case-patients with TB caused by M. africanum, 155 (49.2%) had the L5 lineage and 160 (50.8%) had the L6 lineage. Case-patients with the L5 lineage were most commonly born in Nigeria (n = 76), Liberia (n = 12), and Ghana (n = 12), and case-patients with the L6 lineage were most commonly born in Liberia (n = 27), Sierra Leone (n = 22), Guinea (n = 17), and The Gambia (n = 16).

Among case-patients with M. africanum as the causative agent of TB, 276 (87.6%) had country of birth other than the United States (Technical Appendix Table 1). Of the 276 foreign-born persons with M. africanum, most (254, 92.0%) persons were born in countries in West Africa, such as Nigeria (79, 31.1%), Liberia (39, 15.4%), and Sierra Leone (24, 9.4%).

Among all US states, 35 reported >1 case of TB caused by M. africanum (Figure 2). States that reported more than >10 cases of M. africanum TB during the study were New York (n = 77), Maryland (n = 41), Texas (n = 26), Virginia (n = 19), Georgia (n = 15), and California (n = 14). Across the United States, many reported cases of M. africanum TB appeared to be near major metropolitan areas, such as Atlanta, Georgia; Chicago, Illinois; Detroit, Michigan; Houston, Texas; Los Angeles, California; New York, New York; and Washington, DC.

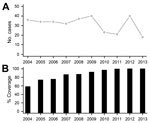

The annual number of reported TB cases identified with M. africanum in the United States during 2004–2013 ranged from 18 to 40 (median 34 annual cases) (Figure 3). During this period, the proportion of Mycobacterium spp. TB isolates from persons born in West Africa with culture-confirmed TB that were genotyped ranged from 68.0% to 97.1%, which was comparable with the overall proportion of culture-confirmed TB cases that were genotyped nationally.

On the basis of the genotype cluster definition of >2 cases in the same county with identical spoligotype and 24-locus MIRU-VNTR patterns, only 1 cluster of M. africanum cases was identified during 2009–2013. The cluster consisted of 2 case-patients with the L5 lineage: 1 foreign-born person and 1 US-born person.

Among 315 cases of M. africanum TB, 183 distinct genotypes were identified (spoligotype and 12-locus MIRU-VNTR available for cases reported during 2004–2013; Technical Appendix Table 2). Of these 183 genotypes, 139 (76.0%) were found in a single case only; the remaining 44 (24.0%) caused 176 cases. Among 141 M. africanum cases reported during 2009–2013 with spoligotype and 24-locus MIRU-VNTR data available, 123 distinct genotypes were identified (Technical Appendix Table 3). Of these 123 genotypes, 113 (91.9%) were found in isolates from 1 case only, and 10 (8.1%) were found in >1 case.

Bivariable analysis showed that M. africanum and M. tuberculosis TB cases had major differences for several characteristics (Technical Appendix Table 1). When compared with M. tuberculosis TB cases, M. africanum TB cases had higher odds of being in foreign-born persons (odds ratio [OR] 4.8, 95% CI 3.4–6.7), being in non-Hispanic black or multiracial non-Hispanic persons (OR 27.0, 95% CI 17.1–42.5), originating from countries in West Africa (OR 318.4, 95% CI 239.0–424.2), being in persons positive for HIV (OR 2.8, 95% CI 2.0–3.7), and being in persons with only extrapulmonary disease (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.4–2.4) or in persons with pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1–2.2).

M. africanum TB cases had lower odds than M. tuberculosis TB cases of being in a cluster (defined by spoligotype and 24-locus MIRU) of cases (OR 0.1, 95% CI 0.1–0.2), being in persons >65 years of age (OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1–0.5), being in persons with an abnormal chest radiographic result and cavitation (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.5–0.9) and in persons without cavitation (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.4–0.7), being in a resident of a correctional facility (OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.0–0.6), being in a homeless person (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–0.8), being in persons reporting excessive drug (OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1–0.5) or alcohol use (OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1–0.4), and being in persons who died during treatment (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.2–0.7). Among foreign-born persons, M. africanum TB cases had lower odds than M. tuberculosis TB cases of being in persons who had been in the United States for >5 years before reporting TB (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.3–0.5).

