Volume 15, Number 12—December 2009

Research

Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Hospital Infection Control Response to an Epidemic Respiratory Virus Threat

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

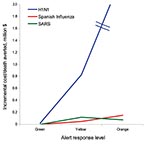

The outbreak of influenza A pandemic (H1N1) 2009 prompted many countries in Asia, previously strongly affected by severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), to respond with stringent measures, particularly in preventing outbreaks in hospitals. We studied actual direct costs and cost-effectiveness of different response measures from a hospital perspective in tertiary hospitals in Singapore by simulating outbreaks of SARS, pandemic (H1N1) 2009, and 1918 Spanish influenza. Protection measures targeting only infected patients yielded lowest incremental cost/death averted of $23,000 (US$) for pandemic (H1N1) 2009. Enforced protection in high-risk areas (Yellow Alert) and full protection throughout the hospital (Orange Alert) averted deaths but came at an incremental cost of up to $2.5 million/death averted. SARS and Spanish influenza favored more stringent measures. High case-fatality rates, virulence, and high proportion of atypical manifestations impacted cost-effectiveness the most. A calibrated approach in accordance with viral characteristics and community risks may help refine responses to future epidemics.

Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus is a new influenza virus of swine origin that was first detected in April 2009. Within 4 months of its appearance in Mexico, it had spread to >100 countries, with >200,000 confirmed cases globally, including >2,000 deaths (1). When the World Health Organization (WHO) raised its global influenza pandemic alert to phase 5 (imminent pandemic) on April 27, 2009, many countries followed suit and activated their pandemic preparedness plans, although this varied between countries. Many countries with direct experience of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak tended toward more stringent measures.

Singapore was one of the countries most affected by SARS and experienced a disproportionate impact of the spread of the disease in hospitals (2,3). A total of 98 healthcare workers in Singapore were infected with SARS, 6 of whom died (4). After the SARS experience, Singapore’s Ministry of Health (MOH) developed a pandemic influenza plan with several levels of response that correlated roughly with the WHO Pandemic Alert Response system (5). The Disease Outbreak Response System (DORSCON)-FLU system that MOH devised requires progressively higher levels of infection control in hospitals in addition to border screening, restrictions on visitors to hospitals, and community-based syndromic surveillance for acute febrile illnesses (Table 1).

In accordance with the progressive elevation of WHO pandemic alert levels, Singapore raised its own pandemic alert level to Yellow on April 27, 2009, and further elevated it to Orange 2 days later. At this level, all hospital staff were required to wear N95 masks when dealing with all patients. Patients were restricted to 1 registered and screened visitor, all medical and nursing student rotations and local medical conferences were cancelled, leave restrictions for healthcare workers (HCWs) were put in place, interhospital movement of patients and HCWs was banned, and further limitations were placed on elective surgery. These measures were aimed primarily at avoiding a repeat of the SARS epidemic where nosocomial transmission originated with patients whose SARS infections were undiagnosed in hospital, and because influenza may be contagious before symptoms develop in infected patients. In fact, nosocomial influenza has been well documented since the 1957 Asian influenza pandemic (6). Based on studies conducted primarily in the United States, it has been estimated that 1 nosocomial case of influenza in a pediatric unit can cost up to $7,500 (US) (7). A recent review (8) of 28 nosocomial outbreaks of seasonal influenza summarized the evidence for nosocomial transmission of influenza in hospitals with accompanying illness and death (8,9).

When it subsequently became apparent that the case-fatality rate for pandemic (H1N1) 2009 was much lower than previously thought, especially in settings of industrialized countries, the alert level in Singapore was lowered to Yellow on May 11, 2009, even as WHO moved to alert level 6 after the pandemic was declared.

The risks and impacts of an outbreak will no doubt depend on the transmissibility, virulence, and clinical severity of illness. Thus, the benefits of a high alert status response at the onset of an outbreak as a “safe rather than sorry” strategy is not unreasonable when faced with an unknown novel potentially lethal virus. Yet, on the other hand, preventive measures from a hospital perspective come with a price. Direct costs include activation as well as ongoing administrative, manpower, and logistic resources, such as use of enhanced personal protective equipment, as part of the alert response measures.

We made use of this unique opportunity to evaluate the real costs of our primary prevention interventions and their potential cost-effectiveness against different models of influenza virulence and transmissibility in a simulated outbreak in our 1,000-bed tertiary teaching hospital to understand the relative incremental cost per additional death averted at different alert status levels. The key variables that affected the cost-effectiveness ratio the most were identified and studied. The same analysis was subsequently repeated for a parallel 1,500-bed tertiary teaching hospital. Using the outcome variables of disease cases, deaths, and incremental cost per death averted, we sought to determine if a calibrated and measured response plan based on characteristics of the virus in the outbreak could be better defined.

