Volume 23, Number 7—July 2017

Research

Competence of Aedes aegypti, Ae. albopictus, and Culex quinquefasciatus Mosquitoes as Zika Virus Vectors, China

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

In China, the prevention and control of Zika virus disease has been a public health threat since the first imported case was reported in February 2016. To determine the vector competence of potential vector mosquito species, we experimentally infected Aedes aegypti, Ae. albopictus, and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes and determined infection rates, dissemination rates, and transmission rates. We found the highest vector competence for the imported Zika virus in Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, some susceptibility of Ae. albopictus mosquitoes, but no transmission ability for Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes. Considering that, in China, Ae. albopictus mosquitoes are widely distributed but Ae. aegypti mosquito distribution is limited, Ae. albopictus mosquitoes are a potential primary vector for Zika virus and should be targeted in vector control strategies.

Zika virus is a mosquitoborne flavivirus that poses a serious threat worldwide (1). Because cases of Zika virus disease in humans have been sporadic and symptoms mild, Zika virus has been neglected since its discovery in 1947 (2,3). The first major Zika virus outbreak was reported on Yap Island in Micronesia in 2007 (4). However, the Zika virus disease outbreak in French Polynesia during 2012–2014 surprised the public health communities because of the high prevalence of Guillain-Barré syndrome (5). In addition, the ongoing Zika virus epidemic in the Americas since 2015 was associated with congenital infection and an unprecedented number of infants born with microcephaly (6,7). In 2015, the Zika virus epidemic spread from Brazil to 60 other countries and territories; active local virus transmission (8) and cases of imported Zika virus disease are occurring all over the world (9,10). In view of the seriousness of the epidemic, the World Health Organization declared the clusters of microcephaly and Guillian-Barré syndrome a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (11).

Experimental studies have confirmed that Aedes mosquitoes, including Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus, Ae. vittatus, and Ae. luteocephalus, serve as vectors of Zika virus (12–15). However, vector competence (ability for infection, dissemination, and transmission of virus) differs among mosquitoes of different species and among virus strains. Ae. aegypti mosquitoes collected from Singapore are susceptible and could potentially transmit Zika virus after 5 days of infection; however, no Zika virus genome has been detected in saliva of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes in Senegal after 15 days of infection (12,14). Ae. albopictus mosquitoes are a secondary vector for Zika virus transmission (16). In Italy, the population transmission rate is lower and the extrinsic incubation period is longer in Ae. albopictus than in Ae. aegypti mosquitoes (17). Transmission of Zika virus may also involve mosquitoes of other species such as those of the genera Anopheles and Culex; the virus had been detected in An. coustani and Cx. perfuscus mosquitoes from Senegal (18,19).

In February 2016, China recorded its first case of Zika virus infection in Jiangxi Province; the case was confirmed to have been caused by virus imported from Venezuela (20). Since then, 13 cases caused by imported Zika virus have been reported from several provinces (21); no evidence of autochthonous transmission has been found. In China, Ae. aegypti mosquitoes are found only in small areas of southern China, including Hainan Province and small portions of Yunnan and Guangdong Provinces (22). The predominant mosquitoes across China, especially in cities, are Ae. albopictus and Cx. quinquefasciatus (23,24); Ae. albopictus mosquitoes are the primary vector of dengue virus (family Flaviviridae) (25). Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes are the primary vector for the causative organisms of St. Louis encephalitis, Rift Valley fever, lymphatic filariasis, and West Nile fever (26). The potential for Cx. pipiens mosquitoes to be Zika virus vectors (27) needs further confirmation. Because cases of Zika virus disease caused by imported virus have been reported in China, we investigated the potential vectors.

Mosquitoes

The Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention collected Ae. albopictus and Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes from different sites in the cities of Foshan (in 1981) and Guangzhou (in 1993) in Guangdong Province. In 2005, the China Center for Disease Control and Prevention collected Ae. aegypti mosquitoes from the city of Haikou in Hainan Province. All mosquitoes were maintained under standard insectary conditions of 27 ± 1°C, 70%–80% relative humidity, and a light:dark cycle of 16 h:8 h. To obtain enough individuals for the experiments, we collected eggs from mosquitoes of all 3 species and hatched them in dechlorinated water in stainless steel trays. The larvae (150–200/L water) were reared and fed daily with yeast and turtle food. Pupae were put into 250-mL cups and placed in the microcosm (20 cm × 20 cm × 35 cm cage covered with nylon mesh) until they emerged. Adults were kept in the microcosms and given 10% glucose solution ad libitum.

