Volume 19, Number 5—May 2013

About the Cover

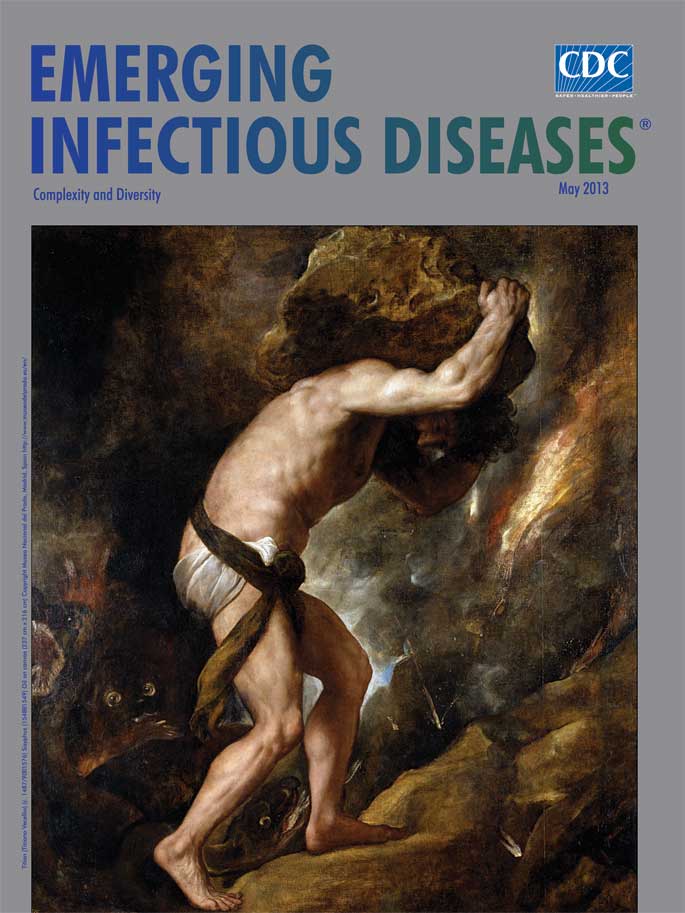

Imagining Sisyphus Happy

“And I saw Sisyphus in agonizing torment trying to roll a huge stone to the top of a hill,” wrote Homer in The Odyssey. “He would brace himself, and push it towards the summit with both hands, but just as he was about to heave it over the crest its weight overcame him, and then down again to the plain came bounding that pitiless boulder. He would wrestle again, and lever it back, while the sweat poured from his limbs, and the dust swirled round his head.” This ancient myth about “the craftiest of men,” whose irreverence so outraged the gods that they sentenced him to endless futile and hopeless labor, has long captured the imagination of poets but also philosophers and artists alike, among them Titian, who painted for posterity his own interpretation.

“Creation” or art is another way to express human experiences, wrote Albert Camus, in his Myth of Sisyphus (1942), a philosophical essay examining the meaning of life. The gods saw no worse punishment for Sisyphus’ mischief than sentencing him to toil for no reason toward nothing, a metaphor for the human condition. Life is absurd and without meaning. In this “unintelligible and limited universe,” humans have an “irrational and… wild longing for clarity.” “If the world were clear, art would not exist.” And, although art is not intended to explain or solve any of life’s problems, it is how humans, who still possess freedom, intelligence, desire to revolt, and passion for the beauty of nature, can remain conscious of their desire to live and strive for meaning and purpose. In the philosopher’s estimation, works of art are evidence of human dignity.

Titian’s finest works are mythologic narratives, which he likened to visual poetry. These paintings explored human frailties with empathy and lyricism. At the behest of Mary of Hungary (1505‒1558), he created a group of four paintings depicting the Damned in mythology: Tityos, Sisyphus, Tantalus, and Ixion—all condemned to perpetual torture for incurring the wrath of the gods. Only two, Tityos (his liver endlessly devoured by a vulture) and Sisyphus, have survived.

“Titian was born in Cadore, a small town on the River Piave, five miles from the pass through the Alps, to the Vecelli family, one of the noblest in those parts,” wrote Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the Artists. “And when, at the age of 10, he showed fine wit and a lively mind, he was sent to Venice to the home of an uncle, a respected citizen, who saw that the boy had a real propensity for the art of painting and who placed him with Giovanni Bellini, a skillful and very famous painter of those times.” Soon he showed that “he had been gifted by Nature with all those qualities of intelligence and judgment which are necessary for the art of painting.”

Venice was then the richest city in the world, where everything was traded, and no less color pigments, which were coveted by artists far and wide. The demand was so high that painting supplies were sold by specialists, the vendecolori. Part of an industry that encompassed members of the Venetian painters’ guild, these color vendors sold only to painters and artisans in related trades (dyers, glass makers, decorators, potters, book publishers). Commerce with Flanders exposed Venetian artists to Flemish art and the use of oil-based paints, soon adopted by local masters, among them Giovanni Bellini and the great Giorgione, Titian’s early influences. When his student’s work could no longer be distinguished from his own, Giorgione was so offended that “from that time on, he never wanted to be in Titian’s company or to be his friend.”

