Volume 8, Number 4—April 2002

Perspective

Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Resistance: A Population Perspective

Figure

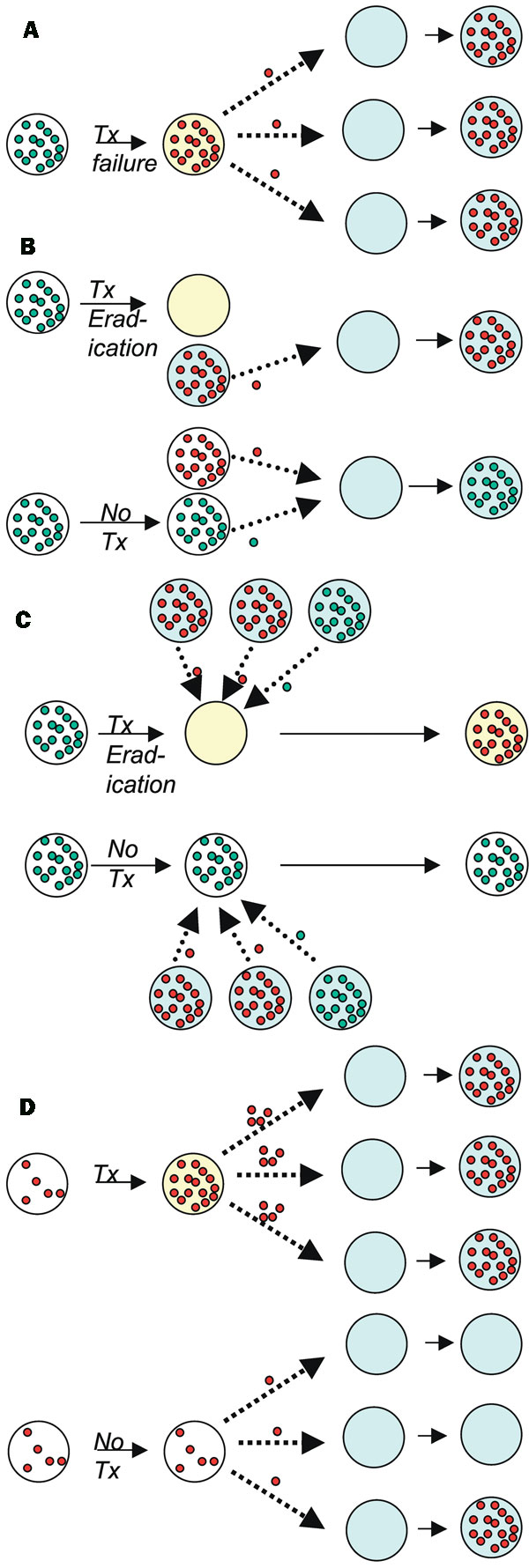

Figure. Four mechanisms by which antibiotic treatment can create selection for resistance in the population, showing direct effects—increased resistance in treated (yellow) vs. untreated (white) hosts, and indirect effects—increased resistance in others (turquoise) due to treatment of specific hosts. (A) Subpopulations (usually mutants) of resistant (red) bacteria are present in a host infected with a predominantly susceptible (green) strain; treatment fails, resulting in outgrowth of the resistant subpopulation, which can then be transmitted to other, susceptible hosts (turquoise). (B) Successful treatment of an individual infected with a susceptible strain reduces the ability of that host to transmit the infection to other susceptible hosts, making those hosts more likely to be infected by resistant pathogens than they would otherwise have been, and shifting the competitive balance toward resistant infections. (C) Treatment of an infection eradicates a population of susceptible bacteria carried (often commensally) by the host, making that host more susceptible to acquisition of a new strain. If the newly acquired strain has a high probability of being resistant (as in the context of an outbreak of a resistant strain), this can significantly increase the treated individual’s risk of carrying a resistant strain, relative to an untreated one. (D) Treatment of an infection in an individual who is already colonized (commensally) with resistant organisms may result in increased load of those organisms if competing flora (perhaps of another species) are inhibited—leading to increased shedding of the resistant organism and possibly to increased individual risk of infection with the resistant organism.