Volume 17, Number 1—January 2011

Dispatch

Tick-borne Encephalitis Virus in Wild Rodents in Winter, Finland, 2008–2009

Figure 2

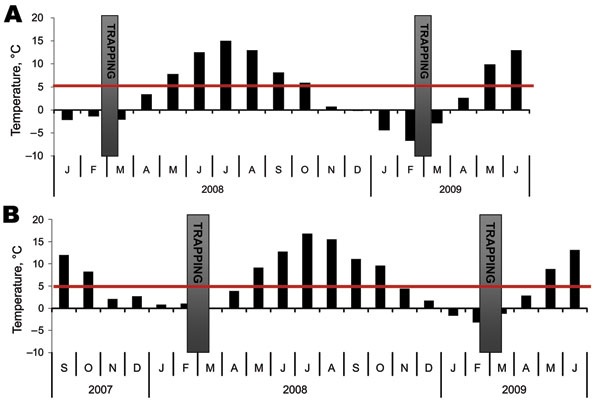

Figure 2. Monthly day and night mean temperatures at the trapping sites. Daily maximum temperatures had not reached 5°C for >50 days before trapping. Tick-feeding season is considered to begin when temperature in the ground reaches the tick activity limit and stays above it (1). A) Kokkola archipelago, where Siberian subtype of tick-borne encephalitis virus is endemic. B) Helsinki archipelago, where European subtype of tick-borne encephalitis virus is endemic. Although trapping was conducted on Isosaari, temperature data were unavailable and were instead collected on Harmaja, a nearby island (Figure 1). Gray bars indicate time of trapping; red line indicates tick activity limit. Data source: Finnish Meteorological Institute (http://ilmatieteenlaitos.fi/en/).

References

- Labuda M, Kozuch O, Zuffová E, Elecková E, Hails RS, Nuttall PA. Tick-borne encephalitis virus transmission between ticks cofeeding on specific immune natural rodent hosts. Virology. 1997;235:138–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mansfield KL, Johnson N, Phipps LP, Stephenson JR, Fooks AR, Solomon T. Tick-borne encephalitis virus—a review of an emerging zoonosis. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:1781–94. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Moshkin MP, Novikov EA, Tkachev SE, Vlasov VV. Epidemiology of a tick-borne viral infection: theoretical insights and practical implications for public health. Bioessays. 2009;31:620–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ecker M, Allison SL, Meixner T, Heinz FX. Sequence analysis and genetic classification of tick-borne encephalitis viruses from Europe and Asia. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:179–85.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Grard G, Moureau G, Charrel RN, Lemasson J-J, Gonzalez J-P, Gallian P, Genetic characterization of tick-borne flaviviruses: New insights into evolution, pathogenic determinants and taxonomy. Virology. 2007;361:80–92. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Randolph SE, Rogers DJ. Fragile trans mission cycles of tick-borne encephalitis may be disrupted by predicted climate change. Proc Biol Sci. 2000;267:1741–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Han X, Aho M, Vene S, Peltomaa M, Vaheri A, Vapalahti O. Prevalence of tick-borne encephalitis virus in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Finland. J Med Virol. 2001;64:21–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jääskeläinen AE, Tikkakoski T, Uzcátegui NY, Alekseev AN, Vaheri A, Vapalahti O. Siberian subtype tickborne encephalitis virus, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1568–71.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schwaiger M, Cassinotti P. Development of a quantitative real-time RT-PCR assay with internal control for the laboratory detection of tick borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) RNA. J Clin Virol. 2003;27:136–45. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Puchhammer-Stöckl E, Kunz C, Mandl CW, Heinz FX. Identification of tick-borne encephalitis virus ribonucleic acid in tick suspensions and in clinical specimens by a reverse transcription–nested polymerase chain reaction assay. Clin Diagn Virol. 1995;4:321–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Randolph SE. The shifting landscape of tick-borne zoonoses: tick-borne encephalitis and Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:1045–56. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bakhvalova VN, Potapova OF, Panov VV, Morozova OV. Vertical transmission of tick-borne encephalitis virus between generations of adapted reservoir small rodents. Virus Res. 2009;140:172–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bakhvalova VN, Dobrotvorsky AK, Panov VV, Matveeva VA, Tkachev SE, Morozova OV. Natural tick-borne encephalitis virus infection among wild small mammals in the southeastern part of western Siberia, Russia. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2006;6:32–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kozuch O, Labuda M, Lysý J, Weismann P, Krippel E. Longitudinal study of natural foci of central European encephalitis virus in west Slovakia. Acta Virol. 1990;34:537–44.PubMedGoogle Scholar