Volume 31, Number 2—February 2025

About the Cover

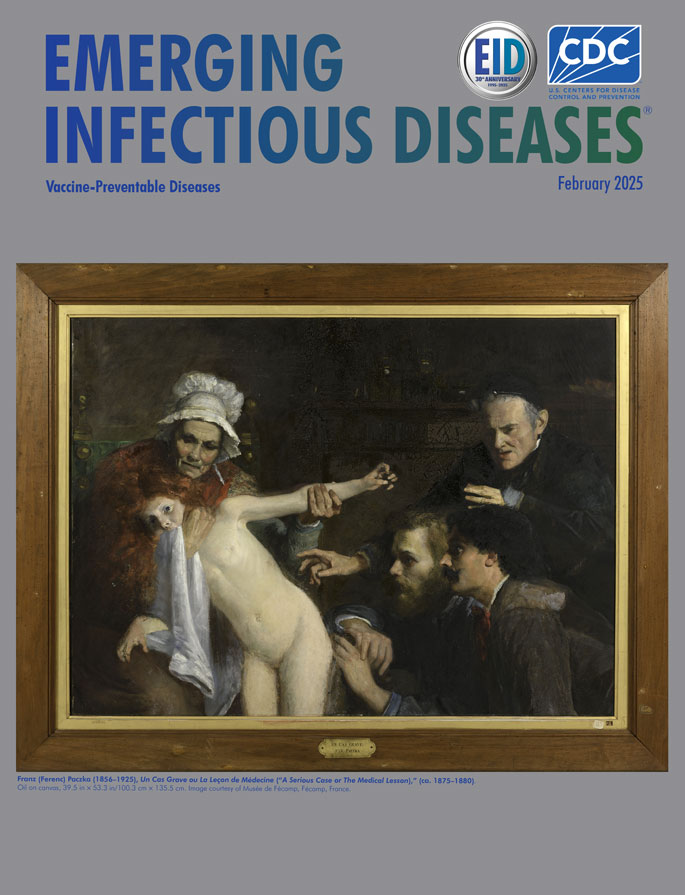

A Pictorial Human Case of “Furious Rabies”

Franz (Ferenc) Paczka (1856–1925), Un Cas Grave ou La Leçon de Médecine (A Serious Case or The Medical Lesson) (ca. 1875–1880). Oil on canvas, 39.5 in × 53.3 in/100.3 cm × 135.5 cm. Image courtesy of Musée de Fécamp, Fécamp, France.

Franz (Ferenc) Paczka was a Hungarian genre painter and portraitist who studied in Paris and Rome and exhibited a few paintings at the 1878 Paris Universal Exhibition, in the Austria-Hungary section. When Paczka left France to serve in the military in his native country, he had to sell his Parisian studio collection (1). On April 21, 1880, an anonymous donor offered one of his paintings, considered unfinished, “Un Cas Grave ou La Leçon de Médecine” (A Serious Case or The Medical Lesson), to the fledgling Musée de Fécamp, barely 2 weeks before its official inauguration. The painting is unusual, given that Paczka usually painted portraits or small groups in calm everyday settings. Instead, it represents 2 doctors examining an unclear skin lesion on the side of a young girl who has a towel in her mouth and seems to be suffering and agitated so that she has to be held still.

There was no record as to the medical condition affecting the girl depicted in the painting. One nefarious conjecture might be that this picture may have demoniac overtones, a hypothesis that may be supported by several elements and symbols, such as the girl’s red hair, the possible presence of a priest (with his skullcap and his black clothes) behind the doctors and the way he is pointing to the “mark,” and the wound that may represent “the devil’s mark.” Moreover, in 1850–1900, France experienced a revival of occultism, spiritualism, magic, astrology, and mysticism.

However, a recently found newspaper article describing the painting and published on February 6, 1954, in Le Progrès de Fécamp by its director Jules Rolland (under the pseudonym Gihères), reveals that the lesion the doctors are examining is a dog bite wound: “‘Un cas grave’: a large canvas by Paczka. Two doctors examine suspicious spots on the body of a girl bitten by a dog. The grandfather’s and grandmother’s attitudes are fairly conventional” (2). This useful indication, which at that time probably appeared on the work’s label, reveals an element for an interesting retrospective diagnosis and an alternative hypothesis on this painting’s meaning.

