Volume 13, Number 7—July 2007

Dispatch

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Colombia

Abstract

We investigated 2 fatal cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever that occurred in 2003 and 2004 near the same locality in Colombia where the disease was first reported in the 1930s. A retrospective serosurvey of febrile patients showed that >21% of the serum samples had antibodies against spotted fever group rickettsiae.

Between July 1934 and August 1936, sixty-five cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), 62 of them fatal, were reported from Tobia, Colombia (1). No reports of this disease (known locally as Fiebre de Tobia) have been produced from Colombia since, and currently RMSF is generally not included in the differential diagnoses of febrile syndromes.

We recently confirmed RMSF as the cause of death for 2 patients by PCR (2,3), sequencing, immunohistochemical tests (4), and culture (5) (Table 1). The first patient was a 32-year-old pregnant woman (26 weeks), who had abdominal pain, headache, and fever in December 2003; pharyngitis was diagnosed, and she received amoxicillin with no improvement. A cutaneous macular rash, hepatomegaly, hyperbilirubinemia, leukocytosis, and thrombocytopenia (50,000/μL) subsequently developed. She then experienced respiratory failure and died. One of her relatives, as well as 2 dogs, had died a few days earlier with similar symptoms. Another sick dog rapidly recovered after receiving doxycycline.

The second patient was a 31-year-old previously healthy man who went to the local hospital in May 2004 with fever and severe headache; dengue was diagnosed clinically. Three days later, he became stuporous and was admitted to the hospital. Within a short period, seizures developed and he became comatose. He died a few hours later.

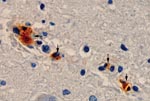

The 2 patients lived near the towns of Villeta and Tobia, Cundinamarca, Colombia. The histopathologic findings of both patients were similar and consisted of vascular congestion; interstitial edema; frequent nonoccluding thrombi (mainly in the lungs); and multiple foci of perivascular lymphocytic and monocytic infiltration in all viscera, including the brain. The lungs showed marked interstitial inflammatory infiltrates. Immunohistochemical analysis showed rickettsiae in the microvascular endothelium of all studied organs, including brain, liver, spleen, and lungs of both patients (Figure).

Several weeks after these events, we collected and identified adult male and female ticks from the farms and surroundings where the patients had lived (Table 1). We found ticks of the species Amblyomma cajennense, a known vector of spotted fever group rickettsioses in Latin America (6–9), and Rhipicephalus sanguineus, recently documented as a vector for Rickettsia rickettsii (10).

To begin to clarify the magnitude of spotted fever group rickettsioses as a public health problem in Colombia, we tested the following samples for spotted fever group rickettsiae by immunofluorescence assay (IFA) (11): 1) 64 serum samples from a national Colombian surveillance system (2001–2004) that studies malaria, dengue, and yellow fever (Instituto Nacional de Salud, Colombia); and 2) 96 serum samples from a regional (the state where the reported patients lived) surveillance system (2000–2001) for dengue (Secretaria de Salud de Cundinamarca, Colombia). Serum samples showing distinctly fluorescent rickettsiae at a >1:64 dilution were considered positive. We found immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM antibodies against spotted fever group rickettsiae (R. rickettsii was used as antigen) but not against typhus group rickettsiae (R. typhi was used as antigen) (Table 2). These data suggest that spotted fever group rickettsioses may be a frequent cause of febrile illnesses, not only in the state where the reported patients lived but also in various other regions of Colombia. Since there is strong cross-reactivity among rickettsial species when IFA is used as an antibody-detection technique, other spotted fever group rickettsiae, including those recently described in Latin America (R. parkeri and R. felis) could explain the assay results (12,13). Furthermore, most of these patients received a clinical diagnosis of dengue, an endemic disease in Colombia that appears to have become an umbrella diagnosis under which other diseases are assigned. A similar situation was recently described in Mexico (14).

RMSF in Colombia is seldom considered in the differential diagnosis for febrile disease; possible causes include the lack of an adequate diagnostic infrastructure and the invisibility of tick- and fleaborne infectious diseases in most medical curricula. The problem is further compounded by the presence of numerous agents (many transmitted by arthropod vectors) that produce nonspecific febrile syndromes during the early stages of the disease. Most of those agents are viruses that, unlike rickettsiae, have no specific treatment; thus, physicians might not feel compelled to use antimicrobial agents. Given the lack of appropriate and inexpensive diagnostic tests that are useful in the acute stage and that can be implemented in small rural hospitals, the best diagnostic tool available to healthcare personnel is clinical suspicion based on knowledge of the clinical manifestations (15), ecology, and epidemiology of rickettsioses. Physicians in areas where RMSF is endemic should consider prescribing a course of empirical treatment with doxycycline in patients who have high fever, severe headache, and myalgia, even in the absence of rash or history of tick bite, as both are frequently absent in RMSF. Such a treatment will not harm a patient with dengue or other viral infections and is likely to save the life of a patient infected with R. rickettsii.

