Volume 22, Number 6—June 2016

Dispatch

Prospective Validation of Cessation of Contact Precautions for Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase–Producing Escherichia coli1

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

After contact precautions were discontinued, we determined nosocomial transmission of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)–producing Escherichia coli by screening hospital patients who shared rooms with ESBL-producing E. coli–infected or –colonized patients. Transmission rates were 2.6% and 8.8% at an acute-care and a geriatric/rehabilitation hospital, respectively. Prolonged contact was associated with increased transmission.

The rapid increase of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)–producing Enterobacteriaceae has challenged healthcare facilities worldwide regarding implementation of effective infection-control measures to limit further nosocomial spread (1). The benefits of routine enforcement of contact precautions must be balanced against additional costs, impediments to patient care, and exposure to ESBL-producing E. coli outside healthcare institutions.

At the University Hospital Basel (UHB), a university-affiliated tertiary care center in Basel, Switzerland, transmission rates of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli are low in contact patients exposed to patients colonized or infected with ESBL-producing E. coli. This low transmission rate challenges the routine use of contact precautions in nonepidemic settings (2). Based on our findings and recent data suggesting that ESBL-producing E. coli is predominantly acquired in the community (3), we abandoned contact precautions for patients infected or colonized with ESBL-producing E. coli at the UHB and an affiliated long-term care center, Felix Platter Hospital (FPH), in Basel. To validate this practice, we screened all patients who shared a hospital room with a patient with ESBL-producing E. coli to determine transmission rates.

UHB is an acute-care hospital with 735 beds, of which 8.7% are in rooms with 4 beds and the remaining are in rooms with 1–2 beds. FPH is a university-affiliated geriatric and rehabilitation center with 320 beds, of which 47.5% are in rooms with 4 beds and 52.5% are in rooms with 1–2 beds. In both facilities, the average distance between beds is 2 m. The 2 institutions share an infection-control team and microbiology laboratory. The study was approved by the local ethics committee as part of the quality assurance program; informed consent was waived.

FPH and UHB abandoned routine contact precautions for patients infected or colonized with ESBL-producing E. coli beginning January and June 2012, respectively; patients were included in this study through December 2013. We defined index patients as patients colonized or infected with an ESBL-producing E. coli in any specimen from any body site and contact patients as patients hospitalized for at least 24 hours in the same room as an index patient. Contact time was defined as the time index and contact patients shared a room before the contact patient was screened. Contact patients were prospectively screened once before discharge by swab sampling of the rectum and any open wounds or drainage sites; if Foley catheters were used, urine was also sampled and cultured. Transmission was considered to have occurred if ESBL screening results for the contact patient were positive and molecular typing by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) showed that the strain shared identity with the strain of the index patient.

We used standard culture methods with chromogenic medium (chromID ESBL; bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) to detect ESBL-producing E. coli. We performed routine identification and susceptibility testing using the Vitek 2 System (bioMérieux, Durham, NC, USA) with cefpodoxime, ceftriaxone, and ceftazidime. We confirmed positive results by using Etest strips (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile) containing cefotaxime or ceftazidime, with and without clavulanic acid. We used molecular typing by PFGE to determine the identity of strains.

We used the Fisher exact test and the Mann-Whitney U test for univariable comparisons. Logistic regression was performed to calculate odds ratios for transmission. Two-sided p<0.05 was considered significant.

During the study period, 231 contact patients (151 from UHB, and 80 from FPH) were exposed to 211 index patients (178 from UHB, 33 from FPH). Contact patients were screened for ESBL-producing E. coli after a median contact time of 4 (interquartile range 3–6) days at UHB and 15 (interquartile range 9–23) days at FPH.

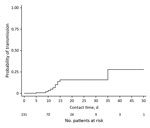

We recovered ESBL-producing E. coli from 24 contact patients (12 from each institution) and confirmed strain identity for 11, accounting for an overall transmission rate of 4.8% (11/231) (Figure 1). Transmission occurred in 2.6% (4/151) of contacts at UHB and 8.8% (7/80) at FPH (p = 0.052). We found no differences between contact patients with and without transmission of ESBL-producing E. coli in regard to baseline characteristics; use of antimicrobial drugs; or exposure to index patients, except for contact time, which was longer for patients with transmission (Table). Exposure to an index patient for >5 days was associated with increased odds for transmission (odds ratio 10.18, 95% CI 1.28–80.91; p = 0.028) (Figure 2).

After contact precautions for ESBL-producing E. coli were discontinued at the 2 hospitals in this study, transmissions occurred in 2.6% of contact patients at UHB and in 8.8% of contact patients at FPH. Transmissions were associated with duration of hospitalization in the same room as an index patient. At UHB, the rate of transmissions was similar to that reported during the period before discontinuation of contact precaution measures (1.5%) (2). At other Swiss acute-care hospitals, ESBL-producing E. coli transmission has affected 4.5% of all contact patients (3), and transmission of all ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae has affected 2.8%, despite implementation of contact precautions (4). The proportion of contact patients with transmission at FPH (8.8%) compares well with the proportion reported from similar settings (6.5%) (5).

