Volume 18, Number 3—March 2012

Research

Lineage-specific Virulence Determinants of Haemophilus influenzae Biogroup aegyptius

Abstract

An emergent clone of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius (Hae) is responsible for outbreaks of Brazilian purpuric fever (BPF). First recorded in Brazil in 1984, the so-called BPF clone of Hae caused a fulminant disease that started with conjunctivitis but developed into septicemic shock; mortality rates were as high as 70%. To identify virulence determinants, we conducted a pan-genomic analysis. Sequencing of the genomes of the BPF clone strain F3031 and a noninvasive conjunctivitis strain, F3047, and comparison of these sequences with 5 other complete H. influenzae genomes showed that >77% of the F3031 genome is shared among all H. influenzae strains. Delineation of the Hae accessory genome enabled characterization of 163 predicted protein-coding genes; identified differences in established autotransporter adhesins; and revealed a suite of novel adhesins unique to Hae, including novel trimeric autotransporter adhesins and 4 new fimbrial operons. These novel adhesins might play a critical role in host–pathogen interactions.

For more than a century, Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius (Hae) has caused worldwide seasonal epidemics of acute, purulent conjunctivitis (1,2). In 1984, an entirely new syndrome, Brazilian purpuric fever (BPF), emerged in the town of Promissão, São Paulo State, Brazil. Caused by an emergent clone of Hae, the virulence of BPF in children was unprecedented and fatal. Invasive infection was preceded by purulent conjunctivitis that resolved before the onset of an acute bacteremic illness, which rapidly evolved into septic shock complicated by purpura fulminans (3). In the 11 years to 1995, several hundred cases of BPF were reported, of which all but 3 were in Brazil (4,5); overall mortality rate was 40%. Cases occurred sporadically and in outbreaks, mainly in small towns, although some were in the state capital, where an epidemic was feared because of crowding and deprivation. A collaborative task force by the Brazilian Health Authorities and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was created to investigate this emergent infection and identified the cause as the BPF clone of Hae (HaeBPF) (6).

After 1995, no more cases were reported for more than a decade, although cases may have been missed, submerged in periodic surges of clinically indistinguishable hyperendemic or epidemic meningococcal disease. The potential of the disease to reappear with devastating effect is, however, underscored by the recent report of a suspected outbreak (7 cases, 5 fatal within 24 hours) in 2007 in the town of Anajás in the previously unaffected Brazilian Amazon region (7); thus, it cannot be assumed that this emergent infection has gone away.

The emergence of new pathogens causing human and animal diseases represents a constant threat. Distinguishing invasive strains from their noninvasive relatives is relevant for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of the spread of emerging infectious diseases. HaeBPF constitutes a unique H. influenzae clade separate from the usual conjunctivitis-causing Hae strains (8); in experimental infections, it has caused sustained septicemia (9) and endothelial cytotoxicity (10).

However, despite intensive research spanning 2 decades, these phenotypes remain unexplained. HaeBPF, a strain of nontypeable H. influenzae (NTHI), lacks genes encoding the polysaccharide capsule, a major virulence determinant of invasive H. influenzae. Although 1 animal study has indicated that a phase-variable lipopolysaccharide structure might play a part in the serum resistance of HaeBPF (11), in other respects, a novel lipopolysaccharide has not convincingly explained its virulence (12). With regard to adhesins, Farley et al. (13) identified duplication of fimbrial (haf) genes, with sequences differing from H. influenzae type b pilin (hif), but could find no systematic difference in binding of HaeBPF and conventional Hae strains to human epithelial cells and could not conclusively implicate this locus in virulence. Various other BPF-specific outer membrane proteins potentially involved in host–pathogen interactions have been identified, including a partially characterized hemagglutinin (14) and an ≈145-kDa phase-variable protein eliciting protective immunity (15), but none have been fully characterized, and their role in disease has not been established. HaeBPF (but not other Hae strains) has a copy of the Haemophilus insertion element IS1016 (16), which has been implicated in acquisition of capsulation genes and other unspecified virulence factors in other H. influenzae strains (17,18), but its role has not been defined.