To determine the cost incurred per day over the period where hospitals were at DORSCON Yellow and Orange, we obtained actual direct and indirect costs from the Operations and Finance Departments of the hospitals. Excess costs were measured by comparing these with operating costs and results over the same period in 2008.

To simulate a hospital outbreak, we used a decision analysis model to perform cost-effectiveness analysis to determine the impact of an outbreak from a single index case that was not detected by hospital surveillance and was found in the general ward. The Markov decision model was built using Treeage software (www.treeage.com), and simulation was performed based on hospital staff and inpatients (n = 7,500) over a time horizon of 30 days. Each person would transit between exclusive Markov states of Susceptible, Exposed, Incubation, Infectious, Isolated, Atypical, Recovered, or Dead. (Figure 1). The scenario assumes that all clinical cases will be identified and isolated. Infection is thus transmitted in the preclinical infectious phase or by atypical or subclinical cases not recognized and hence not isolated, as well as through the failure of personal protective equipment. Variables studied in the model included the number of persons exposed per infected patient, secondary attack rate, percentage of atypical and subclinical cases, duration of preclinical infectious period, and infectious period, as well as case-fatality rate.

Based on preliminary data available at the time of writing, comparisons were made between 3 respiratory viruses: a SARS-like virus, a 1918 Spanish influenza–like virus, and a pandemic (H1N1) 2009–type virus. Validation of the model was performed by comparing generated reproduction numbers to reported estimates from actual SARS data in Singapore (10) and Spanish influenza (for confined areas) (11) and showed consistent case and death numbers. We compared 4 different strategies: 1) no additional measures; 2) Green Alert response, which mandated personal protective equipment (PPE) for HCWs in direct contact with patients suspected of having avian influenza or other emerging infectious diseases; 3) Yellow Alert response, which mandated enhanced PPE at all high-risk areas; and 4) Orange Alert response, which mandated N95 masks for all patient contact and the restrictions described above (Table 1). Outcome measures were number of patients infected, number of deaths, cost (in US$) per case prevented, and cost per death prevented compared to baseline where no preventive measures were implemented, as well as incremental cost per death averted compared with the corresponding lower level of alert status. Multivariate sensitivity analysis was performed to understand the impact of viral characteristics as well as different hospital response policies on cost-effectiveness outcomes. The number of persons exposed in hospital and protective gear failure rates were from an actual outbreak simulation exercise performed at our hospital (12). Because there were no cases of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus infections during this period, estimates were all based on those in the literature (13). Details of the input variables are included in Table 2.

An outbreak of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 from introduction by an HCW, a patient with undiagnosed infection, or a visitor in our hospital at base case with no protection measures will result in 2,580 infected patients at 30 days. This finding would be similar to that of seasonal influenza and correspond to a 30% attack rate. With a 0.4% mortality rate, there would be 10 deaths from infection with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus. In contrast, Spanish influenza would result in 3,210 infected patients and 161 deaths (case-fatality rate 5%). The increased number of infections in the Spanish influenza model is driven by the short incubation time of the epidemic and results in more rounds of infection rather than an increase in basic reproductive number (average number of secondary cases per index case) (14). On the other hand, because SARS has a longer incubation period and lower transmissibility rate, the number of infected patients is lower at 825 but, owing to the high case-fatality rates, 82 deaths may ensue (Table 3).

Green Alert status mandates PPE for HCWs in direct contact with patients suspected of having the infection. Transmission will thus be only through preclinical cases before they are identified and patients can be isolated or through atypical or subclinical cases that are missed. We assumed pandemic (H1N1) 2009 has a lowered 50% transmissibility for atypical or subclinical cases (15); this rate effectively reduced the infected patients to 316 with only 1 death (Figure 2, panel B). This resulted in additional costs of $95 to prevent 1 additional infected patient and $23,600 to prevent 1 death. Moving to Yellow Alert would reduce infected patients to 59 and avert all deaths. The costs to prevent additional infection and death are $3,221 and $828,000, respectively. Activating Orange alert with full PPE gear, restricting visitors, and cancelling elective procedures would halve the infections to only 24 cases with no deaths. However, the additional cost over Yellow Alert would escalate to $7,153 per infection prevented and a staggering $2.5 million to infinity for 1 death averted (Figure 3).