The undisputed master by 1550 of the Venetian School, which included such rivals as Tintoretto, Veronese, Bassano, and Lotto, Titian would soon surpass the artistic and cultural limits of the Renaissance, and become known as the founder of modern painting, which he dominated throughout his long life, noted particularly for his inventiveness and expert use of color. “His last works,” which Vasari described as “beautiful and stupendous,” are “executed with such large and bold brushstrokes and in such broad outlines that they cannot be seen from close up but appear perfect from a distance.” Furthermore, and to Vasari’s amazement, “the pictures not only seem alive but to have been executed with great skill concealing the labor.” Others said that in his visual poems, Titian embodied the greatness of Michelangelo, the grace of Raphael, and the true colors of nature.

This “sun amidst small stars,” not only in Italy but around the world, freed painting from drawing and established the brushstroke as expression in its own right. Titian died during the plague epidemic in Venice. One of his sons, his right-hand man Orazio, died of the plague the same year.

Titian left no letters or other keys to his inner life or artistic vision. His more than 500 paintings support his legendary dedication to the craft. Once, while working on the portrait of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, he dropped a brush, which the emperor promptly picked up. “Sire, one of your servants does not deserve this honor,” he protested. “Titian deserves to be served by Caesar,” Charles replied. Yet, this successful artist worried about money and had problems with his son, Pomponio. He spoke of “Pain and distress... sacrifices and sweat,” as he tried to set this wayward son on the path to riches. Artistic growth continued up to the time of his death, his brush becoming freer, less descriptive and more abstract. “I am finally beginning to learn how to paint.”

In Sisyphus Titian achieved rich color effects and chiaroscuro with a limited palette, staging the human presence against a tantalizing shadow-filled space, his own earthy presentation of the myth. Like his ancestral model often depicted on ancient vases, Titian’s Sisyphus is strong and vibrant, muscle-bound, determined, and sure-footed. His whole body is engaged, face strained against the load. The boulder is not pursued or pushed up the hill but carried on his shoulders, as in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a work familiar to the artist and probably his visual model.

Sisyphus [Gr. se-sophos = very wise or over wise] may have been the archetypal human competitor of the gods. The story has it that when Death came to take him, Sisyphus tricked and tied him up. As a result, for a time, no one could die, until Zeus intervened. Rebelliousness and love of life are essential human traits as are Sisyphean pursuits. No less so in public health and disease emergence, an endless cycle. Just as a region gets a solid grip on tuberculosis, populations shift, and the disease reappears. No sooner is a new coronavirus identified and described as SARS than a betacoronavirus with lethal respiratory and renal complications pops up in patients from countries in the Middle East. Lyssavirus, a known culprit, reinvents itself in Spain. Acinetobacter travels from North Africa to France. For all the reasons infectious diseases emerge, they can reemerge, morph into something new, and metastasize. And public health workers keep pushing the rock up the hill.

Despite darkness and futility in the world, Titian imagined Sisyphus thundering upward at his task. Despite the absurd, Camus surmised that “the struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill one’s heart,” concluding that one “must imagine Sisyphus happy.” And in public health, where monumental effort sometimes brings incremental improvement, success is still measured by tying up Death.

Bibliography

- Bonnin RA, Cuzon G, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clone, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:822–3. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Brown DA. Bellini, Giorgione, Titian and the Renaissance of Venetian painting. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press; 2006.

- Camus A. The myth of Sisyphus. New York: Vintage Books; 1955.

- Ceballos NA, Morón SA, Berciano JM, Nicholás O, López CA, Juste J, Novel lyssavirus in Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:793–5. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Cotten M, Lam TT, Watson SJ, Palser AL, Petrova V, Grant P, Full-genome deep sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of novel human betacoronavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:736–42. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Hale S. Titian: his life. London: Harper Press; 2012.

- Homer . The Odyssey, Book XI [cited 2013 Mar 29]. http://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Greek/Odyssey11.htm#_Toc90267986

- Langlois-Klassen D, Senthilselvan A, Chui L, Kunimoto D, Saunders LD, Menzies D, Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing strains, Alberta, Canada, 1991–2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:701–11. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Ridolfi C. The life of Titian. Bondanella JC, Bondanella P, translators. University Park (PA). The Pennsylvania State University Press; 1996.

- Vasari G. A description of the works of Titian of Cadore, painter. In the lives of the artists. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 1998.

Related Links

Table of Contents – Volume 19, Number 5—May 2013

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Polyxeni Potter, EID Journal, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Rd NE, Mailstop D61, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA

Top