Volume 15, Number 8—August 2009

Dispatch

Human Rabies and Rabies in Vampire and Nonvampire Bat Species, Southeastern Peru, 2007

Abstract

After a human rabies outbreak in southeastern Peru, we collected bats to estimate the prevalence of rabies in various species. Among 165 bats from 6 genera and 10 species, 10.3% were antibody positive; antibody prevalence was similar in vampire and nonvampire bats. Thus, nonvampire bats may also be a source for human rabies in Peru.

Rabies is one of the better known encephalitis viruses of the family Rhabdoviridae and genus Lyssavirus. In the sylvatic cycle, this infection is maintained as an enzootic disease in several species, such as foxes, raccoons, and bats. The hematophagous bat, Desmodus rotundus, is the main vector and reservoir for sylvatic human rabies in South America (1), in contrast with other areas in the world where dogs serve as the main source of infection for humans in the urban cycle.

During December 2006–March 2007, a total of 23 human sylvatic rabies cases occurred in Puno (n = 6) and Madre de Dios (n = 17), Peru. The affected population consisted mainly of gold miners and their families who relocate to the area during the rainy season for small-scale mining before returning to their original towns for agricultural activities during the rest of the year. A vampire bat (D. rotundus) rabies virus variant was identified from clinical samples of deceased patients (2).

After the rainy season ended, a team from the US Naval Medical Research Center Detachment, the Ministerio de Salud (Peruvian Ministry of Health), the Servicio Nacional de Sanidad Agraria (Agricultural Health Service), and the Museo de Historia Natural (Natural History Museum) from the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (San Marcos University) traveled to the area to conduct bat collections. The objective of the survey was to identify the prevalence of rabies infection among hematophagous (vampire) and nonhematophagous bats and to assess the distribution of bat genera within the outbreak area.

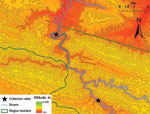

We sampled 2 study sites (A and B) for this survey. The first collection was conducted in the region of Madre de Dios (location A, 13° 7′53.53′′S, 70°24′28.27′′W) from May 2 through May 4, 2007. The second site was located in the region of Puno (location B, 13°15′29.57′′S, 70°19′39.14′′W) and sampled from May 6 through May 10, 2007 (Figure). Both trapping sites were located within 1 km of reported rabies cases in humans.

Bats were collected by using mist nets. These nets were situated along the river banks, in secondary forests, and in manioc and banana plantations. In addition to the above habitats, bats in location B were collected in cattle grazing areas and in 2 caves. Mist nets were set out every afternoon before dusk, checked every 1.5 hours, and closed at midnight, after 7 hours.

Bats were removed from mist nets by using protective leather gloves. Each animal was placed inside a canvas bag, transported to a processing location, and kept until the following morning when they were processed as previously described (3). Brain tissues and blood samples collected on necropsy were kept in a liquid nitrogen container for storage and shipping to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, GA, USA. Carcasses were tagged and stored in formalin for shipment to the Museo de Historia Natural in Lima for positive species identification.

Blood samples processed at CDC were tested for rabies virus–specific antibodies by using a rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test (RFFIT). Brain stems were tested by direct fluorescence antibody (DFA) for evidence of active disease. Antibody prevalence was calculated by using the binomial exact method; antibody prevalence rates between bat species, location, and genera were compared by using the χ2 and Fisher exact tests. All analyses were performed with Stata 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

A total of 195 bats were captured. All brain tissues were negative for rabies infection by DFA. Sufficient quantity of serum for RFFIT was available from only 165 (85%) of the sampled animals, which were included in this study. The bats that were collected represented 6 genera, including 10 species; 103 (62%) were females; 62 (38%), males; 25 (15%), juveniles; 140 (85%, adults; and 125 (76%) were Carollia spp. (Table 1). One hundred thirty-seven animals (83%) were collected from community B. All vampire bats (n = 7) were collected in this location as well as other non-Carollia insectivorous and frugivorous bats (p = 0.001).

Bats from the genus Carollia were collected more frequently from natural, non-disturbed refuges (e.g., creeks, caves), while other insectivorous, frugivorous, and vampire bats were found in more visibly disturbed or modified foraging areas (e.g., plantations, cattle farms) (p<0.001). Seventeen bats were antibody positive to rabies virus (cut-off value 0.5 IU), for an antibody prevalence of 10.3% (95% confidence interval 6.1–16.0). Antibody prevalence was similar (p = 1.000) among vampire bats (1/7, 14%), Carollia spp. (12/125, 10%), and other nonvampire bat genera (Uroderma, Sturnira, Platyrhinus, and Artibeus) (4/33, 12%) (Table 2). No statistical differences were found between antibody prevalence and sex (p = 0.111), age (p = 0.078), habitat (p = 1.000), or collection site (p = 1.000) using Fisher exact test.

In recent years, cases of rabies among humans in urban areas (transmitted by domestic animals) have declined considerably in the Americas. This is likely the result of an aggressive initiative by the member states of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) to eliminate urban rabies in the Americas (4). Consequently, rabies infections acquired by humans from wild animals, or sylvatic rabies, now represents the primary source for human infection in the region (1), with a similar trend for Peru (5).