Simulation for Spanish influenza showed a decreased number of deaths from 31 at Green Alert to 6 at Yellow Alert and 3 at Orange Alert (Figure 2, panel B). This finding translated to $50,000 per death averted moving from Green to Yellow and $153,000 per death averted moving from Yellow Alert to Orange. For SARS, on the other hand, the incremental cost of moving from Green Alert to Yellow is $120,000 per death averted; this drops to $75,000 when moving from Yellow to Orange. This finding is mainly due to the high (10%) case-fatality rate and the relatively higher percentage of atypical patients who are missed and not isolated, a lesson learned from the actual SARS experience (Figure 3).

Sensitivity analysis showed that the factors that impacted the cost-effectiveness ratio most are case-fatality rate, patient exposure rate, and secondary attack rate (Figure 4). In the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 scenario, the case fatality-rate ranging from 0.1% (seasonal influenza) to 10% (SARS) results in the cost per death averted moving from infinity (no death) to $35,000 per death averted (Orange Alert). Similarly, changing the exposure rate from 1.5 persons/day (10% PPE failure rate, Orange Alert) to 30 persons/day (0% reduction) per infected patient changed the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio from $2.5 million per death averted to $23,000. If pandemic (H1N1) 2009 had a higher 50% transmission rate, Orange Alert would become the most cost-effective strategy. The other variables had an impact on cost per case prevented but did not impact the incremental cost per death averted ratio.

To determine the impact of hospital size on our model, we modeled our simulation on the nation’s other tertiary hospital with 1,500 beds using their actual cost records. The model estimates that 10 expected deaths in the outbreak would be reduced to 1 death under Green Alert and none in Yellow and Orange Alerts. The incremental cost/death averted is $32,000, $1.9 million, and $5.4 million when moving from Green to Yellow to Orange, respectively. Although the cost ranking is consistent with that predicted by base-case simulation, the actual incremental cost index is much higher, reflecting the higher cost for activating alert status in a bigger hospital.

Singapore and many of the other countries badly affected by the SARS epidemic of 2003 launched comprehensive pandemic response plans based on a SARS model (5). The lessons of the SARS epidemic, in particular the effect of protecting HCWs from patients with undiagnosed, unisolated respiratory viral infections (16,17), have been applied rigorously to the pandemic plans of the Singapore Ministry of Health. Although it is difficult to quantify the impact of these interventions when they are taken as a whole, data from our modeling show that a nuanced approach that concentrates on administrative measures to isolate patients and selectively use PPE when working with patients suspected of having novel strains of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus would have a relatively favorable cost-effectiveness ratio.

On the other hand, the psychological and economic impact of SARS has been described as one of Singapore’s most traumatic experiences and one that left deep scars on the healthcare system of this country (18). It could be and has been argued that a draconian approach that seeks to protect all HCWs fully ensures that every case of influenza is identified early and contacts traced. Any healthcare facility ensuring no second- or third-generation transmission would provide intangible gains that exceed the economic costs of such a strategy. Nevertheless, this desire must still be balanced against the community impact of a disease such as influenza, which has a different epidemiology than SARS (7). We currently believe that pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus causes predominantly community-based disease (13). Data from the United States, where infection control recommendations (19) are similar to our DORSCON Green, have not shown any evidence to date of large nosocomial outbreaks.

In our model, we have shown that cost-effectiveness ratio is dependent on the interplay between exposure rate, transmissibility (secondary attack rate), case-fatality rate, and risk of transmission from atypical cases. Infectious diseases with high fatality rates and transmission from atypical cases (such as SARS) will need the full benefit of PPE to reduce mortality rates. This finding is reflected in Orange Alert having a better cost-effectiveness ratio than Yellow Alert. Mild diseases with low fatality rates, such as pandemic (H1N1) 2009, and low incidence of atypical or subclinical infectious cases have the best cost-effectiveness ratio at Green Alert provided surveillance measures are able to identify infected patients and isolate them early. The cost-effectiveness ratio increases exponentially after that due to the much higher costs incurred. However, although Yellow Alert comes at a heavier price tag, it effectively averts any deaths. Activating Orange Alert increases cost with minimal benefit in mortality rate reduction. In reality, our model suggests that parallel efforts in contact tracing and voluntary quarantine may further reduce the exposure rate and break the chain of transmission.

