Volume 22, Number 5—May 2016

Dispatch

Fatal Monocytic Ehrlichiosis in Woman, Mexico, 2013

Abstract

Human monocytic ehrlichiosis is a febrile illness caused by Ehrlichia chaffeensis, an intracellular bacterium transmitted by ticks. In Mexico, a case of E. chaffeensis infection in an immunocompetent 31-year-old woman without recognized tick bite was fatal. This diagnosis should be considered for patients with fever, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver enzyme levels.

Ehrlichia are rickettsia-like intracellular bacteria of human medical and veterinary importance. The first cases of human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) were described in 1987, and the etiologic agent was subsequently identified in the United States as Ehrlichia chaffeensis, a strictly intracellular bacterium belonging to the family Anaplasmataceae (1). E. chaffeensis is transmitted by Amblyomma americanum ticks; reservoirs include domestic and wild animals (2,3). In the United States, most cases occur from April through September. Ehrlichiosis is usually self-limiting with nonspecific symptoms similar to those of influenza: fever, malaise, headache, and myalgia. Leukopenia is found in 60%–70% of patients, thrombocytopenia in 60%, and mild to moderate elevation of serum transaminase levels in 80%–90% (4,5). Serologic evidence of infection may be absent during the early acute phase of illness. In patients with illness severe enough that they seek medical attention, 50% require hospitalization and 2%–3% die (6).

In Mexico, only 1 case of E. chaffeensis has been reported (7). Recently, E. chaffeensis has been identified in Rhipicephalus sanguineus and Amblyomma cajenennse ticks, which are found throughout Mexico (8). We report another case in Mexico, this one fatal.

In late August 2013, a previously healthy 31-year-old woman from Estado de Mexico, in central Mexico, was admitted to an emergency department with a history of fever for 15 days, chills, muscle aches, malaise, loss of appetite, and headache. She had worked in a marketplace selling fruit and vegetables; she had not traveled abroad in the previous 3 months and was not aware of having been bitten by a tick. At the time of physical examination, she was confused and had mild respiratory distress, hepatosplenomegaly, tachycardia, and blood pressure within reference range. Blood collected at the time of admission showed leukopenia (0.90 × 109 cells/L), neutropenia (0.31 × 109 cells/L), lymphocytopenia (0.59 × 109 cells/L), thrombocytopenia (76 × 109 platelets/L), anemia (hemoglobin 8.2 g/dL), and elevated serum concentrations of aspartate transaminase (2,748 IU/L) and alanine transaminase (350 IU/L). A full evaluation for sepsis (blood cultures, morphologic evaluation, and culture of bone marrow aspirate) was performed. The bone marrow aspirate contained no significant abnormalities. Computed tomography indicated hepatosplenomegaly and a small pericardial effusion; ultrasonography indicated bilateral nephromegaly; and echocardiography indicated a small pericardial effusion and an ejection fraction of 59%.

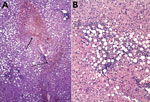

After these procedures were completed, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU); 1 day later, she was stable and discharged to a regular hospital ward, at which time blood and bone marrow culture results were negative. No morulae were detected in smears of peripheral blood and bone marrow. At that time, the patient’s mental status included confusion, a psychotic episode, and symptoms of anxiety; a psychiatrist prescribed benzodiazepines. Prednisone therapy was added for suspected hemophagocytic syndrome. The patient’s condition deteriorated; she experienced bleeding and hemodynamic instability and persistent fever. Four days after initial ICU discharge, she was transferred back to ICU, where she received antimicrobial drug therapy consisting of levofloxacin, amikacin, and meropenem and a transfusion of erythrocytes, plasma, and platelets. On her third day in the ICU, the patient still had pancytopenia and elevated concentrations of aspartate transaminase (674 IU/L) and alanine transaminase (105 IU/L). Blood, liver, and spleen samples were evaluated by PCR for Mycobacterium spp., Rickettsia spp., Ehrlichia spp., and Anaplasma phagocytophilum. E. chaffensis was found in the blood sample, and a morula-like structure was observed in a liver biopsy sample (Figure 1, panel C). Treatment with doxycycline (100 mg/12 h) was initiated; 2 days later her fever abated, but hypovolemic shock resulting from hemorrhage necessitated mechanical ventilatory assistance. On day 4 after initiation of doxycline, acute renal failure developed and hemodialysis was begun. On day 10, the patient experienced multisystemic failure with hemodynamic instability; despite inotropic support, she died.

