Volume 15, Number 3—March 2009

Dispatch

Evaluation of Commercially Available Anti–Dengue Virus Immunoglobulin M Tests

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

Anti–dengue virus immunoglobulin M kits were evaluated. Test sensitivities were 21%–99% and specificities were 77%–98% compared with reference ELISAs. False-positive results were found for patients with malaria or past dengue infections. Three ELISAs showing strong agreement with reference ELISAs will be included in the World Health Organization Bulk Procurement Scheme.

An estimated 2.5–3 billion persons live in tropical and subtropical regions where dengue virus (DENV) is transmitted (1–3). Absence of inexpensive and accurate tests to diagnose dengue makes case management, surveillance, and outbreak investigation difficult. During infection, immunoglobulin (Ig) M against DENV can often be detected ≈5 days after onset of fever (4–6). First-time (primary) DENV infections typically have a stronger and more specific IgM response than subsequent (secondary) infections, for which the IgM response is low compared with a strong IgG response. These patterns underscore the need for evaluating the performance of commercially available tests, especially for diagnosis of secondary DENV infections (7–10).

To provide independent evaluation of dengue diagnostic tests, the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund/United Nations Development Programme/World Bank/World Health Organization Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases and the Pediatric Dengue Vaccine Initiative established a network of 7 laboratories based on criteria related to dengue expertise of the principal investigator, and type, capacity, management of the laboratory. The laboratories contributed serum specimens for the evaluation panel and conducted the evaluation. The 7 laboratories were located at Mahidol University (Bangkok, Thailand), Cho Quan Hospital (Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam), Institut Pasteur (Phnom Penh, Cambodia), University of Malaya (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (San Juan, PR, USA), Instituto Medicina Tropical Pedro Kouri (Havana, Cuba), and Instituto Nacional Enfermedades Virales Humanas Dr. Julio I. Maiztegui (Buenos Aires, Argentina). Laboratories at Mahidol University and CDC acted as reference laboratories by providing samples for proficiency testing among laboratories and for assembling and validating the evaluation panel.

The evaluation panel consisted of 350 well-characterized serum specimens (Table 1). Specimens positive for IgM against DENV were obtained from patients with primary and secondary infections and represented all 4 DENV serotypes. IgM levels were determined by reference standard ELISAs developed by CDC and the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Science (Bangkok, Thailand) (6,7). Positive samples were selected based on optical density (OD) and were weighted toward low and medium ODs. Negative control samples included serum samples from healthy persons in areas where dengue is not endemic and from patients with other flavivirus infections, febrile illness of other causes, or systemic conditions. Results were confirmed as negative for IgM antibodies against DENV by using predetermined reference standards. Additionally, 20 anti-DENV IgM-negative specimens were obtained from SeraCare Diagnostics (Milford, MA, USA). Panel specimens were coded, heat-inactivated, aliquoted, and lyophilized; 1 aliquot was retested by the reference laboratories after reconstitution.

Letters of interest and the evaluation protocol were sent to 20 dengue kit manufacturers. Six companies agreed to participate and provided 4 rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and 5 microplate ELISAs. Test characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Price per test ranged from US $3 to $15.

Laboratories evaluated the kits for sensitivity and specificity by using the evaluation panel. For each test, kappa coefficient values were determined to assess agreement of mean sensitivity and specificity of each test with the reference standard. A test of homogeneity was used to determine extent of agreement of results among sites.

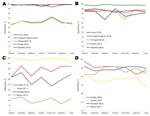

Mean sensitivities of ELISAs were 61.5%–99.0%, and specificities were 79.9%–97.8% (Figure 1, panels A and B). Tests from Panbio Diagnostics (Windsor, Queensland, Australia), Focus Diagnostics (Cypress, CA, USA), and Standard Diagnostics (Kyonggi-do, South Korea) showed significantly higher mean sensitivities (99.0%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 98.4%–99.5%; 98.6%, 95% CI 98.0%–99.2%; and 97.6%, 95% CI 96.8%–98.4%, respectively) than 2 tests from Omega Diagnostics (Alva, UK) (62.3% and 61.5%; p<0.0001 for all comparisons). The Omega Pathozyme Capture test showed significantly higher mean specificity (97.8%, 95% CI 97.0%–98.6%) than the other ELISAs (79.9%–86.6%; p≤0.02 for all comparisons). The Focus, Panbio, and Standard ELISAs showed strong agreement with the reference standard (kappa values 0.81–0.85). Kappa values for Omega kits were below the acceptable range (0.46 and 0.59). Site-to-site variation for ELISAs was not significant (homogeneity >0.05).

Mean sensitivities of RDTs were 20.5%–97.7%, and specificities were 76.6%–90.6% (Figure 1, panels C and D). None had an acceptable kappa value for overall performance compared with reference methods. The Pentax (Tokyo, Japan) test had significantly higher mean sensitivity (97.7%, 95% CI 96.9%–98.5%) than all other RDTs (p<0.0001 for all comparisons), but lowest mean specificity (76.6%, 95% CI 74.1%–79.0%; p<0.0001 for all comparisons) and high false-positive rates for malaria and anti-DENV IgG specimens (Figure 2). Panbio and Standard tests showed high mean specificities (90.6%, 95% CI 88.9%–92.3%, and 90.0%, 95% CI 88%.3–91.7%) with different mean sensitivities (77.8%, 95% CI 75.5%–80.1%, and 60.9%, 95% CI 58.2%–63.6%).