Our base model took into account only direct costs associated with each alert status. In real situations, indirect costs such as lost revenues from cancellation of elective surgeries to free up hospital resources, decreased elective admissions and outpatient attendances, administrative costs associated with senior staff meetings, and lost clinical teaching time, add up to more than the direct costs and would magnify the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio further. In fact, if direct and indirect costs were included in the modeling, the incremental cost/death averted ratio of moving from Yellow Alert to Orange in pandemic (H1N1) 2009 increased to a staggering $8–$81 million for both hospitals. Although these indirect costs are not part of the infection control process per se, surge capacity response plans to ensure that the healthcare system has the reserve capacity to react to a full-blown community outbreak are critical to all pandemic plans (20) and contribute serious costs to the hospital.

The major limitations of our study are that we have simulated a situation in which community infection is still relatively low and the outbreak in hospital arises from 1 index case. When a community epidemic is established, the incidence of new index cases entering the institution increases, especially if there are prevalent atypical or subclinically infected persons. In such a scenario the cost-effectiveness ratio of higher alert status will decrease, and it may become more beneficial to escalate protective measures.

Cost-effectiveness analyses merely provide a mathematical projection to better understand the key factors that affect outcomes. The actual magnitude of the cost-effectiveness will vary depending on institutional cost, which varies between different sized hospitals and whether direct or indirect costs are included. Nonetheless, knowledge of the exponential relationship of the different viruses on the cost-effectiveness ranking is critical in charting response policy. Indirect costs of an uncontrolled pandemic are also economic and social, especially in Singapore where the economy is dependent on trade and tourism. A higher cost-effectiveness ratio does not imply that additional lives are not worth saving. In the case of pandemic (H1N1) 2009, if it costs $2.5 million to prevent 1 death, using a median age of 37 years for persons who died (21) and expected life expectancy of 80 years (22), the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio works out to $40,000 per life-year saved. In addition, preventive measures go beyond saving lives and include resultant savings from reducing hospitalization of infected patients and prolonged intensive care with mechanical ventilation for severe cases, as well as the logistic costs of further contact tracing and quarantine.

We have not factored the cost of influenza antiviral prophylaxis or the costs and effectiveness of novel vaccinations that may be required, nor did we include the costs of work-days lost from staff taking medical leave due to their being infected or being placed in quarantine. The impact of lax border controls, subclinical patients carrying the virus into the community, and closure of community institutions or even hospitals due to an outbreak were also not computed. We assumed that the hospital is a closed community with a fixed number of staff and patients. This obviously is not true in real life but is mitigated in our analysis because the same assumption is applied to every response measure and the outcomes are incremental indices over another level of protection.

From the perspective of a healthcare institution, how do we predict the virulence of new virus early in the outbreak and adopt the most cost-effective response policy? If a mild epidemic spreads rapidly through the community, there might be multiple points of entry into the hospital; however, such a mild community outbreak might present more commonly to primary healthcare clinics and presentations to hospital may be few. Thus a step-up approach from Green to Yellow in accordance with predicted risks as we have shown may be the most cost-effective approach.

It is not known for certain how pandemic (H1N1) 2009 will behave in subsequent waves. Although the new virus seems to have relatively low virulence, the virus might reemerge with a case-fatality rate more like that of the 1918 influenza pandemic or the SARS pandemic. Our model shows that DORSCON Green, which focuses on infection control for suspected cases, will achieve a relatively high degree of protection for our staff, patients, and visitors even in the setting of a higher case-fatality rate. The main advantage of DORSCON Yellow and Orange is that undetected infected persons that are not isolated are less likely to become a source of transmission if there is universal use of N95 masks. This has to be balanced with the degree of compliance that can be achieved by the use of full-scale PPE for patients with no risk of the disease (e.g., patients with trauma or other medical or surgical conditions) and the well known adverse effects of prolonged use of N95 masks (23).

However, it is useful to also note that although a step-up approach may be the most cost-effective for the healthcare institution, the appropriate policy stance at the national level may not necessarily be the same. Our model did not take into account the psychological and economic impact to the country and the larger healthcare system, which are serious factors to consider when making a policy decision on the appropriate response across the healthcare system. Singapore, Hong Kong, and China were among the settings most severely affected by the SARS outbreak in 2003. In the initial face of an unknown virus with a perceived high mortality rate in Mexico, Singapore’s response to first err on the side of safety and make adjustments dynamically as the situation became clearer therefore would be reasonable when viewed from the larger perspective.