Laboratory studies of a blood sample taken on the second day after the patient’s original admission to hospital revealed no antibodies against hepatitis A, B, C, or E; parvovirus B-19; or HIV. PCR for Mycobacterium spp. was negative. Histopathologic study of the liver showed centrilobular hepatic necrosis, macrovesicular steatosis, and lymphohistiocytic inflammation (Figure 1).

After death, the diagnosis of HME was confirmed by nested PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene from spleen and liver tissues, by use of primers previously described (8). Sequencing of the PCR products showed 99.8% homology with E. chaffeensis str. Arkansas (GenBank accession no. KT308164). PCR results for Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Rickettsia rickettsii were negative.

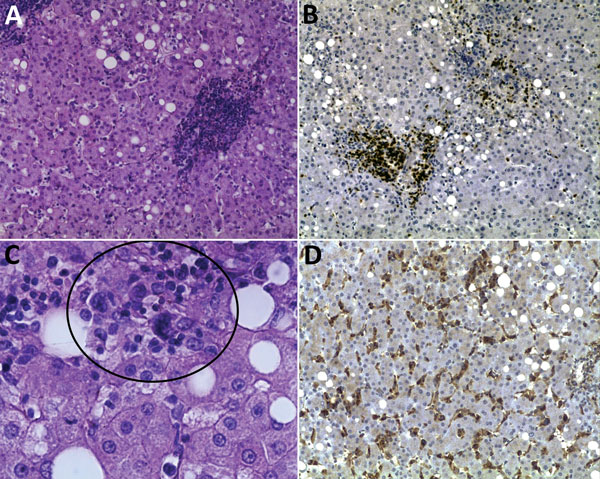

Blood, serum, liver, and spleen samples were transferred to the Rickettsial and Ehrlichial Research Laboratory, University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, TX, USA) where 2 fragments of the dsb gene were amplified from blood, liver, and spleen DNA by real-time PCR as previously described (9). The amplicons showed 100% homology with E. chaffeensis str. Arkansas. ELISA and immunofluorescence assays (IFAs) were also performed. Serum antibodies were detected by ELISA (anti–tandem repeat proteins 120 and 32 of E. chaffeensis; titer 1:100) and by IFA (IgG; 1:512 titer) (Figure 2).

Góngora-Biachi et al. previously reported a probable case of HME in Mexico, diagnosed by IFA only (7). More recently, E. chaffeensis was detected in 5.5% of Peromyscus spp. rodents collected from 31 sites in Mexico (8). The presence of this pathogen in a wild host is evidence of a tick–vertebrate cycle and represents a potential risk for humans exposed to these tickborne rickettsiae.

The patient we report was hospitalized within 32 days of nonspecific clinical manifestations (leukopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, increased serum transaminase concentrations, and hepatosplenomegaly), which have been reported for persistent infection (10). Some authors have suggested that the clinical triad of leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated serum transaminase levels in a febrile patient without a rash is common for patients with HME (11). For this patient, multiorgan dysfunction and hematologic abnormalities persisted despite treatment with doxycycline. Death generally results from complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome or sepsis with multiorgan failure (12).

Multiple neurologic manifestations have been reported for patients with ehrlichiosis, including severe headache, confusion, lethargy, hyperreflexia, clonus, photophobia, cranial nerve palsy, seizures, blurred vision, nuchal rigidity, and ataxia (13). The patient we report experienced changes in mental status, confusion, and a psychotic episode that was not improved by antimicrobial drug therapy.

To our knowledge, fatal cases of HME have not been reported in Mexico; they may have been ignored by clinicians or they may represent true emergence of the disease in Mexico. In a mouse model, a fatal course of infection has been associated with an Ehrlichia strain that induces a toxic shock–like syndrome with high serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α (14). Fatal infection is often confounded because the signs and symptoms can mimic findings commonly associated with other infections, such as dengue fever, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, murine typhus, or other misdiagnosed febrile diseases (15) that are common in Mexico.