To better define the role of HaeBPF, we conducted a pan-genomic analysis. This comparison with 5 other complete H. influenzae genomes available in public databases has enabled delineation of the accessory genome for Hae and HaeBPF, characterizing all Hae-specific features that might contribute to the differences in the biology of this lineage of H. influenzae. This study goes beyond other H. influenzae pan-genome studies (19) by comparing only complete genomes and provides an absolute genomic comparison among the strains. Analysis of differences in genome content between the Hae strains and other H. influenzae revealed a plethora of novel adhesins that might play a critical role in host–pathogen interactions.

We first sequenced and annotated the genomes of the HaeBPF strain F3031 and a contemporaneous, non–BPF-associated conjunctivitis strain from Brazil, F3047. We compared strains F3031 and F3047 with H. influenzae strain Rd KW20, the type d capsule-deficient laboratory strain that was the first free-living organism to have its genome sequence determined; with H. influenzae strain 10810, a serotype b meningitis strain; with NTHI strains 86–028NP and R2846 (strain 12) (20), isolated from middle ear secretions from patients with otitis media; and with NTHI strain R2866, an unusually virulent NTHI strain isolated from a child with meningitis.

Bacterial Strains Sequenced

F3031 (GenBank accession no. FQ670178) is a BPF clone strain that is indistinguishable from other isolates by various typing systems, including multilocus sequence typing. F3047 (GenBank accession no. FQ670204) is a conjunctivitis isolate from Brazil that was established by typing to be unrelated to the BPF clone. F3031 and F3047 are described in more detail elsewhere (21).

Sequencing and Assembly

Bacterial genomes were sequenced at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Cambridge, UK. The first drafts of the F3031 and F3047 genomes were assembled from sequence to ≈7-fold coverage, from pOTWI2 and pMAQ1Sac_BstXI genomic shotgun libraries, by using BigDye Terminator chemistry on an Applied Biosystems 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). End sequences from large insert fosmid libraries in pCC1FOS (insert size 38–42 kb) were used as a scaffold for each strain. Further sequencing was performed on the Illumina Genome Analyzer (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Assemblies were created and gaps and repeat regions were bridged by read pairs and end-sequenced PCR products.

Annotation and Analysis

Coding sequences were predicted by using Glimmer 3 (www.cbcb.umd.edu/software/glimmer). Automated annotation by similarity was done by searching the Glimmer 3 coding sequence set against the National Center for Biotechnology Information Clusters of Orthologous Groups database and the SwissProt dataset (www.uniprot.org). Annotation by similarity was done by importing the NTHI strain 86–028NP annotation and comparing it with the F3031 coding sequence set by using reciprocal FASTA (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/sss/fasta). Automated annotation was confirmed by manual curation with the Artemis genome visualization tool (22). Gene definitions and functional classes were added manually by using FASTA analyses of the primary automated comparisons. tRNA genes were predicted by using tRNAScan-SE version 1.2 (23). Identification of the rRNA operons was based on similarity to homologs in the NTHI strain 86–028NP genome.

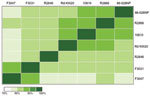

Pan-Genome Comparison

Generation of pairwise comparisons of complete genome sequences was based on alignment of basepairs in MAUVE (24), which enabled alignment of whole genome sequences despite rearrangements. For each pairwise comparison of whole-genome sequences, the length of the alignment between the 2 strains was calculated and a distance matrix was created. The distance matrix, based on the lengths of the sequence alignments, was used to create a heat map showing the clustering of strains.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Evolutionary relationships between protein-coding sequences from different strains were inferred by using MEGA version 5.02 (25). Phylogenetic trees were constructed by using sequence alignments, and a neighbor-joining tree was built under a Poisson correction substitution model assuming uniform rates of substitutions among sites.

The 7 Complete H. influenzae Genomes

Genome sizes ranged from 1.83 to 2.0 Mb (Table 1). The F3031 genome comprises 1,985,832 bp, is 8% larger than Rd KW20, and encodes 1,892 genes. The F3047 genome is larger (2,007,018 bp) and encodes 1,896 genes. All strains have a genome G+C content of 38%, typical of H. influenzae. HaeBPF strain F3031 contains an ≈24-MDa plasmid, previously sequenced and annotated (26), with average G+C content of 36.7%. This plasmid has been excluded from analysis.