Such actions, however, were not without their own adverse effects in terms of cost and in overall patient care at the healthcare institution. We had the opportunity to perform a cost-effectiveness analysis using the actual costs incurred from this heightened infection control response. We have quantified how the virulence or case-fatality rate of a respiratory viral infection has a serious impact on the hospital infection control response. This impact occurs at 2 levels, first, the actual number of deaths and ill persons, and second, the direct and indirect costs on the hospital in terms of activation, logistics, and lost revenue. This impact is reflected in the subsequent responses of Singapore and other countries when the virulence of the novel influenza virus appeared to be much less than previously feared. Understanding the key factors that affect the cost-effectiveness ratio will enable us to make better informed decisions as we prepare to respond to future epidemics.

Dr Dan is assistant professor at the Department of Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, National University Health System. His research interests are healthcare modeling and cost-effectiveness analysis.

Acknowledgment

We thank the National University Health System Medical Publications Support Unit, Singapore, for assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- World Health Organization. Epidemic and pandemic alert and response (EPR) [cited 2009 Aug 29]. Available from http://www.who.int/csr/don/2009_08_28/en/index.html

- Hsu LY, Lee CC, Green JA, Ang B, Paton NI, Lee L, Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Singapore: clinical features of index patient and initial contacts. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:713–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tambyah PA. Severe acute respiratory syndrome from the trenches, at a Singapore university hospital. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:690–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Leong HN, Chan KP, Oon LL, Koay ES, Ng LC, Lee MA, Clinical and laboratory findings of SARS in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35:332–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Singapore Ministry of Health. Influenza pandemic plan [cited 2009 May 22]. Available from http://www.moh.gov.sg/mohcorp/uploadedFiles/News/Current_Issues/2007/Main%20Document%20Public%20_Jan09.pdf

- Blumenfeld HL, Kilbourne ED, Louria DB, Rogers DE. Studies on influenza in the pandemic of 1957–1958. I. An epidemiologic, clinical and serologic investigation of an intrahospital epidemic, with a note on vaccination efficacy. J Clin Invest. 1959;38:199–212. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Serwint J. Pediatrician-dependent barriers in influenza vaccine administration. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12:956–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Voirin N, Barret B, Metzger MH, Vanhems P. Hospital-acquired influenza: a synthesis using the Outbreak Reports and Intervention Studies of Nosocomial Infection (ORION) statement. J Hosp Infect. 2009;71:1–14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Salgado CD, Farr BM, Hall KK, Hayden FG. Influenza in the acute hospital setting. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:145–55. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lipsitch M, Cohen T, Cooper B, Robins JM, Ma S, James L, Transmission dynamics and control of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1966–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vynnycky E, Trindall A, Mangtani P. Estimates of the reproduction numbers of Spanish influenza using morbidity data. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:881–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Seet RC, Lim EC, Oh VM, Ong BK, Goh KT, Fisher DA, Readiness exercise to combat avian influenza. QJM. 2009;102:133–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team; Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, Shaw MW, Lindstrom S, Garten RJ, et al. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2605–15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mills CE, Robins JM, Lipsitch M. Transmissibility of 1918 pandemic influenza. Nature. 2004;432:904–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stilianakis NI, Perelson AS, Hayden FG. Emergence of drug resistance during an influenza epidemic: insights from a mathematical model. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:863–73.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tan CC. SARS in Singapore—key lessons from an epidemic. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35:345–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tan TT, Tan BH, Kurup A, Oon LL, Heng D, Thoe SY, Atypical SARS and Escherichia coli bacteremia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:349–52.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sim K, Chua HC. The psychological impact of SARS: a matter of heart and mind. CMAJ. 2004;170:811–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. Interim guidance for infection control for care of patients with confirmed or suspected novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in a healthcare setting [cited 2009 May 25]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/guidelines_infection_control.htm

- Schull MJ, Stukel TA, Vermeulen MJ, Guttmann A, Zwarenstein M. Surge capacity associated with restrictions on nonurgent hospital utilization and expected admissions during an influenza pandemic: lessons from the Toronto severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1228–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vaillant L, La Ruche G, Taratola A, Barboza P. Epidemic Intelligence Team at InVS. Epidemiology of fatal cases associated with pandemic H1N1 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:1–3.

- Singapore Department of Statistics. Key annual indicators [cited 2009 Aug 28]. Available from http://www.singstat.gov.sg/stats/keyind.html

- Lim EC, Seet RC, Lee KH, Wilder-Smith EP, Chuah BY, Ong BK. Headaches and the N95 face-mask amongst healthcare providers. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;113:199–202. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 15, Number 12—December 2009

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Paul A. Tambyah, Department of Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, National University Health System, 5 Lower Kent Ridge Rd, NUH Level 3, Singapore 119074

Top