Volume 7, Number 2—April 2001

THEME ISSUE

4th Decennial International Conference on Nosocomial and Healthcare-Associated Infections

Prevention is Primary

Automated Methods for Surveillance of Surgical Site Infections

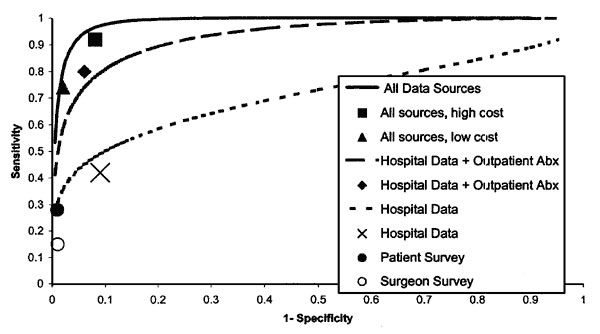

Figure

Figure. Performance of various methods for detection of postdischarge surgical site infections for 4,086 nonobstetric surgical procedures with no inpatient infection. Lines represent fitted receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for three logistic regression models, which differ by data sources available for generating probabilities. Points represent performance of four different recursive partitioning models and data from patient and physician surveys. For analyses limited to hospital data and outpatient antibiotic (Abx) dispensing data, the logistic regression model had equivalent performance to classification trees at the points shown. The fitted ROC curve falls below this point because most procedures clustered around a few discrete probabilities and limited data points cause approximation of the ROC curve to be less accurate. The recursive partitioning high-cost model accepts 15 false-positives at the margin to capture one true infection; the low-cost model accepts 5 false positives at the margin (24

References

- Haley RW, Culver DH, White JW, Morgan WM, Emori TG, Munn VP, The efficacy of infection surveillance and control programs in preventing nosocomial infections in US hospitals. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:182–205.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gaynes RP, Horan TC. Surveillance of nosocomial infections. In: C.G. Mayhall, editor. Hospital epidemiology and infection control. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 1999. Chapter 85.

- Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WL. Guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:247–78. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Emori TG, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Sartor C, Stroud LA, Gaunt EE, Accuracy of reporting nosocomial infections in intensive-care-unit patients to the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance system: a pilot study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1998;19:308–16. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sands K, Vineyard G, Platt R. Surgical site infections occurring after hospital discharge. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:963–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reimer K, Gleed G, Nicolle LE. The impact of postdischarge infection on surgical wound infection rates. Infect Control. 1987;8:237–40.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Manian FA, Meyer L. Comprehensive surveillance of surgical wound infections in outpatient and inpatient surgery. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1990;11:515–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Burns SJ. Postoperative wound infections detected during hospitalization and after discharge in a community hospital. Am J Infect Control. 1982;10:60–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Polk BF, Shapiro M, Goldstein P, Tager I, Gore-White B, Schoenbaum SC. Randomised clinical trial of perioperative cefazolin in preventing infection after hysterectomy. Lancet. 1980;1:437–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brown RB, Bradley S, Opitz E, Cipriani D, Pieczrka R, Sands M. Surgical wound infections documented after hospital discharge. Am J Infect Control. 1987;15:54–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Byrne DJ, Lynce W, Napier A, Davey P, Malek M, Cuschieri A. Wound infection rates: the importance of definition and post-discharge wound surveillance. J Hosp Infect. 1994;26:37–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Holtz TH, Wenzel RP. Postdischarge surveillance for nosocomial wound infection: a brief review and commentary. Am J Infect Control. 1992;20:206–13. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sherertz RJ, Garibaldi RA, Marosok RD. Consensus paper on the surveillance of surgical site infections. Am J Infect Control. 1992;20:263–70. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Owings MF, Kozak LJ. Ambulatory and inpatient procedures in the United States, 1996. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 1999;13:139.

- Lawrence L, Hall MJ. National Center for Health Statistics. 1977 Summary: National Hospital Survey. Adv Data. 1999;308:1–16.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Garibaldi RA, Cushing D, Lerer T. Risk factors for postoperative infection. Am J Med. 1991;91:158S–63S. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Haynes SR, Lawler PG. An assessment of the consistency of ASA physical status classification allocation [see comments]. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:195–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Salemi C, Anderson D, Flores D. American Society of Anesthesiology scoring discrepancies affecting the National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System: surgical-site-infection risk index rates. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1997;18:246–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wenzel R, Osterman C, Hunting K, Galtney J. Hospital-acquired infections. I. Surveillance in a university hospital. Am J Epidemiol. 1976;103:251–60.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Broderick A, Motomi M, Nettleman M, Streed S, Wenzel R. Nosocomial infections: validation of surveillance and computer modeling to identify patients at risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131:734–42.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hirschhorn L, Currier J, Platt R. Electronic surveillance of antibiotic exposure and coded discharge diagnoses as indicators of postoperative infection and other quality assurance measures. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1993;14:21–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yokoe DS, Shapiro M, Simchen E, Platt R. Use of antibiotic exposure to detect postoperative infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1998;19:317–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yokoe DS. Enhanced methods for inpatient surveillance of surgical site infections following cesarean delivery [Abstract S-T3-03]. Fourth Decennial International Conference on Healthcare-Associated and Nosocomial Infections. 2000 Mar 5-9; Atlanta, GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Sands K, Vineyard G, Livingston J, Christiansen C, Platt R. Efficient identification of postdischarge surgical site infections using automated medical records. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:434–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sands K, Yokoe D, Hooper D. Tully, Platt R. Multi-institutional comparison of surgical site infection surveillance by screening of administrative and pharmacy data [Abstract M35]. Society of Healthcare Epidemiologists, Annual meeting; Apr 18-20 1999; San Francisco.

- Yokoe DS, Christiansen C, Sands K, Platt R. Efficient identification of postpartum infections occurring after discharge [Abstract P-T1-20]. 4th Decennial International Conference on Healthcare-associated and Nosocomial Infections. 2000 Mar 5-9; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Von Korff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K. A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:197–203. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fishman P, Goodman M, Hornbrook M, Meenan R, Bachman D, O'Keefe-Rosetti M. Risk adjustment using automated pharmacy data: a global Chronic disease score. 2nd International Health Economic Conference, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, 1999.

- Clark DO, Von Korff M, Saunders K, Baluch WM, Simon GE. A chronic disease score with empirically derived weights. Med Care. 1995;33:783–95. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kaye KS, Sands K, Donahue JG, Chan A, Fishman P, Platt R. Preoperative drug dispensing predicts surgical site infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:57–64. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

¹The CDC Eastern Massachusetts Prevention Epicenter includes Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Massachusetts, CareGroup, Children's Hospital, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Partners Healthcare System, Tufts Health Plan, and Harvard Medical School. Investigators include L. Higgins, J. Mason, E. Mounib, C. Singleton, K. Sands, K. Kaye, S. Brodie, E. Perencevich, J. Tully, L. Baldini, R. Kalaidjian, K. Dirosario, J. Alexander, D. Hylander, A. Kopec, J. Eyre-Kelley, D. Goldmann, S. Brodie, C. Huskins, D. Hooper, C. Hopkins, M. Greenbaum, M. Lew, K. McGowan, G. Zanetti, A. Sinha, S. Fontecchio, R. Giardina, S. Marino, J. Sniffen, E. Tamplin, P. Bayne, T. Lemon, D. Ford, V. Morrison, D. Morton, J. Livingston, P. Pettus, R. Lee, C. Christiansen, K. Kleinman, E. Cain, R. Dokholyan, K. Thompson, C. Canning, D. Lancaster.