The bite mark in a rabies victim usually heals before the onset of symptoms. However, the presence of the bite mark/scar months later might depend on the severity of the bite, whether it was subsequently infected, or the bite’s location on the body. On the basis of that information and on the evident agitation of the young girl, we speculate that this painting represents a case of the encephalic form of rabies, known as furious rabies. The painting, preserved in Musée de Fécamp, predates Émile Roux’s first inoculation of a human with rabies vaccine in July 1885; it reveals the powerlessness of families and doctors in the face of such violent symptoms and, in case of rabies, the fatal diagnosis for the victim. Cases of the disease now called rabies were recorded during the classical antiquity period (3). In the 4th Century BCE, Aristotle described the disease in his History of Animals: “Dogs suffer from three diseases … of these, rabies produces madness, and when rabies develops in all animals that the dog has bitten… it kills them; and this disease kills the dogs too” (4).

Rabies is a zoonotic disease caused by viruses of the genus Lyssavirus, family Rhabdoviridae, order Mononegavirales. Viruses are transmitted by the saliva of the infected animal. Similar to the situation in France in the 1800s, dogs today remain the biggest concern for human rabies exposures globally, and in certain parts of the world, wildlife such as bats, foxes, jackals, mongooses, racoons, skunks, and others also transmit rabies (5). Rabies virus first enters in peripheral motor neurons and then passes to the central nervous system, causing signs and symptoms (5). Rabies can be exhibited in 2 forms—encephalitic (or furious) and paralytic—but the determining factors are not well known. Signs and symptoms depend on the form. The incubation period is 20–90 days after exposure. A short prodromal phase while the virus replicates in the dorsal root ganglia includes fever, pain, paraesthesia, pruritus, or a combination of those symptoms. In cases of furious rabies, a next acute neurologic phase is characterized by hyperactivity, confusion and agitation, hypersalivation, piloerection, hydrophobia, aerophobia resulting from electrolyte imbalance, dysphagia, hyperventilation, coordination disorders, hallucinations, and, finally, coma and death (5,6).

Primary prevention is based on animals’ vaccination to reduce the virus reservoirs. Because in most areas the primary reservoir is dogs, vaccination and elimination of stray dogs reduce virus circulation, as does dissemination of vaccine-containing bait for wild animals in rural areas. Progression to clinical disease can be prevented if wound care and postexposure prophylaxis by immunoglobulin and vaccination are administered rapidly after animal bite, thus sparing many people around the world from suffering the same fate as the young girl depicted by Paczka in his painting. Unfortunately, the therapeutic is not available everywhere.

Although Louis Pasteur developed the first effective rabies vaccines for humans in the 19th Century, today, the virus is still endemic among animals in some regions of the world (i.e., throughout Asia and Africa), and human rabies remains a serious public health challenge (6,7). Un Cas Grave ou La Leçon de Médecine is an example of how art can tell the history of medicine and focus on a health issue that is perhaps underestimated today.

Acknowledgment

We thank the team of Les Pêcheries, Musée de Fécamp: Aurélien Arnaud, Céline Magnan, Benjamin Loesel, and Quentin Panel.

Bibliography

- Hue C. Historique du musée de peinture et d'objets d'art de Fécamp. Fécamp, France; Memorial du Cauchois; 1880.

- Rolland J. “Le musée municipal: l’Histoire et l’Art y ont accumulé de véritables trésors, enviés des grands musées nationaux.” Le Progrès de Fécamp, 6 février 1954.

- Tarantola A. Four thousand years of concepts relating to rabies in animals and humans, its prevention and its cure. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2017;2:5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Aristotle . History of animals [translated by Peck AL, Balme DM, Gotthelf A]. London (UK), Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1965. P. 182–3.

- Fooks AR, Cliquet F, Finke S, Freuling C, Hemachudha T, Mani RS, et al. Rabies. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17091. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fooks AR, Banyard AC, Horton DL, Johnson N, McElhinney LM, Jackson AC. Current status of rabies and prospects for elimination. Lancet. 2014;384:1389–99. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pattnaik P, Mahal A, Mishra S, Alkhouri A, Mohapatra RK, Kandi V. Alarming rise in global rabies cases calls for urgent attention: current vaccination status and suggested key countermeasures. Cureus. 2023;15:

e50424 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Original Publication Date: January 22, 2025

Related Links

Table of Contents – Volume 31, Number 2—February 2025

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Antonio Perciaccante, Department of Medicine, Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Giuliano Isontina, “San Giovanni di Dio” Hospital, via Fatebenefratelli, 34 Goriza 34170, Italy

Top