Haematophagous bats, including D. rotundus, are usually the species associated with sylvatic bat rabies outbreaks in South America, but little is known about the role of nonhematophagous bats. An investigation in Chile found that nonvampire bats may in fact serve as adequate vectors of sylvatic rabies and even confirmed a single human infection of nonvampire-bat variant rabies linked to a nonhematophagous bat (6,7). Likewise, PAHO reported 3 cases of sylvatic rabies transmitted by nonhematophagous bats in 2004 (4). This may suggest that insectivorous and frugivorous bats have a more specific role in the transmission of rabies virus in South America.

The antibody prevalence of 10.3% found in our study is concordant with the 37% antibody rates found in nonhematophagous bats in Colima, Mexico (8) and 7.6% and 12.8% antibody prevalence among vampire and nonvampire bats in Grenada and Trinidad, respectively (9). Although the transmission of rabies virus seems to occur very early in life (10,11), our study did not demonstrate evidence of antibodies to the virus among juvenile bats. Likewise, the distribution of gender suggested higher antibody prevalence among females, although the finding was not significant, perhaps due to small sample size.

The different distribution of bat species may be related to food availability, which would explain why D. rotundus bats were found near cattle farms and the more ubiquitous distribution of Carollia perspicillata bats, which feed primarily on fruit in addition to pollen and insects. The bat species collected in our study have been previously found in areas at similar altitudes in Peru; therefore, their distribution in this area follows a regular pattern (12,13). Additionally, the lack of surveillance for bat populations in the area prevents further inference about a possible source of infection among these bat populations. Although none of the bats tested in our investigation had active rabies infections, both vampire and nonvampire bats had evidence of antibodies to rabies virus, which perhaps suggests ongoing cross-species transmission (spillover) among multiple bat species.

Peru and other South American countries should enforce the comprehensive, more aggressive preventive measures suggested at the XI Reunion de Directores de los Programas Nacionales de Control de Rabia en America Latina (Meeting of the Directors of National Rabies Control Programs in Latin America) for certain prioritized areas. These activities include preexposure prophylaxis, surveillance, closer coordination with local animal health authorities, and community education.

Ms Salmón-Mulanovich is a PhD student in the International Health Department, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Her main interests are the epidemiology of zoonotic diseases and the application of geographic information systems for public health and disease modeling.

Acknowledgments

The experiments reported herein were conducted in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and in accordance with the principles set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (14). All specimens were collected with the authorization of the Instituto Nacional de Recursos Naturales of Peru (permit no. 068-2007-INRENA-IFFS-DCB).

This work was funded by US Department of Defense Global Emerging Infections Surveillance and Response System and supported by work unit no. 847705 82000 25GB B0016.

References

- Schneider MC, Belloto A, Ade MP, Unidad de Salud Publica Veterinaria Orgainzación Panamericana de la Salud, Leanes LF, Correa E, et al. Situacion epidemiologica de la rabia humana en America Latina en el 2004. Boletin Epidemiologico. 2005;26:2–4.

- Gomez-Benavides J, Manrique C, Passara F, Huallpa C, Laguna VA, Zamalloa H, Outbreak of human rabies in Madre de Dios and Puno, Peru, due to contact with the common vampire bat, Desmodus rotundus. In: Proceedings of 56th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; 2007 Nov 4–8; Philadelphia, PA, USA. p. 150–99.

- Mills JN, Childs JE, Ksiazek TG, Peters CJ, Velleca WM. Methods for trapping and sampling small mammals for virologic testing. 1995 [cited 2007 Feb 23] Available from http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/spb/mnpages/rodentmanual.htm

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Vigilancia epidemiologica de la rabia en las Americas, 2004. [cited 2006 Oct 5]. Available from http://bvs.panaftosa.org.br/textoc/bolvera2004.pdf

- Navarro A, Bustamante NJ, Sato SA. Situaciόn actual y control de la rabia en el Peru. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública. 2007;24:46–50.

- de Mattos CA, Favi M, Yung V, Pavletic C, de Mattos CC. Bat rabies in urban centers in Chile. J Wildl Dis. 2000;36:231–40.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Favi M, de Mattos CA, Yung V, Chala E, Lopez LR, de Mattos CC. First case of human rabies in Chile caused by an insectivorous bat virus variant. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:79–81. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Salas-Rojas M, Sánchez-Hernández C Romero-Almaraz MdL, Schnell GD, Schmid RK, et al. Prevalence of rabies and LPM paramyxovirus antibody in non-hematophagous bats captured in the Central Pacific coast of Mexico. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2004;98:577–84. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Price JL, Everard CO. Rabies virus and antibody in bats in Grenada and Trinidad. J Wildl Dis. 1977;13:131–4.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Steece RS, Calisher CH. Evidence for prenatal transfer of rabies virus in the Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis Mexicana). J Wildl Dis. 1989;25:329–34.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Steece R, Altenbach JS. Prevalence of rabies specific antibodies in the Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis mexicana) at Lava Cave, New Mexico. J Wildl Dis. 1989;25:490–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Graham GL. Changes in bat species diversity along an elevational gradient up the Peruvian Andes. J Mammal. 1983;64:559–71. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Patterson BD, Stotz DF, Solari S, Fitzpatrick JW, Pacheco V. Contrasting patterns of elevational zonation for birds and mammals in the Andes of southeastern Peru. J Biogeogr. 1998;25:593–607. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Institute of Laboratory Animals Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington: National Academy Press; 1996.

Figure

Tables

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 15, Number 8—August 2009

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Joel M. Montgomery, Emerging Infections Program, US Naval Medical Research Center Detachment, 3230 Lima Pl, Washington, DC 20521-3230, USA

Top