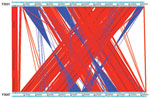

Whole-genome alignment of Hae strains F3031 and F3047 revealed substantial colinearity with 1 major rearrangement and 3 small inversions (Figure 1). Pairwise nucleotide alignments of the 7 sequences indicated a closer relatedness of the 2 Hae strains to each other than to the 5 other H. influenzae genomes (Figure 2). A core genome of 77% was shared across all 7 strains.

The Hae Accessory Genome

F3031 shares 10.6% of its genomic sequence with 1 other strain and 88% of this shared sequence (9.3% of total) with F3047, emphasizing the closer relatedness of these 2 strains to each other than to the other H. influenzae strains. A total of 163 predicted coding sequences lie within this Hae-specific DNA. A total of 99 (61%) coding sequences lie within regions of previously characterized Haemophilus bacteriophages, encoding proteins inferred by the similarity of their deduced sequences to be phage components associated with coexpressed genes transported by the phage (phage cargo). These proteins are are either homologs of conserved hypothetical proteins in other organisms or previously unidentified proteins of unknown function. Of all Hae-specific genes, >22% encoded homologs of products identified elsewhere as being involved in host–pathogen interactions; prominent members were putative adhesins and invasins not previously found in strains of H. influenzae (Figure 3). Description of the Hae accessory genome will focus on these putative adhesins.

These new Hae-specific adhesins include 4 novel fimbrial operons, unique high-molecular-weight (HMW) proteins, and a 10-member family of trimeric autotransporter adhesins (TAAs). Many of these coding sequences are associated with simple sequence repeats (SSRs), indicating that phase variation may confer the potential for antigenic variation and immune response evasion during infection.

The presence of duplicated hafABCDE operons (27) was confirmed in the F3031 and F3047 genomes. We also identified 4 more Hae-specific fimbrial gene clusters, aef1–aef4 (Figure 4). Clusters aef1–aef3 were present in both strains, although not identical (55%–100% similarity on gene-by-gene comparison), but aef4 was not present in HaeBPF F3031. Each aef operon encodes 4–6 proteins and has modest sequence identity to products of corresponding haf genes (38%–57%) and to F17 fimbrial adhesins (25%–64%) produced by pathogenic Escherichia coli associated with septicemic diarrheal diseases. Three clusters (aef1, aef3, aef4) are associated with mononucleotide SSRs of 10–17 nt located in the putative promoter region upstream of the aefA gene (Figure 4), conferring capacity for phase-variable expression through expansion and contraction of the SSR, altering efficiency of promoter binding.

The Hae genomes each encode a much richer repertoire of autotransporter adhesins than is found in other sequenced Haemophilus spp. Monomeric (classical) and novel trimeric autotransporter adhesins are present (MAA and TAA, respectively). Of the established Haemophilus autotransporter adhesins, the MAA Hap (Haemophilus adhesion and penetration protein), widely distributed in H. influenzae and proposed as a candidate NTHI vaccine antigen, is present as a pseudogene in F3031 and F3047, as previously reported by Kilian et al. (28). IgA1 protease, previously identified in the BPF clone, is also present in conjunctivitis strain F3047. Sequence alignment to other H. influenzae demonstrated that IgA1 from F3047 is more closely related to IgA1 from Rd KW20 (88% aa identity) than from F3031 (65% aa identity). Homologs of the HMW adhesins HMW1 and HMW2 (MAAs) and of the TAA H. influenzae adhesin Hia are present in F3031 and F3047. In contrast to the many NTHI strains for which substantial sequence information is available, where HMW1/HMW2 or Hia have almost always been alternatives, both are found in these Hae strains. HMW1 and HMW2, encoded at loci each consisting of 3 genes (hmwABC), were first identified in NTHI strain R2846 as HMW surface-exposed proteins, mediating attachment to human epithelial cells (29). More than 75% of NTHI encode HMW1 and HMW2, present at the same chromosomal locations in almost all HMW-containing NTHI isolates examined. hmw1A and hmw2A encode adhesins with different receptor binding specificities resulting from domains in variable regions comprising amino acid residues 114–237 of mature Hmw1A and 112–236 of mature Hmw2A (30). Despite conservation in binding specificity, hmw1A or hmw2A alleles from different isolates are highly polymorphic in the receptor binding domains (30). Hae Hmw1A– and Hmw2A–binding domain sequences (deduced from comparison with R2846 sequence) were aligned by using ClustalW (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2) with those from homologs in other NTHIs, regardless whether they were Hmw1A or Hmw2A, and the alignment was used to construct a phylogenetic tree (Figure 5). The Hae HmwA–binding domains are distinct from those in other NTHIs, suggesting that in Hae these proteins have diverged separately from other NTHIs.