Illness caused by Ehrlichia spp. results in nonspecific signs and symptoms, and diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion (8). Seasonality should be taken into account; most new cases in humans occur during the summer, when tick activity is highest. Serologic evidence of infection may be absent during the early acute phase of illness (15), but use of PCR may help confirm suspected diagnoses. In Mexico, the possibility of E. chaffeensis infection should be investigated for patients with febrile illness, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver enzymes; early diagnosis and timely treatment may prevent death.

Ms. Sosa-Gutierrez is a PhD candidate from Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Her research focuses on eco-epidemiology of tickborne rickettsial pathogens as well as vector–pathogen–host interactions, distribution, and risk factors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Donald Bouyer, Nicole Mendell, Tais B. Saito, Patricia Valdes, and Almudena Cervantes for their valuable support during diagnostic evaluations. We also thank Jere McBride for kindly providing positive control samples for ELISA and IFAs.

This project was supported by Portal del Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia (grant 2008-1 87868) and by Fondo de Investigacion en Salud, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (G13-1192). C.G.S.-G. received a scholarship for doctoral studies from the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia, Mexico. J.T. received an exclusivity scholarship from Fundacion IMSS, Mexico.

References

- Anderson BE, Dawson JE, Jones DC, Wilson KH. Ehrlichia chaffeensis, a new species associated with human ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2838–42 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Davidson WR, Lockhart JM, Stallknecht DE, Howerth EW, Dawson JE, Rechav Y. Persistent Ehrlichia chaffeensis infection in white-tailed deer. J Wildl Dis. 2001;37:538–46. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ewing SA, Dawson JE, Kokan AA, Barker RW, Warner CK, Panciera RJ, Experimental transmission of Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Rickettsiales: Ehrlichieae) among white-tailed deer by Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 1995.32:368–74.

- Sehdev AE, Dumler JS. Hepatic pathology in human monocytic ehrlichiosis. Ehrlichia chaffeensis infection. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;119:859–65 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stone JH, Dierberg K, Aram G, Dumler JS. Human monocytic ehrlichiosis. JAMA. 2004;292:2263–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dumler JS, Walker DH. Tick-borne ehrlichiosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:21–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gongóra-Biachi RA, Zavala-Velázquez J, Castro-Sansores CJ, González-Martínez P. First case of human ehrlichiosis in Mexico. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:481. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sosa-Gutiérrez CG, Vargas SM, Torres J, Gordillo-Perez MG. Tick-borne rickettsial pathogens in rodents from Mexico. J Biomed Sci Eng. 2014;7:884–9. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Dunphy PS, Luo T, McBride JW. Ehrlichia chaffeensis exploits host SUMOylation pathways to mediate effector-host interactions and promote intracellular survival. Infect Immun. 2014;82:4154–68. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dumler JS, Sutker WL, Walker DH. Persistent infection with Ehrlichia chaffeensis. J Clin Infect. 1993;17:903–5.

- Cunha BA, Chandrankunnel JG, Hage JE. Ehrlichia chaffeensis human monocytic ehrlichiosis with pancytopenia. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44:473–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yachoui R. Multiorgan failure related to human monocytic ehrlichiosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013: pii:bcr2013008716. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ratnasamy N, Everett ED, Roland WE, McDonald G, Caldwell CW. Central nervous system manifestations of human ehrlichiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:314–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ismail N, Stevenson HL, Walker DH. Role of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-10 in the pathogenesis of severe murine monocytotropic ehrlichiosis: increased resistance of TNF receptor p55- and p75-deficient mice to fatal ehrlichial infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:1846–56 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Paddock CD, Suchard DP, Grumbach KL, Hadley WK, Kerschmann RK, Abbey NW, . Brief report: fatal seronegative ehrlichiosis in a patient with HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1164–7DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 22, Number 5—May 2016

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Guadalupe Gordillo-Perez, Unidad de Investigacion Medica de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Parasitarias, 330 Cuauhtémoc Str., ZP. 06720, Mexico City, Mexico

Top