Multivariable analysis restricted to cases reported during 2009–2013 that had 24-locus MIRU-VNTR data available showed that foreign-born West African origin (OR 253.8, 95% CI 59.9–1076.1) and US-born non−Hispanic black race (OR 5.7, 95% CI 1.2–25.9) were independently associated with TB caused by M. africanum but not with TB caused by M. tuberculosis (Table). Clustered cases (OR 0.1, 95% CI 0.1–0.4) had lower adjusted odds of TB caused by M. africanum than TB caused by M. tuberculosis. Other risk factors were not independently associated with M. africanum versus M. tuberculosis. No significant interaction terms were identified.

To control for possible host differences in larger analysis, we conducted a subanalysis of cases among foreign-born persons from West Africa. In this subanalysis, clustering was the only significant variable at the bivariable level, and M. africanum TB cases had lower odds of being in a cluster of cases than M. tuberculosis TB cases (OR 0.1, 95% CI 0.1–0.9). Among foreign-born persons with West African origin, we found no significant differences in clinical characteristics (e.g., HIV status, cavitary disease, sputum smear results) between TB cases caused by M. africanum versus those caused by M. tuberculosis. M. africanum TB cases with L5 and L6 lineages had similar proportions of HIV positivity (18.1% vs. 17.5%; p = 0.9) and cavitary disease by chest radiography (25.4% vs. 42.5%; p = 0.051). We found no significant differences in clinical characteristics or social risk factors for TB caused by L5 or L6 lineages.

This study used nationally reported data on TB cases linked to genotype data to describe the epidemiology of M. africanum in the United States. The findings from this analysis indicate that M. africanum is a rare cause of TB in the United States and represents 315 (0.4%) of 73,290 cases with available genotype data reported during 2004–2013. Most cases were identified in large metropolitan areas throughout the United States. Although M. africanum is an infrequent cause of TB, most states reported >1 case of TB caused by M. africanum during the study period, which suggested that M. africanum is broadly distributed.

In this study, TB caused by M. africanum was more likely to occur in foreign-born West Africans and US-born non-Hispanic blacks and less likely in foreign-born persons originating from countries not in West Africa. These associations suggest that the epidemiology of M. africanum in the United States is driven primarily by migration of persons from West Africa. We also identified cases of M. africanum in US-born persons, primarily in non-Hispanic blacks. This finding suggests that transmission of M. africanum might occur in the United States, but the possibility of acquisition of TB during travel (e.g., to West Africa) cannot be excluded because travel history was not available in national surveillance data. In an initial report of 5 M. africanum cases in the United States, several case-patients did not report a history of travel to West Africa (34).

The low proportion of TB cases attributed to M. africanum suggests decreased transmissibility in the United States. Reasons for decreased transmission of M. africanum are unknown but could include decreased infectiousness or decreased progression to disease compared with M. tuberculosis, as was previously reported (8).

Our findings support the observation that M. africanum is highly restricted to West Africa, where it has been estimated to cause up to 50% of all TB cases, although the reason for this restriction remains unclear (8). A recent study from Ghana reported an association between M. africanum and patient ethnicity, which suggests specificity of host−pathogen interaction could be 1 factor in limiting the spread of M. africanum to West Africa (35).

Most M. africanum TB cases were not part of genotype clusters, which suggested that transmission of M. africanum in the United States is not common. M. africanum TB cases were less likely to be associated with genotype clustering than M. tuberculosis TB cases by analyses of all cases reported in the United States and in a subanalysis of persons born in West Africa. This lower association of clustering is consistent with investigations from Ghana and The Gambia, which found M. africanum less likely to be in spoligotype-defined clusters (30,36).

After controlling for other factors, we found that TB cases in the United States caused by M. africanum and M. tuberculosis were similar regarding clinical presentation, social risk factors, and treatment outcomes. These findings are consistent with those of studies that compared treatment outcomes among cases of M. africanum and M. tuberculosis TB in West Africa, but contrast with studies describing differential associations with HIV and chest radiography findings (8,14,28,29). Unlike several reported studies, we could not compare specific chest radiographic findings for M. africanum versus M. tuberculosis because detailed radiographic information is not available in US surveillance data (8). Our study demonstrated similar clinical characteristics of TB caused by L5 and L6 lineages of M. africanum, which is consistent with that of a previous report (29).

