Volume 24, Number 1—January 2018

Dispatch

Expected Duration of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes after Zika Epidemic

Figure 1

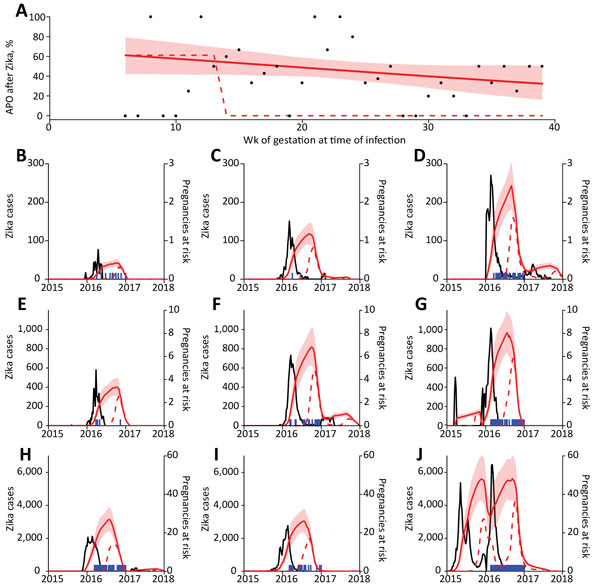

Figure 1. Relationship between Zika virus infection and expected related APOs per 1,000 pregnancies in Brazil during April 2015–July 2017. A) Percentage of APOs (fetal loss at any gestational age, stillbirth, neonatal abnormality) given symptomatic PCR-confirmed Zika virus infection. Points show weekly proportion with APO (4); red line indicates fit to data with a generalized linear model, and shading indicates 95% CIs; dashed line indicates fixed risk in first trimester only (5). B–J) Blue lines indicate suspected Zika cases in different regions; red lines indicate expected number of births with Zika-associated APO in subsequent weeks based on the 2 risk distributions in panel A. Shaded regions indicate 95% CIs. Model assumes 17% of Zika virus infections are reported (5,6). APO, adverse pregnancy outcome.

References

- Kleber de Oliveira W, Cortez-Escalante J, De Oliveira WTGH, do Carmo GMI, Henriques CMP, Coelho GE, et al. Increase in reported prevalence of microcephaly in infants born to women living in areas with confirmed Zika virus transmission during the first trimester of pregnancy—Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:242–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Johansson MA, Mier-y-Teran-Romero L, Reefhuis J, Gilboa SM, Hills SL. Zika and the risk of microcephaly. [Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2016;375:498]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- França GVA, Schuler-Faccini L, Oliveira WK, Henriques CMP, Carmo EH, Pedi VD, et al. Congenital Zika virus syndrome in Brazil: a case series of the first 1501 livebirths with complete investigation. Lancet. 2016;388:891–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brasil P, Pereira JP Jr, Moreira ME, Ribeiro Nogueira RM, Damasceno L, Wakimoto M, et al. Zika virus infection in pregnant women in Rio de Janeiro. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2321–34. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cauchemez S, Besnard M, Bompard P, Dub T, Guillemette-Artur P, Eyrolle-Guignot D, et al. Association between Zika virus and microcephaly in French Polynesia, 2013-15: a retrospective study. Lancet. 2016;387:2125–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kucharski AJ, Funk S, Eggo RM, Mallet H-P, Edmunds WJ, Nilles EJ. Transmission dynamics of Zika virus in island populations: a modelling analysis of the 2013–14 French Polynesia outbreak. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004726. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Martinez ME. Preventing Zika virus infection during pregnancy using a seasonal window of opportunity for conception. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002520. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Duffy MR, Chen T-H, Hancock WT, Powers AM, Kool JL, Lanciotti RS, et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2536–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Honein MA, Dawson AL, Petersen EE, Jones AM, Lee EH, Yazdy MM, et al.; US Zika Pregnancy Registry Collaboration. Birth defects among fetuses and infants of US women with evidence of possible Zika virus infection during pregnancy. JAMA. 2017;317:59–68. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- van der Linden V, Pessoa A, Dobyns W, Barkovich AJ, Júnior HV, Filho ELR, et al. Description of 13 infants born during October 2015–January 2016 with congenital Zika virus infection without microcephaly at birth—Brazil. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1343–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pacheco O, Beltrán M, Nelson CA, Valencia D, Tolosa N, Farr SL, et al. Zika virus disease in Colombia—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2016;NEJMoa1604037. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- de Oliveira WK, Carmo EH, Henriques CM, Coelho G, Vazquez E, Cortez-Escalante J, et al. Zika virus infection and associated neurologic disorders in Brazil. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1591–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brito CA, Brito CC, Oliveira AC, Rocha M, Atanásio C, Asfora C, et al. Zika in Pernambuco: rewriting the first outbreak. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2016;49:553–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reefhuis J, Gilboa SM, Johansson MA, Valencia D, Simeone RM, Hills SL, et al. Projecting month of birth for at-risk infants after Zika virus disease outbreaks. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:828–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Aragao MFVV, Holanda AC, Brainer-Lima AM, Petribu NCL, Castillo M, van der Linden V, et al. Nonmicrocephalic infants with congenital Zika syndrome suspected only after neuroimaging evaluation compared with those with microcephaly at birth and postnatally: how large is the Zika virus “iceberg”? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38:1427–34. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar