Volume 16, Number 7—July 2010

Dispatch

Cryptococcus gattii Genotype VGIIa Infection in Man, Japan, 2007

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

We report a patient in Japan infected with Cryptococcus gattii genotype VGIIa who had no recent history of travel to disease-endemic areas. This strain was identical to the Vancouver Island outbreak strain R265. Our results suggest that this virulent strain has spread to regions outside North America.

Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii are closely related species of yeast; C. gattii was previously classified as C. neoformans var. gattii (1). Although both species cause pulmonary or central nervous system infections, they differ in their ecology, epidemiology, and pathobiology. C. neoformans is the most common Cryptococcus spp. worldwide and mainly affects immunocompromised hosts. In contrast, C. gattii mainly affects immunocompetent hosts and often forms mass-like lesions (cryptococcomas).

Multilocus sequence typing can be used to divide this species into 4 molecular genotypes, VGI–VGIV, which differ in epidemiology and virulence (1,2). C. gattii was believed to be restricted to tropical and subtropical areas such as Australia, Southeast Asia, and South America (1). However, in 1999, a C. gattii infection outbreak occurred on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada (3), which has a temperate climate.

During the Vancouver Island outbreak, most human, animal, and environmental isolates obtained belonged to VGIIa (major genotype, 90%–95% of isolates) and VGIIb (minor genotype, 5%–10% of isolates) (2,3). These strains have now spread to mainland British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest region of the United States (1,4,5). The potential for further spread of this strain, particularly the VGIIa genotype, is a serious concern because it is highly virulent in mammals and can infect immunocompetent persons (2).

We report a case of cerebral cryptococcoma caused by C. gattii VGIIa (a strain identical to the Vancouver Island outbreak major genotype strain R265) in a patient from Japan who had no recent travel history to known disease-endemic areas.

In 2007, a 44-year-old man (sign painter) from Japan who was not infected with HIV came to the University of Tokyo Hospital with a 2-month history of headache and loss of right-sided vision in both eyes (right homonymous hemianopsia). He had had a diagnosis of hyperglycemia 3 years before admission but had declined to seek medical treatment. His medical history was otherwise unremarkable. He was an ex-smoker who rarely consumed alcohol and was not taking any prescription medications (including corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive drugs). He had traveled to Guam in 1990 and Saipan in 1999 and had no other history of overseas travel. He reported exposure to his dog, and he did not spend time in wilderness areas. The patient often worked near construction sites in urban locations.

When hospitalized, the patient was afebrile and had stable vital signs. Physical examination showed agraphia (inability to write), anarithmia (inability to count numbers), right homonymous hemianopsia, and Romberg sign. Laboratory evaluations showed increased glucose (367 mg/dL) and hemoglobin A1c (10.5%) levels. Results of a complete blood cell count and hepatic and renal function tests were within normal limits. Levels of electrolytes and C-reactive protein were also within normal limits. Results of a test for antibodies to HIV-1/2 were negative.

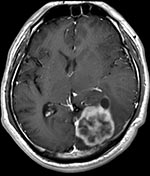

An enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging scan showed a 4.4 × 4.1 × 3.3–cm lobulated mass in the left occipital lobe with surrounding edema. The lesion had low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, moderate signal intensity on T2-weighted images, and rim enhancement on T1-weighted images after administration of gadolinium (Figure). A chest computed tomography scan showed a 1.8 × 1.2–cm nodule in the left lower lung (S8 segment).

The brain mass was completely resected because it was suspected to be a tumor. Pathologic evaluation of the resected specimen showed that the mass was a large abscess containing encapsulated yeast. The yeast could be seen after staining with periodic acid–Schiff and Grocott methenamine silver stains. Specimen cultures were positive for Cryptococcus spp. and led to a diagnosis of cerebral cryptococcosis.

The patient was treated with liposomal amphotericin B (4 mg/kg/d for 3 weeks) and flucytosine (100 mg/kg/d for 3 weeks). A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample obtained by lumbar puncture soon after mass resection showed a slightly increased protein level but no leukocytosis or a low glucose concentration. Fungal cultures of the CSF showed negative results. Cryptococcal antigen titers were >512 in serum and 64 in CSF.

After 3 weeks of induction therapy, the patient received consolidation and maintenance therapy (oral fluconazole, 400 mg/d) for 1 year. The pulmonary nodule decreased in size after antifungal treatment, suggesting that this lesion was a pulmonary cryptococcoma. At the 1-year follow-up visit, the cerebral cryptococcoma had not recurred, and the pulmonary nodule had disappeared.

The cryptococcal strain isolated from the brain was identified as serotype B by slide agglutination test (6) and identified as C. gattii by rRNA gene sequence analysis (7). Eleven unlinked loci (SXI1, IGS, TEF1, GPD1, LAC1, CAP10, PLB1, MPD1, HOG1, BWC1, and TOR1) analyzed by multilocus sequence typing, according to the method of Fraser et al. (2), were identical to those of the Vancouver Island major genotype strain R265 (genotype VGIIa) (Table) (2,8,9). MICs of this isolate were 0.125, 0.5, 1.0, and 0.011 µg/mL for amphotericin B, flucytosine, fluconazole, and itraconazole, respectively.