Zika Virus

Zika virus (GenBank accession no. KU820899.2), provided by the Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, was originally isolated from a patient in China in February 2016 and classified as the Asian lineage (28,29). The virus had been passaged once via intracranial inoculation of suckling mice and twice in C6/36 cells. In the laboratory at Southern Medical University (Guangzhou, China), C6/36 cells were infected by virus stocks with a multiplicity of infection of 1 and left to grow at 28°C for 5–7 days. The cells were suspended and separated into an aliquot and stored at −80°C. The frozen virus stock (3.28 ± 0.15 log10 copies/μL) was passaged once through C6/36 cells before the mosquitoes were infected. The fresh virus suspension (5.45 ± 0.38 log10 copies/μL) was used to prepare the blood meal.

Infection of Mosquitoes

We transferred 5–7-day-old female Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus, and Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes to 500-mL cylindrical cardboard containers covered with mesh, where they were starved for 24–48 h. The infectious blood meal was prepared by mixing defibrinated sheep blood (Solarbio, Beijing, China) with fresh virus suspension at a ratio of 1:2. The blood meal was warmed to 37°C and transferred into a Hemotek blood reservoir unit (Discovery Workshops, Lancashire, UK). Mosquitoes were then fed by using the Hemotek blood feeding system. Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to detect the virus concentration (copy level) in the blood meal before and after feeding. After 30 min of exposure to the infectious blood meal, mosquitoes were anesthetized with diethyl ether. Fully engorged females were transferred to 250-mL paper cups covered with net (10–15 mosquitoes/cup). The infected mosquitoes were provided with 10% glucose and maintained in an HP400GS incubator (Ruihua, Wuhai, China) at 28°C, 80% relative humidity, and a light:dark cycle of 16 h:8 h. The experiments were conducted according to standard procedures in a Biosafety Level 2 laboratory.

Zika Virus Infection in Whole Mosquitoes

To determine Zika virus infections in Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus and Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes, we selected 18–30 mosquitoes at postinfection days (dpi) 0 (same day as blood meal), 4, 7, 10, and 14. Each mosquito was placed in 50 μL TRIzol (Ambion, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and homogenized in a tissue grinder (Kontes, Vineland, NJ, USA). Total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol of TRIzol reagent and dissolved in 20 μL RNase-free water.

Zika virus cDNA synthesis reaction was performed by using the GoScript Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Total RNA and 10 μM Zika virus reverse primer (3′ untranslated region: 5′-ACCATTCCATTTTCTGGC-3′) were incubated, and cDNA was synthesized according to the procedure.

The nonstructural protein 1 (NS1) primers of Zika virus were designed by NCBI/Primer-BLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/index.cgi?LINK_LOC=BlastHome), which was selective for 296-bp nucleotide (forward: 5′-ACCCAAGTCTTTAGCTGGGC-3′; and reverse: 5′-CTGGTTCTTTCCTGGGCCTT-3′). The following PCR conditions were used: 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 7 min. The PCR products were examined by use of 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The target fragment was cloned into pMD18-T vector (Takara, Dalian, China) and sequenced.

Quantification of Zika Virus in Mosquitoes

The viral genome in the Zika virus–positive mosquitoes was determined by using absolute qRT-PCR. First, we constructed the standard. A 141-bp fragment across capsid and propeptide regions of Zika virus was amplified by specific primers (forward: 5′-GGAGAAG AAGAGACGAGGCG-3′; and reverse: 5′-GATATGGCCTCCCCAGCATC-3′) and cloned into pMD18-T vector. After sequencing, the recombinant plasmid was linearized by EcoR I. The concentration of plasmid was detected by NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). A standard curve (linear curve slope −3.447, Y intercept 38.312, R2 1, amplification efficiency 95.029) was generated from a range of serial 10-fold dilutions of the plasmid (6.23 × 102–6.23 × 107 copies/μL).