Our results should be interpreted in light of the incomplete availability of genotype data. Nationwide coverage of genotyping has increased over time (37), but genotype data were not available for all culture confirmed cases. Although it is possible that our study underestimates the true burden of M. africanum, we expect that changes in system coverage do not substantially affect the main findings of the study. In addition, M. africanum and M. tuberculosis were identified by spoligotype and MIRU-VNTR, rather than by more phylogenetically robust methods, such as large-sequence polymorphism analysis. Therefore, some misclassification might have occurred, but there is no reason to assume any bias was introduced. Finally, our definition of clustered cases was based solely on identical spoligotype and 24-locus MIRU-VNTR in the same county during 2009–2013 and therefore probably overestimates the extent of transmission that might be occurring at the county level. More robust methods for identifying clustered cases rely on a narrower time interval between cases and evidence of epidemiologic links between cases (38). Even with the direction of bias toward overestimation of clustering, we found only 1 cluster.

Although the annual number of reported TB cases in the United States has decreased in the past decade, the proportion of TB contributed by foreign-born persons has increased to >60% in recent years (39). Similar to this trend, TB caused by M. africanum is highest among foreign-born persons, which is consistent with the understanding that spread of M. africanum in countries outside Africa is driven by human migration from West Africa. Given the low burden of TB caused by M. africanum in the United States, the similarity in clinical features of TB caused by M. africanum and M. tuberculosis, and the lower odds of clustered cases of M. africanum than those of M. tuberculosis, routine reporting of TB caused by M. africanum above standard reporting for general TB does not appear warranted at this time.

Dr. Sharma is an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer at the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia. His primary interests are the epidemiology and control of infectious diseases, including TB, and drug-resistant bacteria.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lauren Cowan, James Posey, Anne Marie France, Benjamin Silk, and Thomas Navin for their assistance with genotype and surveillance data and partners at state and local public health departments for data collection.

