Volume 19, Number 12—December 2013

Research

Spontaneous Generation of Infectious Prion Disease in Transgenic Mice

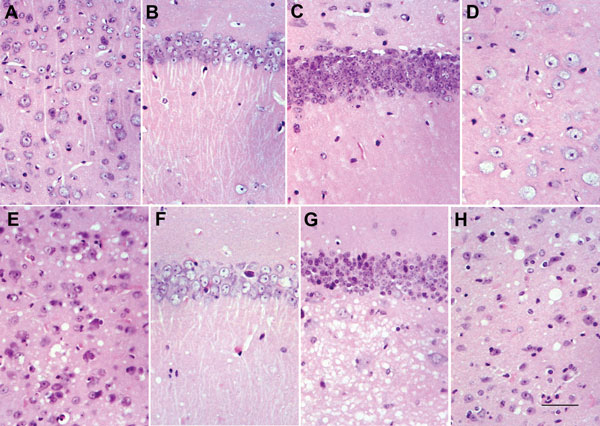

Figure 2

Figure 2. . . Comparison between homozygous bovine prion protein (BoPrP)-Tg110+/+ control mice (panels A–D) and hemizygous 113LBoPrP-Tg037+/− mice with end-stage disease (panels E–H) in parietal cortex (panels A and E), CA1 region of the hipocampus (panels B and F), dentate gyrus (panels C and G), and medial thalamus (panels D and H). Severe spongiosis is seen in the cerebral cortex, hilus ofdentate gyrus, and medial thalamus, but not in the CA1 area of the hippocampus and granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus. 113L, leucine substitution at codon 113. Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Scale bar in panel H = 25 μm.

Page created: November 19, 2013

Page updated: November 19, 2013

Page reviewed: November 19, 2013

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.