In Hae F3031 and F3047, the HMW clusters are not at the homologous NTHI chromosomal position; they are elsewhere, with a 22-kb bacteriophage insertion directly downstream of hmw2ABC. The hmwA alleles are further differentiated from those found in other NTHI strains by their associated SSRs. The putative promoter region upstream of the hmw1A and hmw2A homologs contains the octanucleotide repeat unit 5′-GCATCATC-3′; there are 14 and 15 copies, respectively, in F3031 and 13 and 12 copies, respectively, in F3047. This repeat pattern contrasts with all hmwA genes so far sequenced in different NTHI strains, in which 7 basepair SSRs of either 5′-ATCTTTC-3′ or 5′-TGAAAGA-3′ in varying copy numbers are located upstream of the genes (31,32).

The Hae accessory genome includes a 10-member gene family that encodes proteins with the sequence characteristics of TAAs (Table 2). These TAAs are distinct from the Haemophilus TAAs Hsf (33), Hia (34), or the recently described Cha (35). In strains F3031 and F3047, a total of 8 genes (1–6,8,9) are present as homologs, termed tabA (for the HaeBPF trimeric autotransporter [bpf] alleles) or tahA (for the regular hae [conjunctivitis] alleles). tahA7 has no homlog in HaeBPF. The tenth gene, tabA10, is the recently described adhesin/invasin gene hadA (36). This gene is found only in HaeBPF F3031; F3047 has no corresponding gene. Each gene appears to be locus specific, sharing the same flanking regions, but sequences differ substantially between homologs 1 and 2 in particular. tabA4/tahA4, tabA5 and tabA9/tahA9 seem to be pseudogenes, carrying frameshift mutations within the coding sequence. All TAAs except tabA8/tahA8 and tabA10 (hadA) are associated with SSRs located either within the coding sequence or upstream in the putative promoter region, indicating that expression may be modulated by phase variation.

All these TAAs share the characteristic 3-domain structure of N-terminal signal peptide and C-terminal outer membrane translocator domain, separated by an internal passenger domain. However, comparison of orthologous TAAs revealed striking differences between their passenger domains for TabA1/TahA1 and TabA2/TahA2, suggesting different functions of these proteins in the 2 strains (Figure 6). The passenger domains of these proteins vary in the number of binding domains (hemagglutinin and Hep_Hag domains) and in possession of different-sized, low-complexity spacer regions consisting of approximate heptapeptide repeats. TabA1 from F3031 contains 90 copies of tandemly duplicated AASSSAS with occasional T, N, or other substitutions in many copies; TahA1 from F3047 contains 48 copies of tandemly duplicated AETAKAG with occasional R, V, or other substitutions in many copies. In the prototypic TAA YadA, a series of 15-residue repeats appears to have such a spacer function between the protein head and its anchor in the outer membrane (37), holding any receptor-binding domains away from the bacterial cell surface.

In the context of the unusual virulence of the HaeBPF clone, the tabA1 locus is particularly intriguing. Comparison with the tahA1 locus indicates not only the substantial difference between the genes themselves, in the sequence encoding the putative stalk domain, but also (in F3031) an additional gene, HIBPF06250, encoding a conserved hypothetical protein, homologous to an uncharacterized gene product in the Haemophilus cryptic genospecies strain 1595 (35). In this strain, the gene (tandem duplicated) lies downstream of the TAA Cha. In F3031, HIBPF06250 is interposed between tabA1 and IS1016 (Figure 7), and the gene (like the insertion sequence) is absent in F3047. Association of IS1016, first described as the Haemophilus capsulation locus–associated insertion sequence, with unusual and invasive virulence of NTHI strains has been suggested elsewhere (17,18), although no specific gene association has been identified.