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Thorel MF. Isolation of Mycobacterium africanum from monkeys. Tubercle. 1980;61:101–4 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Alfredsen S, Saxegaard F. An outbreak of tuberculosis in pigs and cattle caused by Mycobacterium africanum. Vet Rec. 1992;131:51–3 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- de Jong BC, Hill PC, Brookes RH, Gagneux S, Jeffries DJ, Otu JK, Mycobacterium africanum elicits an attenuated T cell response to early secreted antigenic target, 6 kDa, in patients with tuberculosis and their household contacts. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1279–86. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Comas I, Chakravartti J, Small PM, Galagan J, Niemann S, Kremer K, Human T cell epitopes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are evolutionarily hyperconserved. Nat Genet. 2010;42:498–503. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Firdessa R, Berg S, Hailu E, Schelling E, Gumi B, Erenso G, Mycobacterial lineages causing pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis, Ethiopia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:460–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hershberg R, Lipatov M, Small PM, Sheffer H, Niemann S, Homolka S, High functional diversity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis driven by genetic drift and human demography. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e311. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vasconcellos SE, Huard RC, Niemann S, Kremer K, Santos AR, Suffys PN, Distinct genotypic profiles of the two major clades of Mycobacterium africanum. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- de Jong BC, Antonio M, Gagneux S. Mycobacterium africanum: review of an important cause of human tuberculosis in West Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e744. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gagneux S, Small PM. Global phylogeography of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and implications for tuberculosis product development. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:328–37. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Frothingham R, Strickland PL, Bretzel G, Ramaswamy S, Musser JM, Williams DL. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Mycobacterium africanum isolates from West Africa. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1921–6 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Niemann S, Rusch-Gerdes S, Joloba ML, Whalen CC, Guwatudde D, Ellner JJ, Mycobacterium africanum subtype II is associated with two distinct genotypes and is a major cause of human tuberculosis in Kampala, Uganda. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3398–405. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sola C, Rastogi N, Gutierrez MC, Vincent V, Brosch R, Parsons L. Is Mycobacterium africanum subtype II (Uganda I and Uganda II) a genetically well-defined subspecies of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex? J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1345–6, author reply 6–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cadmus S, Palmer S, Okker M, Dale J, Gover K, Smith N, Molecular analysis of human and bovine tubercle bacilli from a local setting in Nigeria. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:29–34. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- de Jong BC, Hill PC, Aiken A, Awine T, Antonio M, Adetifa IM, Progression to active tuberculosis, but not transmission, varies by Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineage in The Gambia. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1037–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cadmus SI, Yakubu MK, Magaji AA, Jenkins AO, van Soolingen D. Mycobacterium bovis, but also M. africanum present in raw milk of pastoral cattle in north-central Nigeria. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2010;42:1047–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gomgnimbou MK, Refregier G, Diagbouga SP, Adama S, Kabore A, Ouiminga A, Spoligotyping of Mycobacterium africanum, Burkina Faso. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:117–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lawson L, Zhang J, Gomgnimbou MK, Abdurrahman ST, Le Moullec S, Mohamed F, A molecular epidemiological and genetic diversity study of tuberculosis in Ibadan, Nnewi and Abuja, Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38409. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Aliyu G, El-Kamary SS, Abimiku A, Brown C, Tracy K, Hungerford L, Prevalence of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections among tuberculosis suspects in Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e63170. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gehre F, Antonio M, Faihun F, Odoun M, Uwizeye C, de Rijk P, The first phylogeographic population structure and analysis of transmission dynamics of M. africanum West African 1—combining molecular data from Benin, Nigeria and Sierra Leone. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e77000. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gehre F, Antonio M, Otu JK, Sallah N, Secka O, Faal T, Immunogenic Mycobacterium africanum strains associated with ongoing transmission in The Gambia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1598–604. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kuaban C, Um Boock A, Noeske J, Bekang F, Eyangoh S. Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains and drug susceptibility in a cattle-rearing region of Cameroon. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18:34–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lari N, Rindi L, Bonanni D, Rastogi N, Sola C, Tortoli E, Three-year longitudinal study of genotypes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Tuscany, Italy. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1851–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Grange JM, Yates MD. Incidence and nature of human tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium africanum in South-East England: 1977–87. Epidemiol Infect. 1989;103:127–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jungbluth H, Fink H, Reusch F. Tuberculous infection caused by Myco. africanum in black africans resident in the German Federal Republic (author’s transl) [in German]. Prax Klin Pneumol. 1978;32:306–9 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Isea-Peña MC, Brezmes-Valdivieso MF, Gonzalez-Velasco MC, Lezcano-Carrera MA, Lopez-Urrutia-Lorente L, Martin-Casabona N, Mycobacterium africanum, an emerging disease in high-income countries? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:1400–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gomes HM, Elias AR, Oelemann MA, Pereira MA, Montes FF, Marsico AG, Spoligotypes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates from patients residents of 11 states of Brazil. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:649–56 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Desmond E, Ahmed AT, Probert WS, Ely J, Jang Y, Sanders CA, Mycobacterium africanum cases, California. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:921–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- de Jong BC, Adetifa I, Walther B, Hill PC, Antonio M, Ota M, Differences between TB cases infected with M. africanum, West-African type 2, relative to Euro-American M. tuberculosis: an update. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010;58:102–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Meyer CG, Scarisbrick G, Niemann S, Browne EN, Chinbuah MA, Gyapong J, Pulmonary tuberculosis: virulence of Mycobacterium africanum and relevance in HIV co-infection. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2008;88:482–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- de Jong BC, Hill PC, Aiken A, Jeffries DJ, Onipede A, Small PM, Clinical presentation and outcome of tuberculosis patients infected by M. africanum versus M. tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:450–6 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Moonan PK, Ghosh S, Oeltmann JE, Kammerer JS, Cowan LS, Navin TR. Using genotyping and geospatial scanning to estimate recent Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:458–65. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2012. Atlanta: The Centers; 2013.