Japan has not been considered a C. gattii–endemic area. There have been only 2 reports of C. gattii infections in Japan; both infections apparently originated in Australia (10,11). Retrospective surveillance studies found no evidence of C. gattii infection or colonization in Japan (12; Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan, 2003, unpub. data). Although the source of the infection in the patient reported here has not been identified, it appears to have originated in Japan. Infections with C. gattii have not been reported in the places the patient had visited (Guam and Saipan) (13,14). Analysis of persons who traveled to Vancouver Island indicated that the median incubation period of C. gattii infection is 6–7 months (range 2–11 months) (13), although an incubation period of 13 months has been reported for 1 patient (14).

C. gattii genotype VGIIa may have been present in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States long before the Vancouver Island outbreak (2,4). However, no human cases were identified in the United States until January 2006 (4,5). Genotype VGIIa has now spread from Vancouver Island to mainland British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest region of the United States, possibly because of human activity or animal migration (1). However, this genotype has not been reported in any other region, although similar isolates have been obtained from South America (1) and from patients who had traveled to affected areas (1,8). Thus, our findings indicate possible global dispersal of this strain.

Our results suggest that C. gattii VGIIa genotype may be spreading. In North America, this genotype has been isolated from various environmental specimens such as tree surfaces, soil, water, and air (1,4). Soil is believed to be a major potential reservoir of this organism (1,15). Thus, ecologic and environmental studies on C. gattii in Japan are needed to determine likely reservoirs and to improve understanding of C. gattii epidemiology. Although many clinical laboratories in Japan currently do not differentiate between C. neoformans and C. gattii infections, identification of cryptococcal isolates to the species level, especially in apparently immunocompetent patients, is needed.

Dr Okamoto is a chief resident in the Department of Infectious Diseases at the University of Tokyo Hospital. His research interests are infections in immunocompromised patients and fungal infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katsuhiko Kamei for valuable suggestions.

This study was supported in part by a Health Science Research grant for “Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases” to T.S. from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan.

References

- Dixit A, Carroll SF, Qureshi ST. Cryptococcus gattii: an emerging cause of fungal disease in North America. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2009;2009:840452.

- Fraser JA, Giles SS, Wenink EC, Geunes-Boyer SG, Wright JR, Diezmann S, Same-sex mating and the origin of the Vancouver Island Cryptococcus gattii outbreak. Nature. 2005;437:1360–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kidd SE, Hagen F, Tscharke RL, Huynh M, Bartlett KH, Fyfe M, A rare genotype of Cryptococcus gattii caused the cryptococcosis outbreak on Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17258–63. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Datta K, Bartlett KH, Baer R, Byrnes E, Galanis E, Heitman J, Spread of Cryptococcus gattii into Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1185–91. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Upton A, Fraser JA, Kidd SE, Bretz C, Bartlett KH, Heitman J, First contemporary case of human infection with Cryptococcus gattii in Puget Sound: evidence for spread of the Vancouver Island outbreak. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3086–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ikeda R, Shinoda T, Fukazawa Y, Kaufman L. Antigenic characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans serotypes and its application to serotyping of clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16:22–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sugita T, Ikeda R, Shinoda T. Diversity among strains of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii as revealed by a sequence analysis of multiple genes and a chemotype analysis of capsular polysaccharide. Microbiol Immunol. 2001;45:757–68.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Byrnes EJ III, Li W, Lewit Y, Perfect JR, Carter DA, Cox GM, First reported case of Cryptococcus gattii in the southeastern USA: implications for travel-associated acquisition of an emerging pathogen. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5851. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Byrnes EJ III, Bildfell RJ, Frank SA, Mitchell TG, Marr KA, Heitman J. Molecular evidence that the range of the Vancouver Island outbreak of Cryptococcus gattii infection has expanded into the Pacific Northwest in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:1081–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tsunemi T, Kamata T, Fumimura Y, Watanabe M, Yamawaki M, Saito Y, Immunohistochemical diagnosis of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii infection in chronic meningoencephalitis: the first case in Japan. Intern Med. 2001;40:1241–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Makimura K, Karasawa M, Hosoi H, Kobayashi T, Kamijo N, Kobayashi K, A Queensland koala kept in a Japanese zoological park was carrier of an imported fungal pathogen, Filobasidiella neoformans var. bacillispora (Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii). Jpn J Infect Dis. 2002;55:31–2.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kohno S, Varma A, Kwon-Chung KJ, Hara K. Epidemiology studies of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans of Japan by restriction fragment length polymorphism. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1994;68:1512–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- MacDougall L, Fyfe M. Emergence of Cryptococcus gattii in a novel environment provides clues to its incubation period. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1851–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Georgi A, Schneemann M, Tintelnot K, Calligaris-Maibach RC, Meyer S, Weber R, Cryptococcus gattii meningoencephalitis in an immunocompetent person 13 months after exposure. Infection. 2009;37:370–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kidd SE, Chow Y, Mak S, Bach PJ, Chen H, Hingston AO, Characterization of environmental sources of the human and animal pathogen Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia, Canada, and the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1433–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Table

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 16, Number 7—July 2010

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Shuji Hatakeyama, Department of Infectious Diseases, University of Tokyo Hospital, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8655, Japan

Top