The HaeBPF-specific Accessory Genome

The part of the Hae accessory genome unique to HaeBPF amounted to 102,304 bases (5.2% of its genome). Ten HaeBPF-specific loci ranged in size from 370 to 20,002 bases and in G+C content from 27.9% to 44.5%. Deviation from the Haemophilus average of 38% suggests that these are more recently acquired regions. Much of this DNA is located within 5 bacteriophage domains, containing all 219 coding sequences (12 Hae specific, 11 HaeBPF specific) (Table 3) and including 1 (phage region 1) now termed HP3, similar in size and gene content to Haemophilus bacteriophage HP2, found in NTHI strains associated with unusual virulence (38). The HaeBPF-specific accessory genome comprises these and another 10 coding sequences (Table 4), which remained apparently BPF specific after BLASTP analysis of their deduced amino acid sequences against the nondegenerate public databases (October 2011), which include many more Haemophilus sequences from incomplete genome sequencing projects (19). The nearest matches to these sequences were mainly homologs in other pathogenic bacterial species that occupy the same ecologic niche. One gene (hadA at BPF-specific locus 10) has recently been characterized as encoding an epithelial adhesin/invasin plausibly contributing to HaeBPF virulence (36), but the function of the others, and any part their products may play in the serum resistance of the HaeBPF clone that endows it with pathogenic potential, remains to be established. Eleven genes appear to be phage cargo (Table 3); these are either homologs of conserved hypothetical proteins identified in other organisms or entirely unknown and might represent novel virulence factors. Four F3031-specific gene products do not have homologs in any other bacterial species and cannot be assigned a putative function. Novel genes have generally formed a much larger part of newly sequenced bacterial genomes, and identification of so few unknown genes in HaeBPF strain F3031 reflects the current availability of a large amount of Haemophilus sequence data, in particular from strains of NTHI.

Although the unique virulence of the BPF clone of Hae might result from its acquisition of few (or even just 1) novel gene(s), our analysis indicates that sequence variation and variable gene expression through phase variation plausibly play a major role. Among the 21 HaeBPF-specific genes, just 1, hadA (36), is readily identifiable as a determinant of pathogenic behavior (virulence). This, however, is but 1 member of a new family of Haemophilus TAAs, which is unique to Hae but (except for hadA) shared among conjunctivitis isolates (12 diverse strains probed, unpub. data, the authors) and among members of the BPF clonal lineage (4 examples probed, unpub. data, the authors). Striking differences in sequences within the passenger domains of homologous TAAs indicate the possibility of differences in function, perhaps loss of epithelial localization through alteration of >1 of these adhesins in the HaeBPF clone. The abundance of other genes encoding putative adhesins, which differentiates Hae from other H. influenzae, underscores the early observation (39) that pilus and nonpilus factors mediate interactions of Hae with human cells in vitro. An understanding of expression of these multiple adherence factors will probably provide insights into Hae pathogenesis.

Comparison of complete, rather than draft or partially assembled, sequences leads to hypothesis-generating insights, which enable inferences as to possible gene function and clarification of phenotypic observations made before genomic information became available. For example, the pathogen-specific ≈145-kDa phase-variable protein identified by Rubin (15) can now be identified with some confidence as the intriguing TAA TabA1 (1 of few HaeBPF proteins predicted to be of this size and phase variable as a result of the SSR in the promoter region), enabling future investigations of its role in BPF virulence. The set of iron-regulated proteins identified experimentally by Smoot et al. (40) also should be identifiable by using a bioinformatic approach, greatly facilitating future study of this phenotype.

The next challenge is to experimentally test such hypotheses. Functional studies in HaeBPF have been hampered by the difficulty of genetically manipulating these strains, a difficulty that genomics does not explain. In silico analysis demonstrated that strains of Hae appear to encode all genes and regulatory sites needed for H. influenzae competence and transformation. Although small amino acid substitutions are found in most of the proteins when compared with homologs in readily transformable Rd KW20, not enough is known about their individual functions to enable prediction as to whether particular residue changes might affect function.

Our H. influenzae pan-genomic analysis demonstrated a close relationship between the HaeBPF strain F3031 and the conjunctivitis strain F3047. This finding contrasts with the remote relationship suggested by previous phylogenetic analyses (8). Analyzing complete genomes overcomes the limited discriminatory power of typing methods like multilocus sequence typing and, in this instance, supports the proposition that Hae strains are closely related and have a gene content that partially reflects their mucosal niche specificity.