- Click ES, Moonan PK, Winston CA, Cowan LS, Oeltmann JE. Relationship between Mycobacterium tuberculosis phylogenetic lineage and clinical site of tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:211–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Desmond E, Ahmed AT, Probert WS, Ely J, Jang Y, Sanders CA, Mycobacterium africanum cases, California. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:921–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Asante-Poku A, Yeboah-Manu D, Otchere ID, Aboagye SY, Stucki D, Hattendorf J, Mycobacterium africanum is associated with patient ethnicity in Ghana. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e3370 and. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yeboah-Manu D, Asante-Poku A, Bodmer T, Stucki D, Koram K, Bonsu F, Genotypic diversity and drug susceptibility patterns among M. tuberculosis complex isolates from southwestern Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21906. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis genotyping—United States, 2004–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:723–5 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Moonan PK, Ghosh S, Oeltmann JE, Kammerer JS, Cowan LS, Navin TR. Using genotyping and geospatial scanning to estimate recent Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:458–65. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2013: Atlanta: The Centers.

Figures

Table

Follow Up

Earning CME Credit

To obtain credit, you should first read the journal article. After reading the article, you should be able to answer the following, related, multiple-choice questions. To complete the questions (with a minimum 75% passing score) and earn continuing medical education (CME) credit, please go to http://www.medscape.org/journal/eid. Credit cannot be obtained for tests completed on paper, although you may use the worksheet below to keep a record of your answers. You must be a registered user on Medscape.org. If you are not registered on Medscape.org, please click on the “Register” link on the right hand side of the website to register. Only one answer is correct for each question. Once you successfully answer all post-test questions you will be able to view and/or print your certificate. For questions regarding the content of this activity, contact the accredited provider, CME@medscape.net. For technical assistance, contact CME@webmd.net. American Medical Association’s Physician’s Recognition Award (AMA PRA) credits are accepted in the US as evidence of participation in CME activities. For further information on this award, please refer to http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/about-ama/awards/ama-physicians-recognition-award.page. The AMA has determined that physicians not licensed in the US who participate in this CME activity are eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Through agreements that the AMA has made with agencies in some countries, AMA PRA credit may be acceptable as evidence of participation in CME activities. If you are not licensed in the US, please complete the questions online, print the certificate and present it to your national medical association for review.

Article Title:

Tuberculosis Caused by Mycobacterium africanum, United States, 2004–2013

CME Questions

1. You are evaluating a 40-year-old man with a severe cough and weight loss for 3 months. Results on chest x-ray suggest that he has tuberculosis. What is the percentage of cases of clinical tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium africanum in the current study of patients in the United States?

A. 0.4%

B. 2.9%

C. 6.5%

D. 12.0%

2. What should you consider regarding the epidemiology and phylogenetics of M. africanum infection in the current study?

A. Nearly all cases were L5, and only a small percentage were L6

B. Approximately 30% of patients affected were born outside of the United States

C. Most cases were reported among farm workers in rural areas

D. Most cases were not part of clusters

3. After full adjustment for patient factors, which of the following descriptions was a clinical characteristic of patients with M. africanum infection compared with those with M. tuberculosis in the current study?

A. M. africanum was more common among patients with HIV infection

B. M. africanum was more commonly associated with extrapulmonary disease only

C. M. africanum was less likely to produce cavitary lesions on chest x-ray

D. M. africanum and M. tuberculosis had similar clinical presentations

4. Which of the following variables was a risk factor for M. africanum vs. M. tuberculosis infection in the current study?

A. Age 65 years or older

B. Homelessness

C. Excessive alcohol use

D. Black race

Activity Evaluation

|

1. The activity supported the learning objectives. |

||||

|

Strongly Disagree |

|

|

|

Strongly Agree |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

2. The material was organized clearly for learning to occur. |

||||

|

Strongly Disagree |

|

|

|

Strongly Agree |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

3. The content learned from this activity will impact my practice. |

||||

|

Strongly Disagree |

|

|

|

Strongly Agree |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

4. The activity was presented objectively and free of commercial bias. |

||||

|

Strongly Disagree |

|

|

|

Strongly Agree |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

Related Links

Table of Contents – Volume 22, Number 3—March 2016

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Aditya Sharma, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Rd NE, Mailstop E10, Atlanta, GA 30329-4027, USA

Top