Volume 8, Number 12—December 2002

Dispatch

Rat-to-Human Transmission of Cowpox Infection

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

We isolated Cowpox virus (CPXV) from the ulcerative eyelid lesions of a 14-year-old girl, who had cared for a clinically ill wild rat that later died. CPXV isolated from the rat (Rattus norvegicus) showed complete homology with the girl’s virus. Our case is the first proven rat-to-human transmission of cowpox.

A 14-year-old girl was admitted to the hospital with ulcerated nodules on her upper lip and her left lower eyelid and several molluscum-like-lesions on her right eyelids (Figure 1). She was feverish but otherwise in good health. Values of complete blood and differential counts were within normal limits. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 41 mm the first hour, and she was treated orally with ciprofloxacin. Within a few days the lesions on her eyelids developed into crater-like ulcers, which were surrounded by inflammatory tissue and were later covered by thick black crusts; and sedema and erythema developed on the right side of her face. At home she kept turtles, hamsters, guinea pigs, birds, ducks, cats, and a dog. She also cared for a clinically ill wild rat, which she had found 2 weeks before admission. After 6 days of care, the rat died and was buried. During the following 4 weeks, the ulcerated lesions on the girl’s face healed and left atrophic scars.

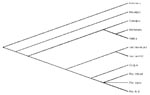

Routine virus isolation procedures from biopsies of the eyelid lesions in Vero cells showed the presence of Orthopoxvirus. Serum immunoglobulin (Ig) M antibodies to the viral isolate and to Vaccinia virus were detected upon admission. The virus was identified as Cowpox virus (CPXV) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequence analysis (PCR directed at the Orthopoxvirus fusion protein gene, as described by Chantrey et al.) (1). The rat, identified as Rattus norvegicus, was recovered for laboratory testing. CPXV was isolated from brain samples from the rat, and a swab was taken from its paw. Sequence analysis of the rat’s virus indicated complete homology with the girl’s virus. As shown in Figure 2, the sequence analysis clearly demonstrates that the virus was CPXV.

Human CPXV is a rare zoonosis, which is transmitted as a result of contact with animals.

Usually localized at the site of inoculation, CPXV lesions progress from a papule through vesiculation and pustulation into an ulcerative nodule, which is covered with an elevated border with a black eschar. Ulcera heal with scar formation. Differential clinical diagnosis of CPXV includes herpes virus infection, anthrax, and orf (caused by a Parapoxvirus). CPXV is almost always a self-limiting disease in immunocompetent hosts.

Although wild rodents are the reservoir hosts of CPXV (1), transmission to humans has only been described from accidental hosts such as infected cats, cows, and animals in zoos and circuses (2–4). Circumstantial evidence of rodents as source of infection has been reported in two human cases: one infection was associated with a suspected rat bite (5); the other infection was in a person who cared for a sick wild field mouse (6). Person-to-person transmission has not been reported.

Our case is the first proven wild rodent-to-human transmission. Serologic surveys have shown that CPXV is a widespread endemic infection in European wild rodents with the highest seroprevalence in bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus), wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus) and field voles (Microtus agretis) (1). Seroprevalence rates in rats are not available; therefore, whether rats might also be reservoir hosts or act as liaison (accidental) hosts is unclear. Since smallpox has not occurred naturally anywhere in the world since 1977, immunization with Vaccinia virus has been discontinued, which has led to a declined cohort immunity to orthopoxviruses including CPXV, and thus may result in an increased incidence of human CPXV infections (2,7). Physicians must be aware that zoonosis may not only be contracted from accidental hosts (e.g., cats and cows) but also directly from a primary natural reservoir (rodents).

Dr. Wolfs is an infectious diseases pediatrician at the Wihelmina Children’s Hospital, Utrecht, the Netherlands. His research intersts include HIV and the interaction between viral and bacterial infections.

References

- Chantrey J, Meyer H, Baxby D, Begon M, Bown KJ, Haxel SM, Cowpox: reservoir hosts and geographic range. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;122:455–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Willemse A, Egberink HF. Transmission of cowpox virus infection from domestic cat to man. Lancet. 1985;1:1515. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vestey JP, Yirrel DL, Aldridge RD. Cowpox/catpox infection. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:74–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Baxby D, Bennett M, Getty B. Human cowpox 1969–93: a review based on 54 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:598–607. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Postma BH, Diepersloot RJA, Niessen GJCM, Droog RP. Cowpox-virus-like infection associated with rat bite. Lancet. 1991;337:733–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lewis-Jones MS, Baxby D, Cefai C, Hart CA. Cowpox can mimic anthrax. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:625–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vestey JP, Yirrel DL, Aldridge RD. Cowpox/catpox infection. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:74–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 8, Number 12—December 2002

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Tom F.W. Wolfs, Dept. of Infectious Diseases, Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital/University Medical Center, KE04.133.1, PO Box 85090, 3508 AB Utrecht, the Netherlands; fax: 31-30 2505349,

Top