Volume 17, Number 3—March 2011

About the Cover

From My Rotting Body, Flowers Shall Grow, and I Am in Them, and That Is Eternity

—Edvard Munch

“My afflictions belong to me and my art―they have become one with me. Without illness and anxiety, I would have been a rudderless ship,” wrote Edvard Munch, acknowledging that pain and suffering fueled his creativity and guided his art. In an era gripped by world wars and a deadly flu pandemic and shaken by Sigmund Freud and Charles Darwin, he sought to recreate his troubled childhood and his lifelong struggle with physical and mental illness. “My art is really a voluntary confession and an attempt to explain to myself my relationship with life―it is, therefore, actually a sort of egoism, but I am constantly hoping that through this I can help others achieve clarity.”

Childhood trauma started at age 5, when his mother died of tuberculosis, and continued at 13 with loss of his beloved sister Sophie to the same disease. The deaths unsettled this Norwegian household already compromised by poverty. The family lived in tenement housing plagued by tuberculosis and bronchitis―scourges of the working class. The father, an underpaid medical officer, was “temperamentally nervous and obsessively religious―to the point of psychoneurosis.” Another sister had to be hospitalized for mental illness. A brother died. “Often I awoke in the middle of the night, gazing around the room in wild fear―was I in hell?” Munch had childhood bouts of respiratory infections, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and rheumatic fever. “I inherited two of mankind’s most frightful enemies―consumption and insanity.”

After a stint as engineering student to appease his father, he enrolled in art school to study painting, “an unholy trade.” He fell in with a bohemian crowd, absorbing their philosophy for a lifetime; came under the influence of anarchist and nihilist Hans Jaeger, who admonished him to “write his life”; and enrolled in the Royal School of Art and Design of Christiania (now Oslo) to study under naturalist painter Christian Krohg. His early work, which experimented with various styles, was labeled “unfinished” and was viewed with universal hostility as “impressionism carried to the extreme.”

Munch did not reject any of the styles he studied at home or later in Paris, where he worked under Léon Bonnat. He used naturalism, impressionism, and linear concepts such as those in the work of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Art Nouveau practitioners. Like his friends Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg, he had a flair for drama, which he developed fully in sets with characters inside his paintings. Like the symbolists, with whom he is often identified, he used metaphorical elements to create emotional scenes and avoided perspective, chiaroscuro, and naturalistic color. Instead he used stylized or exaggerated objects, moods, and thoughts. In his mature works, canvas and painted surface became a means of expression and he the forerunner of a new modernist movement, expressionism.

Increasingly concerned with the expressive representation of emotions, he addressed the fundamental elements of human experience―birth, love, death―over and over again, exploring them throughout his life, which was filled with unsatisfactory relationships, a hostile public, continued illness, breakdowns and hospitalizations, and a bout in 1918 of the Spanish Flu. These he transformed into art filled with melancholy. He died of pneumonia at 80.

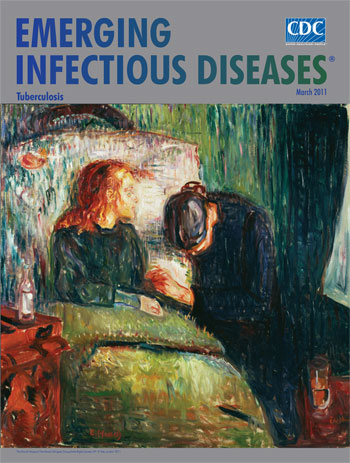

Munch considered The Sick Child, on this month’s cover, his first “soul painting,” a break from impressionism. He painted the subject six times and also explored it in lithography, drypoint, and etching. The painting was not well received because of its “roughness” and “sketchiness.” But Christian Krohg liked it: “He sees only the essential, and that, naturally, is all he paints. For this reason Munch’s pictures are as a rule ‘not complete.’”

“As for The Sick Child,” Munch wrote, “it was the period I think of as the age of the pillow.” Many artists did pictures of children on their pillows. “What I wanted to bring out―is that which cannot be measured―I wanted to bring out the tired movement in the eyelids―the lips must look as though they are whispering―she must look as though she is breathing―I want life―what is alive.” Since hailed as the first expressionist masterpiece, the painting shows his sister Sophie, on her deathbed, turned toward a dejected figure nearby. The composition is cramped and isolating, patient and mourner trapped in their predicament.

The emotional effect comes not from a naturalistic physical presentation but from somewhere within the figures. The light emanates from the pillow and from the face of the girl, which seems transparent, a fever-induced vision already in the world of spirits. The mask-like features and color patchiness, the lack of facial expression betray the nature of the child’s illness. The woman at the bedside, head bowed against the contracted chest, hands resting on the blanket, grieves inwardly. This non-violent display of emotion resonates, as if the nervous excitement not discharged in muscular action fuels associations of melancholy to arouse increased feeling. The painting is the artist’s recall of his own response to the death scene. “I do not paint what I see. I paint what I have seen.”

The paint is thinned and scored for intensity, the strong surrounding colors contrasting with the faint face of the child. Red on the furniture, the child’s hair, and repetitively in the background invokes blood, harbinger and dominant presence of tuberculosis in the scene.

The Sick Child portrays a dying adolescent, her physical and spiritual attractiveness heightened, as was believed, by her very illness. The pathos of youth caught between life and death recalls the words of John Keats (1795–1821), whose own life and immense promise were cut short by tuberculosis. The poet embraced the opposites in life: love and loss, pleasure and pain, the “inextricable contrarieties of life,” part of the human condition. Therefore, beauty, joy, and life are valuable because they are transitory and eventually become their very opposites. And so does Melancholy, “She dwells with Beauty―Beauty that must die; / And Joy, whose hand is ever at his lips / Bidding adieu; and aching Pleasure nigh, / Turning to Poison while the bee-mouth sips.”

Consumptive drama has subsided in our times, with tuberculosis viewed less as romantic tragedy or isolating contagion and more as serious but treatable disease. Sadly still a global threat, particularly among AIDS patients and the underprivileged, tuberculosis remains as debilitating and traumatizing as in Munch’s experience and art, even though the tubercle bacillus as its etiologic agent was discovered during his lifetime.

The relationship between illness and creativity, embraced as pivotal by Munch though a long-standing academic discussion, has run the gamut from prophetic to tiresome. But Keats’ notion of “inextricable contrarieties” still works. The genius of human invention exemplified by Robert Koch (1843–1910) and so many others inevitably meets its direct opposite, logistical failure or failure of will. Thus such brilliant discoveries as knowing what causes tuberculosis, how it is spread, and how to treat it have not yet eliminated this disease. “Aye, in the very temple of Delight / Veiled Melancholy has her sov’reign shrine.”

Bibliography

- Castro KG, LoBue P. Bridging implementation, knowledge, and ambition gaps to eliminate tuberculosis in the United States and globally. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:337–42.

- Cordulack SW. Edvard Munch and the physiology of symbolism. London: Associated University Presses; 2002.

- Eggum A. Edvard Munch: paintings, sketches, and studies. New York: CN Potter; 1984.

- Heller R. Munch: his life and work. London: Murray; 1984.

- Lande M. The life of Edvard Munch [cited 2011 Feb 7]. http://www.munch.museum

- Langaard JH, Revold R. Edvard Munch. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1963.

- Prideaux S. Behind the scream. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2006.

Related Links

Table of Contents – Volume 17, Number 3—March 2011

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Polyxeni Potter, EID Journal, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Rd NE, Mailstop D61, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA

Top