Each 20 μL of qRT-PCR was amplified by a 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) under the following conditions: 1 cycle at 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min; 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 1 min. Zika virus RNA copies from each sample were quantified by comparing cycle threshold value with the standard curve. The efficiency of this qRT-PCR system was evaluated by using blank control, uninfected C6/36 cells, C6/36 cells infected with Zika virus or DENV, and mosquitoes infected with Zika virus or DENV; the result displayed that its minimum detecting amount is 6.23 copies/μL of Zika virus and that the specificity is 100%.

Zika Virus Infection in Mosquito Tissues

To further analyze Zika virus tropisms and vector competence in Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus, and Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes, we infected another batch of mosquitoes with Zika virus and then dissected the midgut, head, and salivary glands of each mosquito at dpi 0, 4, 7, 10, and 14 by using 18–30 mosquitoes per time point. The legs and wings of mosquitoes were removed and placed into cold phosphate-buffered saline. Each tissue was dissected and washed 3 times in phosphate-buffered saline and transferred to 50 μL TRIzol (30). Following the above-mentioned procedure, we extracted total RNA, and the NS1 region of Zika virus from samples was detected by RT-PCR. The viral RNA copies from the positive samples were quantified by qRT-PCR. For those mosquitoes with Zika virus–negative midguts by RT-PCR and qRT-PCR, which we considered to be uninfected, we did not further analyze the heads and salivary glands. Vector competence of mosquitoes of 3 species was evaluated by calculating infection rate (no. infected midguts/no. tested midguts), dissemination rate (no. infected heads/no. infected midguts), transmission rate (no. infected salivary glands/no. infected midguts), and population transmission rate (no. infected salivary glands/no. tested mosquitoes).

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Logistic regression was used to compare the infection, dissemination, and transmission rates for different mosquito species at the same time or for the same species of mosquito at different times. p value significance was corrected by Bonferroni adjustments. The Zika virus RNA copy levels were log-transformed and then compared among mosquitoes of different species at the same time or among mosquitoes of the same species at different times by using post hoc Tukey honest significant difference tests.

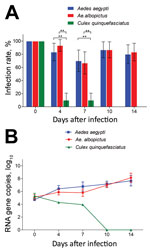

Zika Virus Infection of and Replication in Mosquitoes

After the 414 mosquitoes (138 of each of the 3 species) had ingested the infectious blood meal (dpi 0), RT-PCR indicated that all were Zika virus positive (Figure 1, panel A). The high proportion of mosquitoes infected with Zika virus was observed for Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes at dpi 4, 7, 10, and 14 (Figure 1, panel A). Infection rates were similar for Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes at all time points (z = 1.169, −0.277, 0.0001, 0.333; p>0.05) (Figure 1, panel A). However, at dpi 4 and 7, the infection rate for Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes was significantly lower than that for Ae. aegypti mosquitoes (z = −4.924, −4.186; p<0.01) and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes (z = −1.169, −4.007; p<0.01) (Figure 1, panel A). After dpi 7, no Zika virus was detected in the midgut of Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes (Figure 1, panel A).

The amount of Zika virus from the mosquitoes with midgut infection was further tested by qRT-PCR. The trend for mean Zika virus copies in Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes was an increase with time after infection, but that for Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes was a decrease (Figure 1, panel B). For Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, Zika virus copies increased quickly from dpi 0 to 4 (p<0.05 by Tukey honest significant difference test), then increased gradually. For Ae. albopictus mosquitoes, the trend for copy levels of Zika virus was similar to that for Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, but levels were slightly lower before dpi 7 (p<0.05). However, the copy levels were the same for mosquitoes of the 2 species at dpi 10 and 14 (p>0.05). For Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes, the virus copy levels were low before dpi 7 and totally diminished afterward (Figure 1, panel B).