This laboratory-based evaluation used a serum panel to determine the ability of 9 commercially available anti-DENV IgM tests to detect low levels of IgM and to determine specificity against pathogens that often cocirculate with DENV. Field trials are needed to determine the performance and utility of these tests in a local context.

Of the 5 ELISA kits evaluated, 3 (Focus, Panbio, and Standard) showed strong agreement with reference standard results and were consistent across all evaluation sites. Of concern are false-positive results shown by some tests on sera that were anti-DENV IgM negative but malaria positive, anti-DENV IgG positive, or rheumatoid factor positive. The laboratory at Mahidol University also tested the kits against 12 serum samples from patients with leptospirosis. The Panbio ELISA showed cross-reactivity with 58% of these samples, and the Focus ELISA showed cross-reactivity with 25%. Further studies are needed to elucidate the cause of this cross-reactivity.

Technicians were asked to score tests’ user-friendliness. All RDTs scored higher than ELISAs, and the Panbio RDT scored highest.

Limitations of anti-DENV IgM tests include their inability to identify the infecting DENV type and potential antibody cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses (11,12). However, cross-reactivity to related viruses did not appear to be a problem with these tests. IgM tests can be useful for surveillance and support diagnosis of DENV infection in conjunction with clinical symptoms, medical history, and other epidemiologic information (13). Because IgM persists for >60 days, IgM assays should not be used in dengue-endemic countries as confirmatory tests for current illness. Presence of IgM indicates that a dengue infection has occurred in the past 2–3 months.

This evaluation has several limitations. Test performance was compared with reference laboratory assay results, which may be less sensitive than commercial assays, leading to some results being misclassified as false positive. Specificity of these tests may be higher in a field setting than in this evaluation because not all potential causes of false-positive results would be present. The panel consisted of a high proportion of specimens from persons with secondary DENV infections. Thus, the panel was weighted toward lower anti-DENV IgM levels. However, this feature reflects the situation in most dengue-endemic countries. Thus, tests that performed well against this panel could be expected to perform well in these diagnostic settings. We could not comprehensively evaluate whether the kits could detect primary infections with all 4 DENVs because all DENV types were not represented in the panel.

Data from this evaluation have been provided to the manufacturers and WHO member states. On the basis of these results, ELISAs from Focus, Panbio, and Standard Diagnostics will be included in the WHO Bulk Procurement Scheme. Technical discussions are ongoing to determine how tests might be improved to accelerate availability of useful methods for dengue case management, surveillance, and disease control.

Dr Hunsperger is a virologist and chief of the Serology Diagnostics and Viral Pathogenesis Research Section at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Her primary research interest is the pathogenesis of dengue virus and West Nile virus.

Acknowledgments

We thank Naifi Calzada, Ew Cheng Lan, Maria Alejandra Morales, Didye Ruiz, Ong Sivuth, and Duong Veasna for technical assistance; and Jane Cardosa for helpful comments in preparing this article.

This study was supported by the Pediatric Dengue Vaccine Initiative and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund/United Nations Development Programme/World Bank/World Health Organization Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases.

References

- World Health Organization 2008. Dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. Factsheet no. 117, revised May 2008 [cited 2008 Jun 5]. Available from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en

- Gubler D. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever: its history and resurgence as a global public health problem. In: Gubler DJ, Kuno G, editors. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Cambridge (MA): CAB International; 1997. p. 1–22.

- Guzman MG, Kouri G. Dengue diagnosis, advances and challenges. Int J Infect Dis. 2004;8:69–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vaughn DW, Green S, Kalayanarooj S, Innis BL, Nimmannitya S, Suntayakorn S, Dengue in the early febrile phase: viremia and antibody responses. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:322–30.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Innis BL, Nisalak A, Nimmannitya S, Kusalerdchariya S, Chongswasdi V, Suntayakorn S, An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to characterize dengue infections where dengue and Japanese encephalitis co-circulate. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:418–27.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Burke DS, Nisalak AA, Ussery MM. Antibody capture immunoassay detection of Japanese encephalitis virus immunoglobulin M and G antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16:1034–42.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Miagostovich MP, Nogueira RM, dos Santos FB, Schatzmayr HG, Araujo ES, Vorndam V. Evaluation of an IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for dengue diagnosis. J Clin Virol. 1999;14:183–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Groen J, Koraka P, Velzing J, Copra C, Osterhaus AD. Evaluation of six immunoassays for detection of dengue virus–specific immunoglobulin M and G antibodies. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:867–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kit Lam S, Lan Ew C, Mitchell JL, Cuzzubo AJ, Devine PL. Evaluation of capture screening enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for combined determination of immunoglobulin M and G antibodies. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:850–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Blacksell SD, Newton PN, Bell D, Kelley J, Mammen MP, Vaughn DW, The comparative accuracy of 8 rapid immunochromatographic assays for the diagnosis of acute dengue virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1127–34. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vázquez S, Valdés O, Pupo M, Delgado I, Alvarez M, Pelegrino JL, MAC-ELISA and ELISA inhibition methods for detection of antibodies after yellow fever vaccination. J Virol Methods. 2003;110:179–84. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wichmann O, Gascon J, Schunk M, Puente S, Siikamaki H, Gjørup I, European Network on Surveillance of Imported Infectious Diseases. Severe dengue virus infection in travelers: risk factors and laboratory indicators. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1089–96. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 15, Number 3—March 2009

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Rosanna W. Peeling, Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, World Health Organization, 20 Ave Appia, Geneva, Switzerland;

Top