Our finding that the transmission rate at the acute-care hospital was similar before and after discontinuation of contact precaution measures may be explained by high adherence to standard precautions (6), especially hand hygiene, for which compliance exceeded 90% (7), and the mainly short-term hospitalizations (<5 days). Thus, these findings may not be generalizable to other settings, especially when longer hospitalization is required, as is the case in geriatric/rehabilitation centers. Other factors may also have influenced transmission rates in our study, impeding generalizability of the findings to other countries. For example, the European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption Network (http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/antimicrobial_resistance/esac-net-database/Pages/database.aspx) reports that antimicrobial drug use in hospitals in Switzerland (1.9 defined daily doses/1,000 inhabitants/day) is lower than that in hospitals in other European countries (mean of 2.0 defined daily doses/1,000 inhabitants/day). Furthermore, the incidence of ESBL-producing E. coli may be lower in Switzerland than in other European countries (8), as suggested by a lower proportion (8.2%) of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli among invasive isolates in Switzerland as compared with those in other European countries (http://www.anresis.ch/index.php/anresisch-data-de.html).

Person-to-person transmission may play a substantial role in sustaining the global ESBL epidemic. In nursing homes, ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from residents living in adjacent rooms were found to be closely genetically related (9), and high ESBL-producing E. coli transmission rates (23%) have been reported in households (3), supporting our results that sustained contact over longer periods may facilitate transmission. Furthermore, patients hospitalized in the FPH may require more care, resulting in increased contact between healthcare workers and patients, possibly facilitating transmission (5).

In our study, contacts were screened only once before discharge, long-term surveillance for acquisition was not performed, and preenrichment of rectal swab samples was not conducted, all of which may have led to an underestimation of ESBL-producing E. coli cases. However, the circulation of ESBL-producing clones in the community may have resulted in an overestimation of transmission; before hospitalization, contact patients may have been colonized with strains in the community identical to those of index patients with whom they eventually shared a room. We acknowledge that our study lacks the robustness of a cluster-randomized trial to evaluate the effect of contact precautions on ESBL-producing E. coli transmission. However, we found that, when exposure times are short and adherence to standard precautions is high, the discontinuance of contact precautions for ESBL-producing E. coli in healthcare settings results in transmission rates similar to those observed when contact precautions are used.

Dr. Tschudin-Sutter is a senior physician and co-head of the consultancy service at the Division of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiology of the University Hospital Basel. Her primary research interests include prevention of hospital-acquired infections and transmission of pathogens in healthcare settings.

Acknowledgment

We thank Elisabeth Schultheiss for competently typing ESBL-producing E. coli isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

References

- Peleg AY, Hooper DC. Hospital-acquired infections due to gram-negative bacteria. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1804–13. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tschudin-Sutter S, Frei R, Dangel M, Stranden A, Widmer AF. Rate of transmission of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Enterobacteriaceae without contact isolation. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1505–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hilty M, Betsch BY, Bogli-Stuber K, Heiniger N, Stadler M, Kuffer M, Transmission dynamics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Enterobacteriaceae in the tertiary care hospital and the household setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:967–75. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fankhauser C, Zingg W, Francois P, Dharan S, Schrenzel J, Pittet D, Surveillance of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase–producing Enterobacteriaceae in a Swiss tertiary care hospital. Swiss Med Wkly. 2009;139:747–51 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Adler A, Gniadkowski M, Baraniak A, Izdebski R, Fiett J, Hryniewicz W, Transmission dynamics of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli clones in rehabilitation wards at a tertiary care centre. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:E497–505. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L; Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35:S65–164. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tschudin-Sutter S, Sepulcri D, Dangel M, Schuhmacher H, Widmer AF. Compliance with the World Health Organization hand hygiene technique: a prospective observational study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36:482–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kaier K, Frank U, Hagist C, Conrad A, Meyer E. The impact of antimicrobial drug consumption and alcohol-based hand rub use on the emergence and spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing strains: a time-series analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:609–14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Andersson H, Lindholm C, Iversen A, Giske CG, Ortqvist A, Kalin M, Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in residents of nursing homes in a Swedish municipality: healthcare staff knowledge of and adherence to principles of basic infection prevention. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44:641–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Table

Cite This Article1Preliminary results from this study were presented at the 25th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases; April 25–28, 2015; Copenhagen, Denmark.

Table of Contents – Volume 22, Number 6—June 2016

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Sarah Tschudin-Sutter, Division of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiology, University Hospital Basel, Petersgraben 4, CH-4031 Basel, Switzerland

Top