The growing number of complete bacterial genomes provides increasing potential for comprehensive pan-genomic comparisons of related strains that vary in pathogenic potential. Such comparisons might reveal strain-specific features involved in virulence, which could lead to development of genotyping methods for tracking emerging pathogens and of new vaccines. Comparison of Hae with other strains of H. influenzae has detected novel candidate virulence determinants (the families of TAAs and fimbrial adhesions) that plausibly confer selective advantages in adapting to upper respiratory tract and conjunctival mucosae. It is tempting to speculate that alteration through mutation in the specificity of adhesins such as the TAAs might, as with HaeBPF, have created a maladaptive phenotype less firmly localized to the mucosal surface and able to invade the bloodstream. To investigate the role that the novel family of TAAs might play in host–pathogen interactions, we are conducting in vitro studies of gene function.

Dr Strouts is a postdoctoral research fellow at Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, USA. She conducted this work as part of her doctoral thesis. Her research interests include host gene expression patterns in response to systemic infectious diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank the core sequencing and informatics groups at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute for sequencing the bacterial genomes, and we thank Leonard W. Mayer for providing chromosomal DNA from the CDC archive of BPF clone strains.

This study was supported by grants to J.S.K. from the Health Protection Agency, Porton Down, Salisbury, UK, The Imperial College Trust. Genome sequencing at the Pathogen Sequencing Unit, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, was supported from the core grant from the Wellcome Trust in response to a project proposal submitted by J.S.K.

References

- Koch R. Report on activities of the German Cholera Commission in Egypt and East India [in German]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1883;1548–51.

- Weeks JN. The bacillus of acute catarrhal conjunctivitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1886;15:441–51.