Vector Competence of Mosquitoes after Oral Challenge

The infection, dissemination, and transmission rates for Zika virus were assessed by detecting infection status of mosquito midguts, heads, and salivary glands. Another 414 mosquitoes (138 from mosquitoes of each species) were infected by Zika virus, and the midguts were measured; the overall infection rates were 89.86% for Ae. aegypti, 87.68% for Ae. albopictus, and 15.94% for Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes (Table). At dpi 0, 100% of midguts were infected because of the undigested blood meal containing the virus, while no virus appeared in other tissues. High infection rates were maintained in Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes during the experimental period; no significant difference between Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes was found at dpi 4, 7, and 10 (z = 1.706, 1.777, 0.401; p>0.05) (Figure 2, panel A). At dpi 14, the infection rate for Ae. albopictus was higher than that for Ae. aegypti mosquitoes (z = 1.971; p = 0.04873). Compared with the infection rates for Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes, that for Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes was significantly lower at dpi 4 (z = −5.081, −4.539; p<0.01) and 7 (z = −4.682, −4.264; p<0.01), and no midguts were positive for Zika virus at dpi 10 and 14 (Figure 2, panel A).

The dissemination of Zika virus in the heads of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes started from dpi 4 and increased rapidly up to 100% after dpi 7 (Figure 2, panel B). The spread of Zika virus in the heads of Ae. albopictus mosquitoes was first detected at dpi 7, and the rate was lower than that for Ae. aegypti mosquitoes at the same time point (z = −3.832; p<0.05) (Figure 2, panel B). Peak dissemination occurred during dpi 4–7 for Ae. aegypti (z = 4.344; p<0.001) and 7–10 for Ae. albopictus (z = 3.543; p<0.001) mosquitoes. Overall, Zika virus infection was disseminated in 73.39% of midgut-infected Ae. aegypti mosquitoes but only 42.15% of midgut-infected Ae. albopictus mosquitoes (Table). Zika virus was not detected in the head tissues of Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes.

For Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, the detection of Zika virus in salivary glands was consistent with that in heads (Figure 2, panel C). Transmission of Zika virus by Ae. albopictus mosquitoes (which began at dpi 10 and increased to 68.97% at dpi 14) was lower at dpi 14 than that for Ae. aegypti mosquitoes at the same time (z = −3.561, −2.550; p<0.05) (Figure 2, panel C). A significant difference in transmission was detected during dpi 4–7 (z = 4.847; p<0.001) for Ae. aegypti and dpi 10–14 (z = 4.847; p = 0.0116) for Ae. albopictus mosquitoes. Zika virus was detected in the salivary glands of 78 (62.90%) midgut-infected Ae. aegypti and 29 (23.97%) midgut-infected Ae. albopictus mosquitoes. Furthermore, the population transmission rates of Zika virus were 56.52% for Ae. aegypti, 21.01% for Ae. albopictus, and 0% for Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes (Table).

The amount of Zika virus in mosquito midguts, heads, and salivary glands was measured by qRT-PCR. The Zika virus copies (log10) in midguts of Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus, and Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes did not differ significantly at dpi 0 (p>0.05). For Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, the Zika virus copies (log10) of midguts at dpi 4 were rapidly raised to 5.96 ± 0.92, which was higher than that at dpi 0 (5.00 ± 0.34) (p<0.05). Levels then increased continuously over time and reached 6.82 ± 0.47 at dpi 14 (Figure 3, panel A). For Ae. albopictus mosquitoes, the trend of increasing mean Zika virus copies was slow before dpi 7 and significantly lower than that for Ae. aegypti at the same time (p<0.05). After that, the growth of Zika virus became rapid and the Zika virus copies (log10) at dpi 14 reached 7.20 ± 0.48, which exceeded that in Ae. aegypti mosquitoes (p<0.05) (Figure 3, panel A). However, the amount of Zika virus continued to decrease in Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquito midguts after infection (Figure 3, panel A).

