Maguari Virus Associated with Human Disease

Allison Groseth, Veronica Vine, Carla Weisend, Carolina Guevara, Douglas Watts

1, Brandy Russell, Robert B. Tesh, and Hideki Ebihara

Author affiliations: Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Greifswald–Insel Riems, Germany (A. Groseth); National Institutes of Health, Hamilton Montana, USA (A. Groseth, V. Vine, C. Weisend, H. Ebihara); US Naval Medical Research Unit 6, Lima, Peru (C. Guevara, D. Watts); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Ft. Collins, Colorado, USA (B. Russell); University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA (R.B. Tesh); Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA (H. Ebihara)

Main Article

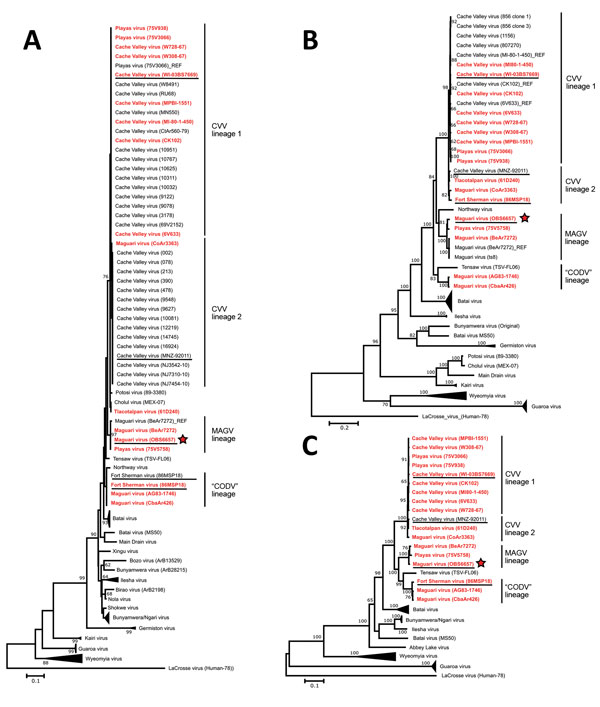

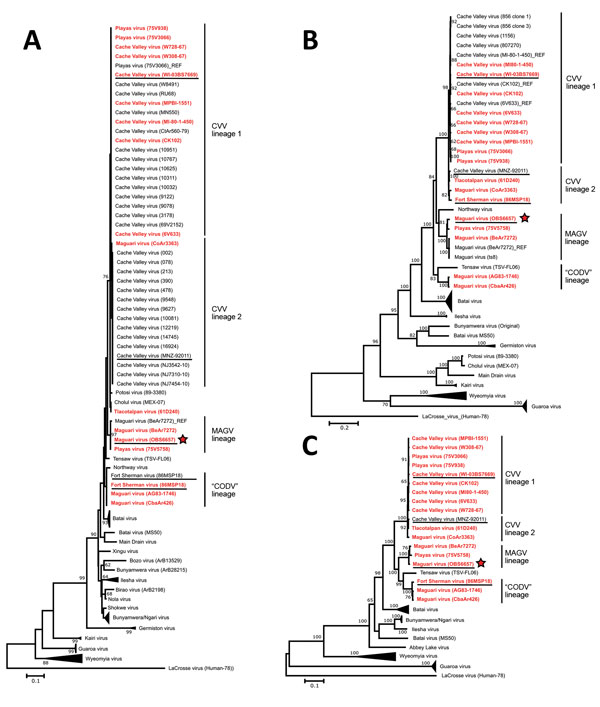

Figure 2

Figure 2. Phylogenetic relationship of MAGV-like isolate OBS6657 to other MAGV and CVV isolates and reference orthobunyaviruses. Maximum-likelihood trees (Jones, Taylor, and Thornton model, gamma-distributed) were constructed on the basis of the amino acid sequences of the nucleoprotein (A), glycoprotein (B), and polymerase (C). Bootstrap values based on 1,000 replicates are indicated for values >60. Sequences generated in this study are shown in red bold. Human isolates within the CVV, MAGV, and Córdoba virus clades are underlined, and the OBS6657 isolate is indicated with a red star. Scale bars indicate nucleotide substitutions per site. CVV, Cache Valley virus; CODV, Córdoba virus; MAGV, Maguari virus.

Main Article

Page created: July 17, 2017

Page updated: July 17, 2017

Page reviewed: July 17, 2017

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.