Volume 17, Number 12—December 2011

Letter

Chrysosporium sp. Infection in Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnakes

To the Editor: During 2008, the ninth year of a long-term biologic monitoring program, 3 eastern massasauga rattlesnakes (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) with severe facial swelling and disfiguration died within 3 weeks after discovery near Carlyle, Illinois, USA. In spring 2010, a similar syndrome was diagnosed in a fourth massasauga; this snake continues to be treated with thermal and nutritional support and antifungal therapy. A keratinophilic fungal infection caused by Chrysosporium sp. was diagnosed after physical examination, histopathologic analysis, and PCR in all 4 snakes. The prevalence of clinical signs consistent with Chrysosporium sp. infection during 2000–2007 was 0.0%, and prevalence of Chrysosporium sp.–associated disease was 4.4% (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1%–13.2%) for 2008 and 1.8% (95% CI 0.0%–11.1%) for 2010.

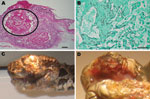

Clinical and gross necropsy abnormalities were limited to the heads of affected animals. In each case, a unilateral subcutaneous swelling completely obstructed the nasolabial pits (Figure, panel A). In the most severely affected snake, swelling extended to the cranial aspect of the orbit and maxillary fang (Figure, panel B). Notable histologic lesions were restricted to skin, gingiva, and deeper tissues of the head and cervical region and consisted of cutaneous ulcers with granulomas in deeper tissues (Figure, panel C). Ulcers had thick adherent serocellular crusts and were delineated by small dermal accumulations of heterophils and fewer macrophages. Crusts contained numerous 4–6-µm diameter right-angle branching fungal hyphae with terminal structures consistent with spores. In 1 snake, infection was associated with retained devitalized layers of epidermis consistent with dysecdysis. In the same snake, the eye and ventral periocular tissues were effaced by inflammation, but the spectacle and a small fragment of cornea remained; the corneal remnant contained few fungal hyphae.

In all snakes, in addition to deep cutaneous ulceration, the dermis, hypodermis and skeletal muscle of the maxillary and or mandibular region contained multiple granulomas, centered on variable numbers of fungal hyphae (Figure, panel D). In 1 snake, similar granulomas were also observed in maxillary gingival submucosa and subjacent maxillary bone.

Five frozen skin biopsy samples from 4 snakes were thawed and plated on Sabaroud agar; however, no fungal growth was recovered. Genomic DNA was extracted from tissue, and PCR was performed by using 2 sets of fungus-directed rRNA gene primers. The DNA was sequenced, and the 4 amplicons showed >99% homology with C. ophiodiicola (GenBank accession no. EU715819.1).

Fungal pathogens have been increasingly associated with free-ranging epidemics in wildlife, including the well-known effects of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis on frog populations globally (1) and white-nose syndrome in bats (2). Both of these diseases cause widespread and ongoing deaths in these populations that seriously threaten biodiversity across the United States (1,2). Furthermore, the emergence of keratinophilic fungi, Chrysosporium anamorph Nannizziopsis vriesii, caused fatal disease in captive bearded dragons within the past decade (3,4). Keratinophilic fungi have received considerable interest recently because of pulmonary or dermatologic disease caused in immunocompromised humans and prevalence in hospitals (5,6).

The Chrysosporium sp. fungi recently identified in the snakes from the Carlyle Lake area is molecularly related to a Chrysosporium sp. from diseased skin in a captive snake (7). Fungal diseases in reptiles are commonly secondary or opportunistic pathogens. However, Chrysosporium anamorph Nannizziopsis vriesii (3,4,8) and the Chrysosporium sp. reported here in massasaugas are occurring in animals as primary pathogens.

We describe evidence of Chrysosporium sp. causing death in free-ranging snakes. To our knowledge, this is the first reported occurrence of any similar disease syndrome in this population. Before 2008, these clinical signs had not been witnessed during radiotelemetry and mark-recapture studies or in health monitoring studies (9,10). More intensive health monitoring programs are warranted at this site, as well across this species’ range. Whether this disease represents isolated emerging incidents in Illinois or indicates more widespread concern for this species, as has been documented in bats with white-nose syndrome (2), is unclear.

Origin, transmission, and treatment of Chrysosporium sp. are unknown. The eastern massasaugas in this investigation carrying the fungal infection were from 2 discontiguous sites; therefore, direct transmission is not necessary. The occurrence across different locations and in different years suggests the organism is present in the environment, and histopathologic results indicative of primary skin involvement were consistent with environmental acquisition of infection. Potential causes for the development of lesions specifically to the head include primary trauma, high local environmental load, or disruption of the normal skin defense mechanisms.

This fungal pathogen has serious long-term implications for this population of endangered snakes. There is no indication that hikers in this environment are at risk, but continued monitoring of human and wildlife health is essential to assess environmental and zoonotic disease risks. Furthermore, if human behavior can alter disease transmission (e.g., through hiking behaviors), disease prevention at Carlyle Lake, which hosts >1 million visitors annually, will likely be unsuccessful.

References

- Skerratt LF, Berger L, Speare R, Cashins S, McDonald KR, Phillott AD, Spread of chytridiomycosis has caused the rapid global decline and extinction of frogs. EcoHealth. 2007;4:125–34. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Blehert DS, Hicks AC, Behr M, Meteyer CU, Berlowski-Zier BM, Buckles EL, Bat white-nose syndrome: an emerging fungal pathogen? Science. 2009;323:227. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pare JA, Jacobson ER. Mycotic diseases of reptiles. In Jacobson E, editor. Infectious diseases and pathology of reptiles. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2007. p. 527–71.

- Hedley J, Eatwell K, Hume L. Necotising fungal dermatitis in a group of bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps). Vet Rec. 2010;166:464–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stebbins WG, Krishtul A, Bottone EJ, Phelps R, Cohen S. Cutaneous adiaspiromycosis: a distinct dermatologic entity associated with Chrysosporium species. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:S185–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Singh I, Mishra A, Kushwaha RKS. Dermatophytes, related keratinophilic and opportunistic fungi in indoor dust of houses and hospitals. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:242–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rajeev S, Sutton DA, Wickes BL, Miller DL, Giri D, Van Meter M, Isolation and characterization of a new fungal species, Chrysosporium ophiodiicola, from a mycotic granuloma of a black rat snake (Elaphe obsolete obsolete). J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1264–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pare JA, Sigler L, Rypien KL, Gibas C-F. Cutaneous mycobiota of captive squamate reptiles with notes on the scarcity of Chrysosporium anamorph Nannizziopsis vriesii. J Herpetological Med Surg. 2003;13:10–5.

- Allender MC, Mitchell M, Phillips CA, Beasley VR. Hematology, plasma biochemistry, and serology of selected viral diseases in wild-caught eastern massasauga rattlesnakes (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) from Illinois. J Wildl Dis. 2006;42:107–14.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Allender MC, Mitchell MA, Dreslik MJ, Phillips CA, Beasley VR. Characterizing the agreement among four ophidian paramyxovirus isolates performed with three hemagglutination inhibition assay systems using eastern massasauga rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) plasma. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2008;39:358–61. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Cite This ArticleRelated Links

Table of Contents – Volume 17, Number 12—December 2011

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Matthew C. Allender, Department of Comparative Biosciences, 2001 S. Lincoln Ave, 3603 VMBSB, Urbana, IL 61802, USA

Top