Volume 10, Number 5—May 2004

Research

Ring Vaccination and Smallpox Control

Figure 6

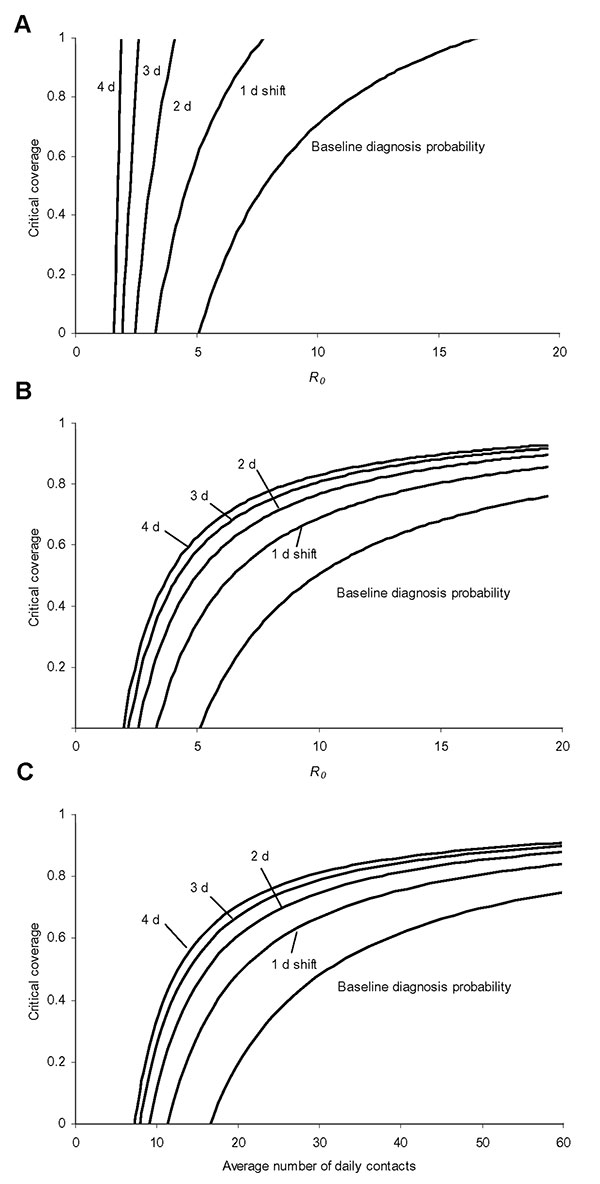

Figure 6. Here the critical vaccination coverage in the casual contact ring is shown as a function of the basic reproduction number R0 for different assumptions about the time it takes to diagnose infectious persons. A, for the baseline assumption, that diagnosis is very quick after the beginning of the infectious period, a low coverage is sufficient if R0 is 5, but for R0 around 10 the coverage has to be at least 70% for the intervention to be successful. If the probability of being diagnosed shifts to later days of the infectious period, the situation quickly gets out of control and vaccination can no longer curb the epidemic. In B, the same is shown with the difference that here we assume that vaccinated contacts are successfully monitored such that they can no longer produce any secondary infections, even if their vaccination was too late to prevent them from becoming infectious. In this case a later diagnosis is not that influential, but nevertheless, if R0 is 10, the vaccination coverage (or the percentage of contacts identified and monitored) must be at least 50% to guarantee success. In C, the critical coverage of the casual contact ring is shown as a function of the average number of contacts per day, again for the situation where vaccination is combined with monitoring of contacts. The average number of contacts was varied by varying the number of daily casual contacts. The effect is the similar to that of varying R0 through the transmission probability per contact as shown in B.