The number of Zika virus RNA copies (log10) in heads of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes continually increased from dpi 4 (4.97 ± 0.45) to 14 (6.19 ± 0.46) but remained stable for Ae. albopictus mosquitoes from dpi 7 (4.82 ± 0.43) to 10 (4.82 ± 0.64) and then reached 6.95 ± 0.81 at dpi 14 (Figure 3, panel B). At dpi 10, the number of virus copies in Ae. aegypti mosquitoes was higher than that in Ae. albopictus mosquitoes, whereas levels inverted at dpi 14 (p<0.05) (Figure 3, panel B). The trend of Zika virus in salivary glands was similar to that in the heads of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes. Compared with the Zika virus copies (log10) at dpi 0 (0), the value (5.54 ± 0.52) was apparently higher at dpi 14 (p<0.05) (Figure 3, panel C). Zika virus was detected in the salivary glands of Ae. albopictus mosquitoes during dpi 10–14, and the value at dpi 14 (6.19 ± 1.10) was higher than that at dpi 10 (4.92 ± 0.85). Furthermore, the number of virus copies in Ae. albopictus mosquitoes was higher than that in Ae. aegypti mosquitoes at dpi 14 (p<0.05) (Figure 3, panel C).

Because of the absence of vaccines and specific treatment, the major approach to prevention and control of Zika virus disease is vector control (31). Identification of the mosquito species that could transmit Zika virus and determination of the extrinsic incubation period of Zika virus will provide a guide for vector control. In this study, we demonstrated experimentally that Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes in China possess the ability to transmit Zika virus, whereas Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes were not able to transmit the virus under our laboratory conditions.

Our results demonstrate that Ae. aegypti mosquitoes could serve as vectors to spread Zika virus in China and that Ae. aegypti mosquitoes were better vectors than Ae. albopictus mosquitoes because transmission rate was higher and extrinsic incubation period was shorter for the former. The strong vector competence of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes could be associated with Zika virus rapid reproduction in the midgut during dpi 0–4, which enabled the viral particles to easily overcome the midgut barrier and be released into the hemolymph cavity and invade the salivary gland (32). Our findings are consistent with those for Ae. aegypti mosquitoes from Singapore and Italy (12,17). Although the distribution of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes is very limited in southern China, ranging from latitude 22°N to 25°N (33), the higher susceptibility of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes for Zika virus required the authorities in China to pay close attention to local epidemics of Zika virus in these regions.

Under the same experimental conditions, the whole-mosquito infection rates and midgut infection rates for Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti mosquitoes were similar, but the replication of Zika virus in midgut was slower for Ae. albopictus mosquitoes. The dissemination and transmission of Asian genotype Zika virus by Ae. albopictus mosquitoes in China started on 7 and 10 dpi, respectively, which indicated lower vector competence than that for Ae. albopictus mosquitoes from Singapore infected with East African genotype Zika virus from Uganda but higher than that for Ae. albopictus mosquitoes from the Americas infected with Asian genotype Zika virus from New Caledonia (13,34). Although the extrinsic incubation period was longer for Ae. albopictus than for Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, Ae. albopictus mosquitoes are widely distributed in China, especially in Guangdong Province, where dengue was often epidemic (35). Moreover, Ae. albopictus mosquito density and survival time has increased with urbanization (36,37). Taken together, these findings indicate that Ae. albopictus mosquitoes can potentially become the primary vector for Zika virus in China and need attention in the vector control strategy.

Cx. quinquefasciatus are common blood-sucking mosquitoes in China, especially in southern cities, and are the vector of Western equine encephalitis virus (38). However, in this study, at dpi 0, all Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes had ingested the virus, but the infection rate and Zika virus copies gradually decreased and no virus was detected in any tissues after dpi 7. The few positive midgut samples before dpi 7 could have resulted from an undigested blood meal because Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes are larger and might take more blood than Aedes mosquitoes. Our results illustrate that Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes in China are not able to transmit Zika virus, a finding that is consistent with the Zika virus susceptibility of Cx. pipiens mosquitoes from Iowa, USA, and Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (15,39). However, our results contradict those of Guo et al., which indicated that Cx. p. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes are potential Zika virus vectors in China (40). These contradictory results might come from different experimental conditions, virus strains, or mosquito species and need more study.

In our study, Zika virus from C6/36 cells or infected mosquitoes was sensitively and specifically identified by qRT-PCR. We used qRT-PCR to detect virus copies because the Zika virus strain isolated from the patient who imported the virus into China can infect C6/36, Aag2, and Vero cells but did not show obvious cytopathic effect, which could be associated with the patient’s mild clinical signs. Furthermore, previous research proved that the viral copies calculated by qPCR were consistent with the PFU detected by plaque assay (41). Although passage of the Zika virus we used in C6/36 cells was relatively low, the preliminary result demonstrated the highest virus reproduction in C6/36 cells compared with Aag2 and Vero cells.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that in China, Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes are susceptible to Zika virus, whereas Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes are not able to transmit the imported Zika virus. Comparatively, the vector competence of Ae. albopictus mosquitoes is inferior to that of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, but considering their wide distribution, Ae. albopictus mosquitoes might become the primary vector for Zika virus in China. These updated findings can be used for Zika virus disease prevention and vector control strategy.