Ms Hidalgo is a research scientist at Instituto Nacional de Salud, Bogota, Colombia. She is investigating the epidemiology of rickettsial diseases in Colombia as part of her graduate training for the PhD degree.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dario Cadena and Pablo Ocejo for allowing us to study autopsy material that they collected, and Gustavo Lopez, Efrain Benavidez, and Marcelo Labruna for teaching us the taxonomy of ticks.

This research was supported by grant 1204-04-16332 from Instituto Colombiano para el Desarrollo de la Ciencia y la Tecnología Francisco José de Caldas, Colciencias to G.V.

References

- Patino L, Afanador A, Paul JH. A spotted fever in Tobia, Colombia.Am J Trop Med.1937;17:639–53.

- Labruna MB, Whitworth T, Horta MC, Bouyer DH, McBride JW, Pinter A, Rickettsia species infecting Amblyomma cooperi ticks from an area in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, where Brazilian spotted fever is endemic.J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:90–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Eremeeva ME, Dasch GA, Silverman DJ. Evaluation of a PCR assay for quantitation of Rickettsia rickettsii and closely related spotted fever group rickettsiae.J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5466–72. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Valbuena G, Bradford W, Walker DH. Expression analysis of the T-cell–targeting chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10 in mice and humans with endothelial infections caused by rickettsiae of the spotted fever group.Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1357–69.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- La Scola B, Raoult D. Diagnosis of Mediterranean spotted fever by cultivation of Rickettsia conorii from blood and skin samples using the centrifugation-shell vial technique and by detection of R. conorii in circulating endothelial cells: a 6-year follow-up.J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2722–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ripoll CM, Remondegui CE, Ordonez G, Arazamendi R, Fusaro H, Hyman MJ, Evidence of rickettsial spotted fever and ehrlichial infections in a subtropical territory of Jujuy, Argentina.Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:350–4.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Estrada-Peña A, Guglielmone AA, Mangold AJ. The distribution and ecological ‘preferences’ of the tick Amblyomma cajennense (Acari: Ixodidae), an ectoparasite of humans and other mammals in the Americas.Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2004;98:283–92. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Childs JE, Paddock CD. The ascendancy of Amblyomma americanum as a vector of pathogens affecting humans in the United States.Annu Rev Entomol. 2003;48:307–37. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guedes E, Leite RC, Prata MC, Pacheco RC, Walker DH, Labruna MB. Detection of Rickettsia rickettsii in the tick Amblyomma cajennense in a new Brazilian spotted fever–endemic area in the state of Minas Gerais.Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100:841–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Demma LJ, Traeger MS, Nicholson WL, Paddock CD, Blau DM, Eremeeva ME, Rocky Mountain spotted fever from an unexpected tick vector in Arizona.N Engl J Med. 2005;353:587–94. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ndip LM, Fokam EB, Bouyer DH, Ndip RN, Titanji VP, Walker DH, Detection of Rickettsia africae in patients and ticks along the coastal region of Cameroon.Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:363–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Venzal JM, Portillo A, Estrada-Pena A, Castro O, Cabrewra PA, Oteo JA. Rickettsia parkeri in Amblyomma triste from Uruquay.Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1493–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zavala-Velazquez JE, Ruiz-Sosa JA, Sanchez-Elias RA, Becerra-Carmona G, Walker DR. Rickettsia felis richettsiosis in Yucatan.Lancet. 2000;356:1079–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zavala-Velazquez JE, Yu XJ, Walker DH. Unrecognized spotted fever group rickettsiosis masquerading as dengue fever in Mexico.Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:157–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chapman AS, Bakken JS, Folk SM, Paddock CD, Bloch KC, Krusell A, Diagnosis and management of tickborne rickettsial diseases: Rocky Mountain spotted fever, ehrliochioses, and anaplasmosis—United States: a practical guide for physicians and other health-care and public health professionals.MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–27.PubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Table

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 13, Number 7—July 2007

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Gustavo Valbuena, Department of Pathology, The University of Texas Medical Branch, 301 University Blvd, Galveston, TX 77555-0609, USA;

Top