Volume 15, Number 8—August 2009

About the Cover

For the world does not yet censure Those who tread the paths of dreams

―Ono no Komachi

“Gourd-shaped legs and wriggling worm lines” is how a Japanese critic described the style of early Torii artists of the Edo period (1615–1868). Named after the bustling city that would become present-day Tokyo, this period was marked by peace and a thriving urban culture. The most characteristic expression was ukiyo-e or the floating world, which concerned itself with the fleeting activities of everyday life. The genre produced poetry and drama but most of all, woodblock prints that inspired the global art scene of succeeding generations.

Fodder for ukiyo-e came from Edo’s entertainment districts, with their teahouses and other establishments frequented by actors, courtesans, and throngs of spectators. A major source was Kabuki, a form of classical Japanese theater that featured both heroic and ordinary figures in plays filled with spectacular costumes and scenery. Another was woodblock prints, depicting lively scenes from these plays in posters, play bills, and storybooks. These became a source of pride for printmakers, who would sign them as “An artist of Japan.” A group known as the Torii School achieved success and popularity with highly skilled designs that captured the boisterous energy of Kabuki acting and the authentic Japanese spirit that fueled the period. Kiyomasu I was member of that school and, as often the custom, adopted its name.

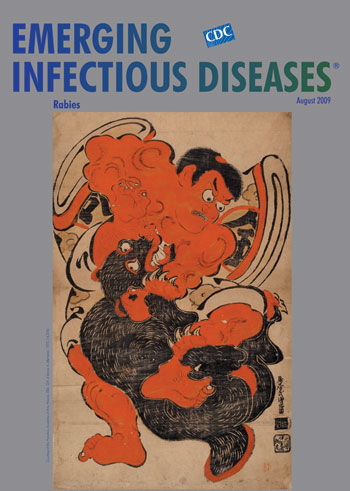

Torii Kiyomasu I was one of the earliest masters of floating-world scenes. Details of his life and work are sketchy and intertwined with those of other founders of the Torii School, but his surviving work is considered more accomplished than theirs. Unlike most designs cut in blocks of wood during this period, his were marked by fluid calligraphic lines and contained areas of orange lead pigment applied by hand with stencils. His theatrical characters burst out the edges of the paper. Caught as they were in the middle of intense activity, they exuded a thick physicality, their muscles quivering, twisted, or coiled; their gestures slicing through the air.

Kintoki Wrestling with a Black Bear, on this month’s cover, showcases Kiyomasu’s bold design and his preoccupation with movement, as well as the period’s inclination to blend art with legend, image with words, often adding contemplative verses to expand a visual theme. Kintoki was a mythical character. Known as Kintarō in his younger years, he was a child hero, a larger than life latter-day Hercules, who dazzled with his strength and ability to overcome obstacles. Kintoki dreamed big, fought monsters, spoke the language of animals, wrestled with bears, and always won.

Kintoki’s struggle with the black bear seems emblematic on several levels. Here is a Japanese artist, Kiyomasu I, in the throes of a struggle for independence and identity, breaking away from traditional ways, many of them borrowed from People’s Republic of China, and venturing into new, more authentic expression. Then there is Kintoki, the national hero, in a steamy scene towering over a wild beast, his muscles straining, eyes bulging, gourd legs curling, garments flying through the air. If he did speak the bear’s language, what was he saying through clenched teeth? On yet another level, Kiyomasu’s print is a symbol of the human struggle against the wild, against brute strength requiring heroic intervention and against infections challenging the fringes of human purview.

Many of these are infections spreading from animals to humans. Rabies is one of them, a disease known since antiquity. Homer mentioned “raging dogs” in the Iliad and wrote that Sirius, the dog star of the Orion, exerted a malignant influence on human health. In Japan, rabies existed since the 10th century and was part of life during the Edo period. Wildlife rabies was also known. George Fleming, in his book Rabies and Hydrophobia (1872), wrote of a rabid bear in the French city of Lyon causing havoc in the year 900. But for Kintoki, overcoming the bear was a matter of power and skill. The match was fair. The strongest contestant won. No virus was involved, even if rabies had not yet been eliminated in Japan, as it would be in the 1950s.

In North America, dog rabies was introduced by European settlers in the 1700s. Compulsory vaccination programs after World War II controlled the disease, and in 2007, dog rabies was declared eliminated in the United States. All the same, wildlife rabies increased. The disease source shifted from domesticated animals to mainly raccoons, skunks, foxes, and bats, and rabies reemerged as a major zoonosis.

“The only remedy is to throw the patient unexpectedly into a pond, and if he has not a knowledge of swimming to allow him to sink, in order that he may drink, and to raise and again depress him, so that though unwillingly, he may be satisfied with water; for thus at the same time both the thirst and dread of water is removed.” This remedy, described by Celsus, a physician and naturalist of antiquity, was one of many outlandish approaches against rabies. Chinese physicians offered, among other “cures,” a mixture of musk and cinnabar suspended in rice spirits. But it was vaccination programs that finally controlled the disease in many areas of the world and even eliminated it in a few.

Kintoki’s struggle with the black bear brings back the specter of lyssa. With increased disease in free-ranging animals, public health workers have to reach deeper in their bag of tricks for yet more safe and cost-effective solutions. And like the Japanese strongman, they must imagine that they can overcome all obstacles and eliminate all scourges, even rabies. Ongoing wildlife epizootics could reintroduce the disease in unvaccinated domesticated animals, perpetuating the problem for all of us. If rabies exists somewhere, it exists everywhere. For as the poet put it, “… The moon shining/over Niho Bay/is the very same/as at Suma and Akashi.”

Bibliography

- A rare exhibition of Torii masters [cited 2009 Jun 5]. Available from http://www2.hawaii.edu/~charlot/John%20WEB%20HON/HON%20Torii%20copy.pdf

- Baer GM, ed. The natural history of rabies. New York: Academic Press; 1975.

- Daring moves: Kabuki actor prints [cited 2009 Jun 4]. Available from http://www.honoluluacademy.org/cmshaa/academy/index.aspx?id=1543

- Lane R. Images of the floating world. Old Saybrook (CT): Konecky and Konecky; 1978.

- Mason P. History of Japanese art. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Pearson Prentice Hall; 2005.

- Michener JA. The floating world. New York: Random House; 1954.

- Narasaki M, ed. Hizō Ukiyo-e taikan-1, Vol 2. Tokyo: Kodansha; 1987.

- Ono no Komachi’s poetry [cited 2009 Jun 3]. Available from http://www.gotterdammerung.org/japan/literature/ono-no-komachi

- Singer I. Picture-poems, poem-pictures [cited 2009 Jun 5]. Available from http://www.hms.org.il/Museum/Templates/showpage.asp?DBID=1&LNGID=1&TMID=84&FID=1217&PID=0

- Velasco-Villa A, Reeder SA, Orciari LA, Yager PA, Franka R, Blanton JD, et al. Enzootic rabies elimination from dogs and reemergence in wild terrestrial carnivores, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1849–54. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Related Links

Table of Contents – Volume 15, Number 8—August 2009

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Polyxeni Potter, EID Journal, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Rd NE, Mailstop D61, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA

Top