Ms. Liu is a PhD candidate in the School of Public Health, Southern Medical University. Her research interest is in the prevention and control of mosquitoborne diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ping Zeng for helping with data analyses.

This study was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1200500), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (81371845, 81420108024), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2013B051000052, 2014A030312016), and the US National Institutes of Health (R01AI083202, D43 TW009527).

References

- Howard CR. Aedes mosquitoes and Zika virus infection: an A to Z of emergence? Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5:e16. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dick GWA, Kitchen SF, Haddow AJ. Zika virus. I. Isolations and serological specificity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1952;46:509–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Paixão ES, Barreto F, Teixeira MG, Costa MC, Rodrigues LC. History, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations of Zika: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:606–12. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, Powers AM, Kool JL, Lanciotti RS, et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2536–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cao-Lormeau VM, Blake A, Mons S, Lastère S, Roche C, Vanhomwegen J, et al. Guillain-Barré Syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: a case-control study. Lancet. 2016;387:1531–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Victora CG, Schuler-Faccini L, Matijasevich A, Ribeiro E, Pessoa A, Barros FC. Microcephaly in Brazil: how to interpret reported numbers? Lancet. 2016;387:621–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Petersen LR. Zika virus and birth defects—reviewing the evidence for causality. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1981–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Countries and territories with active local Zika virus transmission [cited 2016 Sep 8]. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/world-map-areas-with-zika

- Jang HC, Park WB, Kim UJ, Chun JY, Choi SJ, Choe PG, et al. First imported case of Zika virus infection into Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:1173–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- De Smet B, Van den Bossche D, van de Werve C, Mairesse J, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Michiels J, et al. Confirmed Zika virus infection in a Belgian traveler returning from Guatemala, and the diagnostic challenges of imported cases into Europe. J Clin Virol. 2016;80:8–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Emergency Committee on Zika virus and observed increase in neurological disorders and neonatal malformations [cited 2016 Jul 20]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/ news/statements/2016/1st-emergency-committee-zika/en/