- Harrison LH, da Silva GA, Pittman M, Fleming DW, Vranjac A, Broome CV. Epidemiology and clinical spectrum of Brazilian purpuric fever. Brazilian Purpuric Fever Study Group. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:599–604.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- McIntyre P, Wheaton G, Erlich J, Hansman D. Brasilian purpuric fever in central Australia. Lancet. 1987;330:112. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Virata M, Rosenstein NE, Hadler JL, Barrett NL, Tondella ML, Mayer LW, Suspected Brazilian purpuric fever in a toddler with overwhelming Epstein-Barr virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:1238–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Harrison LH, Simonsen V, Waldman EA. Emergence and disappearance of a virulent clone of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius, cause of Brazilian purpuric fever. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:594–605. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Santana-Porto EA, Oliveira AA, da Costa MRM, Pinheiro AS, Oliveira C, Lopes ML, Suspected Brazilian purpuric fever, Brazilian Amazon region. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:675–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Erwin AL, Sandstedt SA, Bonthuis PJ, Geelhood JL, Nelson KL, Unrath WC, Analysis of genetic relatedness of Haemophilus influenzae isolates by multilocus sequence typing. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1473–83. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rubin LG, Gloster ES, Carlone GM. An infant rat model of bacteremia with Brazilian purpuric fever isolates of Hemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius. Brazilian Purpuric Fever Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:476–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Weyant RS, Quinn FD, Utt EA, Worley M, George VG, Candal FJ, Human microvascular endothelial cell toxicity caused by Brazilian purpuric fever–associated strains of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:430–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rubin LG, Peters VB, Ferez MC. Bactericidal activity of human sera against a Brazilian purpuric fever (BPF) strain of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius correlates with age-related occurrence of BPF. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1262–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Erwin AL, Munford RS. Comparison of lipopolysaccharides from Brazilian purpuric fever isolates and conjunctivitis isolates of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius. Brazilian Purpuric Fever Study Group. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:762–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Farley MM, Whitney AM, Spellman P, Quinn FD, Weyant RS, Mayer L, Analysis of the attachment and invasion of human epithelial cells by Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius. J Infect Dis. 1992;165(Suppl 1):S111–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Barbosa SF, Hoshino-Shimizu S, Alkmin MG, Goto H. Implications of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius hemagglutinins in the pathogenesis of Brazilian purpuric fever. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:74–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rubin LG. Role of the 145-kilodalton surface protein in virulence of the Brazilian purpuric fever clone of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius for infant rats. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3555–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dobson SR, Kroll JS, Moxon ER. Insertion sequence IS1016 and absence of Haemophilus capsulation genes in the Brazilian purpuric fever clone of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius. Infect Immun. 1992;60:618–22.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Karlsson E, Melhus A. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae strains with the capsule-associated insertion element IS1016 may mimic encapsulated strains. APMIS. 2006;114:633–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Satola SW, Napier B, Farley MM. Association of IS1016 with the hia adhesin gene and biotypes V and I in invasive nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5221–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hogg JS, Hu FZ, Janto B, Boissy R, Hayes J, Keefe R, Characterization and modeling of the Haemophilus influenzae core and supragenomes based on the complete genomic sequences of Rd and 12 clinical nontypeable strains. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R103. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Barenkamp SJ, Leininger E. Cloning, expression, and DNA sequence analysis of genes encoding nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae high-molecular-weight surface-exposed proteins related to filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1302–13.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brenner DJ, Mayer LW, Carlone GM, Harrison LH, Bibb WF, Brandileone MC, Biochemical, genetic, and epidemiologic characterization of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius (Haemophilus aegyptius) strains associated with Brazilian purpuric fever. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1524–34.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Carver T, Berriman M, Tivey A, Patel C, Böhme U, Barrell BG, Artemis and ACT: viewing, annotating and comparing sequences stored in a relational database. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2672–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–64. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. MAUVE: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–403. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kroll JS, Farrant JL, Tyler S, Coulthart MB, Langford PR. Characterisation and genetic organisation of a 24-MDa plasmid from the Brazilian purpuric fever clone of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius. Plasmid. 2002;48:38–48. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Read TD, Dowdell M, Satola SW, Farley MM. Duplication of pilus gene complexes of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6564–70.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kilian M, Poulsen K, Lomholt H. Evolution of the paralogous hap and iga genes in Haemophilus influenzae: evidence for a conserved hap pseudogene associated with microcolony formation in the recently diverged Haemophilus aegyptius and H. influenzae biogroup aegyptius. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:1367–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- St Geme JW III, Falkow S, Barenkamp SJ. High-molecular-weight proteins of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae mediate attachment to human epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2875–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Giufrè M, Muscillo M, Spigaglia P, Cardines R, Mastrantonio P, Cerquetti M. Conservation and diversity of HMW1 and HMW2 adhesin binding domains among invasive nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae isolates. Infect Immun. 2006;74:1161–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dawid S, Barenkamp SJ, St Geme JW III. Variation in expression of the Haemophilus influenzae HMW adhesins: a prokaryotic system reminiscent of eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1077–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Power PM, Sweetman WA, Gallacher NJ, Woodhall MR, Kumar GA, Moxon ER, Simple sequence repeats in Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:216–28. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- St Geme JW III, Cutter D, Barenkamp SJ. Characterization of the genetic locus encoding Haemophilus influenzae type b surface fibrils. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6281–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Barenkamp SJ, St Geme JW III. Identification of a second family of high-molecular-weight adhesion proteins expressed by non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1215–23. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sheets AJ, Grass SA, Miller SE, St Geme JW III. Identification of a novel trimeric autotransporter adhesin in the cryptic genospecies of Haemophilus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:4313–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Serruto D, Spadafina T, Scarselli M, Bambini S, Comanducci M, Höhle S, HadA is an atypical new multifunctional trimeric coiled-coil adhesin of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius, which promotes entry into host cells. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:1044–63. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mota LJ, Journet L, Sorg I, Agrain C, Cornelis GR. Bacterial injectisomes: needle length does matter. Science. 2005;307:1278. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Williams BJ, Golomb M, Phillips T, Brownlee J, Olson MV, Smith AL. Bacteriophage HP2 of Haemophilus influenzae. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6893–905. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- St Geme JW III, Gilsdorf JR, Falkow S. Surface structures and adherence properties of diverse strains of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3366–71.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Smoot LM, Bell EC, Crosa JH, Actis LA. Fur and iron transport binding proteins in the Brazilian purpuric fever clone of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:629–36. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Cite This Article1Current affiliation: Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, USA.

Table of Contents – Volume 18, Number 3—March 2012

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![Thumbnail of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius (Hae)–specific features (163 coding sequences [CDSs]) determined from the pan-genome comparison. Putative virulence factors (red) accounted for ≈22% (13 CDSs) of all features identified.](/eid/images/11-0728-F3-tn.jpg)

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

J. Simon Kroll, Imperial College London, Medicine, St Mary’s Hospital campus, Norfolk Place, London W2 1PG, UK

Top