Volume 25, Number 3—March 2019

Research

Utility of Whole-Genome Sequencing to Ascertain Locally Acquired Cases of Coccidioidomycosis, Washington, USA

Figure

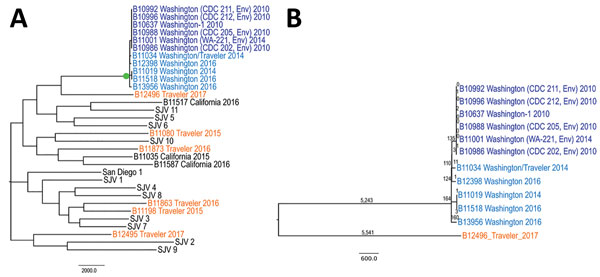

Figure. Genetic relationships among Coccidioides immitis isolates. A) Isolates from patients in Washington, USA, compared with isolates from other locations. B) Genetic relationships among C. immitis isolates from the Washington clade; single-nucleotide polymorphism numbers are shown above the branches. Dark blue indicates previously described environmental and human isolates (13) from Washington, light blue indicates isolates from new cases that were likely acquired in Washington, and orange indicates isolates from cases that were likely acquired outside Washington. Isolates from patients with the documented travel histories are indicated as Traveler. Travel history is detailed in the Table. Isolates with SJV names are from the San Joaquin Valley, California, as described (20). Bootstrap values shown in green circle indicate 100% support. Scale bars indicate nucleotide substitutions per site. CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Env, environment.

References

- Brown J, Benedict K, Park BJ, Thompson GR III. Coccidioidomycosis: epidemiology. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:185–97.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Adams D, Fullerton K, Jajosky R, Sharp P, Onweh D, Schley A, et al. Summary of notifiable infectious diseases and conditions—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;62:1–122.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cordeiro RA, Brilhante RS, Rocha MF, Bandeira SP, Fechine MA, de Camargo ZP, et al. Twelve years of coccidioidomycosis in Ceará State, Northeast Brazil: epidemiologic and diagnostic aspects. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;66:65–72.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wilken JA, Sondermeyer G, Shusterman D, McNary J, Vugia DJ, McDowell A, et al. Coccidioidomycosis among workers constructing solar power farms, California, USA, 2011–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1997–2005.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pappagianis D; Coccidioidomycosis Serology Laboratory. Coccidioidomycosis in California state correctional institutions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:103–11.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Colson AJ, Vredenburgh L, Guevara RE, Rangel NP, Kloock CT, Lauer A. Large-scale land development, fugitive dust, and increased coccidioidomycosis incidence in the antelope valley of California, 1999–2014. Mycopathologia. 2017;182:439–58.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Marsden-Haug N, Goldoft M, Ralston C, Limaye AP, Chua J, Hill H, et al. Coccidioidomycosis acquired in Washington State. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:847–50.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Galgiani JN, Thompson G III. Valley fever (coccidioidomycosis), tutorial for primary care professionals, 2016. Valley Fever Center for Excellence, The University of Arizona [cited 2018 Nov 30]. https://vfce.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/9-valley_fever_tutorial.pdf

- Arizona Department of Health Services (AZDoH). Valley fever 2016 annual report, 2017 [cited 2018 Nov 30]. https://www.azdhs.gov/documents/preparedness/epidemiology-disease-control/valley-fever/reports/valley-fever-2016.pdf

- Cooksey GS, Nguyen A, Knutson K, Tabnak F, Benedict K, McCotter O, et al. Notes from the field: increase in coccidioidomycosis—California, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:833–4.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gorris M, Cat L, Zender C, Treseder K, Randerson J. Coccidioidomycosis dynamics in relation to climate in the southwestern United States. GeoHealth. 2018;2:6–24.

- Marsden-Haug N, Hill H, Litvintseva AP, Engelthaler DM, Driebe EM, Roe CC, et al.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Coccidioides immitis identified in soil outside of its known range - Washington, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:450.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Litvintseva AP, Marsden-Haug N, Hurst S, Hill H, Gade L, Driebe EM, et al. Valley fever: finding new places for an old disease: Coccidioides immitis found in Washington State soil associated with recent human infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:e1–3.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Washington State Department of Health (WADoH). Washington State annual report on fungal disease, 2014 [cited 2018 Nov 30]. https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/5100/420-146-FungalDiseaseAnnualReport.pdf

- Barker BM, Jewell KA, Kroken S, Orbach MJ. The population biology of coccidioides: epidemiologic implications for disease outbreaks. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:147–63.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Neafsey DE, Barker BM, Sharpton TJ, Stajich JE, Park DJ, Whiston E, et al. Population genomic sequencing of Coccidioides fungi reveals recent hybridization and transposon control. Genome Res. 2010;20:938–46.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fisher MC, Rannala B, Chaturvedi V, Taylor JW. Disease surveillance in recombining pathogens: multilocus genotypes identify sources of human Coccidioides infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9067–71.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fisher MC, Koenig GL, White TJ, Taylor JW. Pathogenic clones versus environmentally driven population increase: analysis of an epidemic of the human fungal pathogen Coccidioides immitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:807–13.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Teixeira MM, Barker BM. Use of population genetics to assess the ecology, evolution, and population structure of Coccidioides. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1022–30.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Engelthaler DM, Roe CC, Hepp CM, Teixeira M, Driebe EM, Schupp JM, et al. Local population structure and patterns of Western Hemisphere dispersal for Coccidioides spp., the fungal cause of Valley fever. MBio. 2016;7:e00550–16.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Salipante SJ, SenGupta DJ, Cummings LA, Land TA, Hoogestraat DR, Cookson BT. Application of whole-genome sequencing for bacterial strain typing in molecular epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:1072–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Allard MW, Bell R, Ferreira CM, Gonzalez-Escalona N, Hoffmann M, Muruvanda T, et al. Genomics of foodborne pathogens for microbial food safety. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2018;49:224–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gardy JL, Loman NJ. Towards a genomics-informed, real-time, global pathogen surveillance system. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19:9–20.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease and Prevention. Coccidioidomycosis/Valley fever (Coccidioides spp.), 2011. Case definition. CSTE position statement. 10-ID-04 [cited 2018 Nov 30] https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/coccidioidomycosi s/case-definition/2011

- Etienne KA, Roe CC, Smith RM, Vallabhaneni S, Duarte C, Escadon P, et al. Whole-genome sequencing to determine origin of multinational outbreak of Sarocladium kiliense bloodstream infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:476–81.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sahl JW, Lemmer D, Travis J, Schupp JM, Gillece JD, Aziz M, et al. NASP: an accurate, rapid method for the identification of SNPs in WGS datasets that supports flexible input and output formats. Microb Genom. 2016;2:e000074.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Li H. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2987–93.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vakatov D. The NCBI C++ toolkit book, 2004. National Center for Biotechnology Information [cited 2018 Nov 30]. https://ncbi.github.io/cxx-toolkit

- Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, et al. Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e115.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Valdivia L, Nix D, Wright M, Lindberg E, Fagan T, Lieberman D, et al. Coccidioidomycosis as a common cause of community-acquired pneumonia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:958–62.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chang DC, Anderson S, Wannemuehler K, Engelthaler DM, Erhart L, Sunenshine RH, et al. Testing for coccidioidomycosis among patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1053–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tartof SY, Benedict K, Xie F, Rieg GK, Yu KC, Contreras R, et al. Testing for coccidioidomycosis among community-acquired pneumonia patients, southern California, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:779–81.PubMedGoogle Scholar