Volume 26, Number 4—April 2020

About the Cover

Different Angles, Changing Perspectives

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

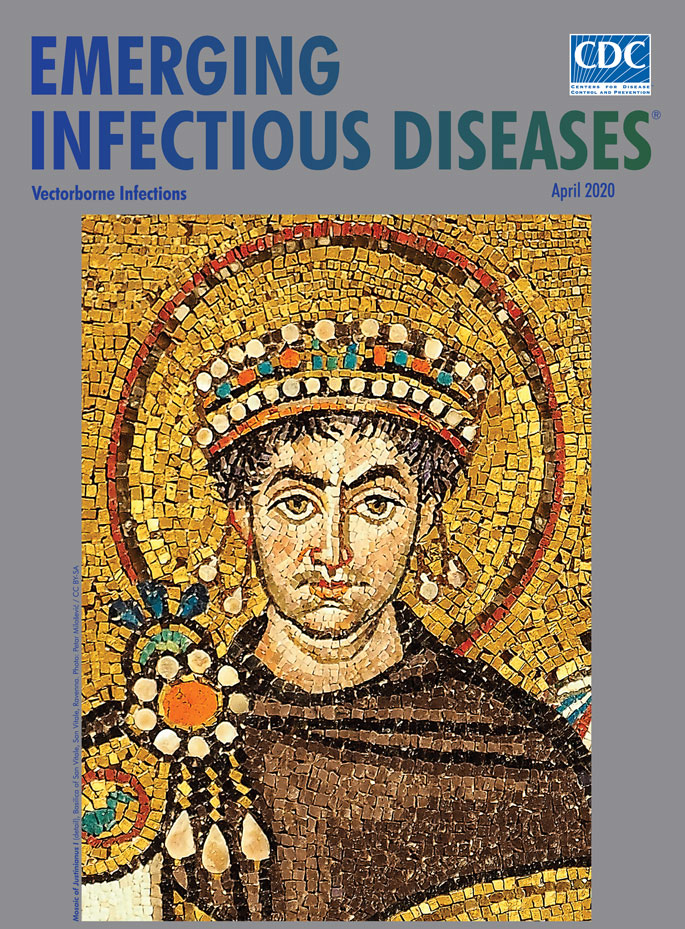

This month’s cover image is a detail from the mosaic of the Emperor Justinian and his court in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. Ancient Roman mosaics such as these, typically created by unknown artisans, may be found in private villas and public buildings and provide durable, vivid documentation of ancient Roman life. According to the Getty Museum, many of these intricate, detailed works served as floors in numerous villas and were “designed to be viewed from different angles and to change as your perspective moves.”

The artisans who assembled these mosaics combined thousands of mostly square tiles made from limestone, marble, glass, ceramic, and sometimes precious stones. They arranged these tiles like a complex jigsaw puzzle and affixed them into position with mortar.

This particular mosaic, viewed as a whole (Figure), depicts the emperor in a ceremonial purple robe with a golden halo, a traditional rendering that symbolizes the importance of the Roman emperor in the Christian church and sets him apart from the more plainly dressed figures surrounding him, further emphasizing the authority of the emperor and his reign. The soldiers to his right and clergy on his left affirm his stature as the center of church and state. The mosaic, which imparts no sense of motion or depth, most likely documents a ceremonial gathering or formal event, perhaps in the same manner that a modern “photo op” might.

Justinian saw himself as the “defender of the faith,” with a mandate to spread that faith throughout the empire. That power, however, did not allow him to escape what historians have called the Plague of Justinian, an outbreak now thought to be due to Yersinia pestis, that left him at the brink of death for several weeks, though he did survive. In modern times, scientific progress has enabled clinicians to diagnose suspected cases of plague sooner and administer life-saving treatments with antimicrobial drugs.

Bibliography

- Cartwright M. Roman mosaics. Ancient history encyclopedia [cited 2020 Mar 13]. https://www.ancient.eu/article/498/roman-mosaics

- Harbeck M, Seifert L, Hänsch S, Wagner DM, Birdsell D, Parise KL, et al. Yersinia pestis DNA from skeletal remains from the 6th century AD reveals insights into Justinianic Plague. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:

e1003349 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Horgan J. Justinian’s plague (541–542

ce ). Ancient history encyclopedia. [cited 2020 Feb 26]. https://www.ancient.eu/article/782/justinians-plague-541-542-ce - Mordechai L, Eisenberg M, Newfield TP, Izdebski A, Kay JE, Poinar H. The Justinianic Plague: An inconsequential pandemic? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:25546–54. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Perry RD, Fetherston JD. Yersinia pestis—etiologic agent of plague. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:35–66. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rosen W. Justinian’s flea: plague, empire, and the birth of Europe, New York: Penguin; 2007. p. 308–9

- Stephan A. A brief introduction to Roman mosaics: 15 key facts about this quintessential Roman art form, from how they were made to who once owned them. Art & Archives. The Getty. [cited 2020 Mar 3]. https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/a-brief-introduction-to-roman-mosaics

Figure

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: March 17, 2020

Related Links

Table of Contents – Volume 26, Number 4—April 2020

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Byron Breedlove, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Rd NE, Mailstop US12-4, Atlanta, GA 30329-4027, USA

Top