- Li MI, Wong PS, Ng LC, Tan CH. Oral susceptibility of Singapore Aedes (Stegomyia) aegypti (Linnaeus) to Zika virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1792. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wong PS, Li MZ, Chong CS, Ng LC, Tan CH. Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse): a potential vector of Zika virus in Singapore. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2348. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Diagne CT, Diallo D, Faye O, Ba Y, Faye O, Gaye A, et al. Potential of selected Senegalese Aedes spp. mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) to transmit Zika virus. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:492. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Aliota MT, Peinado SA, Osorio JE, Bartholomay LC. Culex pipiens and Aedes triseriatus mosquito susceptibility to Zika virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1857–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Grard G, Caron M, Mombo IM, Nkoghe D, Mboui Ondo S, Jiolle D, et al. Zika virus in Gabon (Central Africa)—2007: a new threat from Aedes albopictus? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2681. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Di Luca M, Severini F, Toma L, Boccolini D, Romi R, Remoli ME, et al. Experimental studies of susceptibility of Italian Aedes albopictus to Zika virus. Euro Surveill. 2016;21:30223. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Diallo D, Sall AA, Diagne CT, Faye O, Faye O, Ba Y, et al. Zika virus emergence in mosquitoes in southeastern Senegal, 2011. PLoS One. 2014;9:e109442. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ayres CFJ. Identification of Zika virus vectors and implications for control. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:278–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Liu L, Wu W, Zhao X, Xiong Y, Zhang S, Liu X, et al. Complete genome sequence of Zika virus from the first imported case in mainland China. Genome Announc. 2016;4:e00291–16. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhang Y, Chen W, Wong G, Bi Y, Yan J, Sun Y, et al. Highly diversified Zika viruses imported to China, 2016. Protein Cell. 2016;7:461–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang G, Zhang H, Cao X, Zhang X, Wang G, He Z, et al. Using GARP to predict the range of Aedes aegypti in China. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2014;45:290–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wu F, Liu Q, Lu L, Wang J, Song X, Ren D. Distribution of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in northwestern China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:1181–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhao M, Dong Y, Ran X, Guo X, Xing D, Zhang Y, et al. Sodium channel point mutations associated with pyrethroid resistance in Chinese strains of Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:369. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhao H, Zhang FC, Zhu Q, Wang J, Hong WX, Zhao LZ, et al. Epidemiological and virological characterizations of the 2014 dengue outbreak in Guangzhou, China. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156548. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Samy AM, Elaagip AH, Kenawy MA, Ayres CF, Peterson AT, Soliman DE. Climate change influences on the global potential distribution of the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus, vector of West Nile virus and lymphatic filariasis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163863. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Franca RF, Neves MH, Ayres CF, Melo-Neto OP, Filho SP. First International Workshop on Zika Virus Held by Oswaldo Cruz Foundation FIOCRUZ in Northeast Brazil March 2016 - A Meeting Report. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004760. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dong XJ, Sun JM, Lou LQ, Zhu ZH, Zhu LB, Lou T. [Survey of the third Zika virus disease case in the mainland of China] [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2016;37:597–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Deng C, Liu S, Zhang Q, Xu M, Zhang H, Gu D, et al. Isolation and characterization of Zika virus imported to China using C6/36 mosquito cells. Virol Sin. 2016;31:176–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhang M, Zheng X, Wu Y, Gan M, He A, Li Z, et al. Quantitative analysis of replication and tropisms of Dengue virus type 2 in Aedes albopictus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:700–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Possas C. Zika: what we do and do not know based on the experiences of Brazil. Epidemiol Health. 2016;38:e2016023. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Franz AW, Kantor AM, Passarelli AL, Clem RJ. Tissue barriers to arbovirus infection in mosquitoes. Viruses. 2015;7:3741–67. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Li CX, Kaufman PE, Xue RD, Zhao MH, Wang G, Yan T, et al. Relationship between insecticide resistance and kdr mutations in the dengue vector Aedes aegypti in Southern China. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:325. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chouin-Carneiro T, Vega-Rua A, Vazeille M, Yebakima A, Girod R, Goindin D, et al. Differential susceptibilities of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus from the Americas to Zika virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004543. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Luo L, Li X, Xiao X, Xu Y, Huang M, Yang Z. Identification of Aedes albopictus larval index thresholds in the transmission of dengue in Guangzhou, China. J Vector Ecol. 2015;40:240–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Manica M, Filipponi F, D’Alessandro A, Screti A, Neteler M, Rosà R, et al. Spatial and temporal hot spots of Aedes albopictus abundance inside and outside a south European metropolitan area. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004758. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Li Y, Kamara F, Zhou G, Puthiyakunnon S, Li C, Liu Y, et al. Urbanization increases Aedes albopictus larval habitats and accelerates mosquito development and survivorship. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3301. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang Z, Zhang X, Li C, Zhang Y, Xing D, Wu Y, et al. Vector competence of five common mosquito species in the People’s Republic of China for Western equine encephalitis virus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:605–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fernandes RS, Campos SS, Ferreira-de-Brito A, Miranda RM, Barbosa da Silva KA, Castro MG, et al. Culex quinquefasciatus from Rio de Janeiro is not competent to transmit the local Zika virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004993. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guo XX, Li CX, Deng YQ, Xing D, Liu QM, Wu Q, et al. Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus: a potential vector to transmit Zika virus. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5:e102. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fortuna C, Remoli ME, Di Luca M, Severini F, Toma L, Benedetti E, et al. Experimental studies on comparison of the vector competence of four Italian Culex pipiens populations for West Nile virus. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:463. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Table

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 23, Number 7—July 2017

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Xiao-Guang Chen, Department of Pathogen Biology, School of Public Health, Southern Medical University, 1038 Sha Tai North Rd, Guangzhou, China

Top