Volume 25, Number 7—July 2019

Synopsis

Bacillus cereus–Attributable Primary Cutaneous Anthrax-Like Infection in Newborn Infants, India

Abstract

During March 13–June 23, 2018, anthrax-like cutaneous lesions attributed to the Bacillus cereus group of organisms developed in 12 newborns in India. We traced the source of infection to the healthcare kits used for newborn care. We used multilocus sequence typing to characterize the 19 selected strains from various sources in hospital settings, including the healthcare kits. This analysis revealed the existence of a genetically diverse population comprising mostly new sequence types. Phylogenetic analysis clustered most strains into the previously defined clade I, composed primarily of pathogenic bacilli. We suggest that the synergistic interaction of nonhemolytic enterotoxin and sphingomyelinase might have a role in the development of cutaneous lesions. The infection was controlled by removing the healthcare kits and by implementing an ideal housekeeping program. All the newborns recovered after treatment with ciprofloxacin and amikacin.

The Bacillus cereus group includes ecologically diverse gram-positive and endospore-forming bacilli that are ubiquitous in the environment. The prominent members of this group are B. wiedmanii, B. anthracis, B. cereus sensu lato, B. cereus sensu stricto, B. thuringiensis, B. weihenstephanensis, B. mycoides, B. pseudomycoides, B. cytotoxicus, and B. toyonensis. Because the endospores of these species can resist extreme environmental conditions and thermal treatments, they are difficult to eliminate from processing chains of healthcare products and from clinical settings (1). The pathogenic potential of the B. cereus group varies from strains used as probiotics in animal feed to lethal and highly toxic strains (2,3). Thus, determining the degree to which pathogenic strains can be distinguished from nonpathogenic strains is essential.

B. cereus is well-known as a foodborne pathogen. In recent years, this bacterium was reported to cause several systemic and local nongastrointestinal infections in immunocompromised and immunocompetent persons (4,5). Specific populations, including intravenous drug abusers and patients with postsurgical or posttraumatic wounds, are at risk for these infections (6,7). In addition, numerous cases of fulminant infections similar to anthrax have been reported in healthy persons (8,9). Skin lesions of B. anthracis infection begin with a papule, which eventually becomes serosanguinous and develops a black eschar similar to some of the B. cereus skin lesions described by Henrickson et al. (10). Infections caused by B. cereus in newborns have been reported occasionally (11,12). We describe a cluster of 12 cases of severe anthrax-like cutaneous infections in otherwise healthy newborns attributed to the B. cereus group.

Case Study and Investigation

The Assam Medical College & Hospital (AMCH) is a tertiary care hospital in Dibrugarh, Assam, in northeasernt India. During March 13–June 23, 2018, extensive cutaneous vesicles or bullous lesions, mostly on the face, neck, and arm, developed in 12 newborns (8 boys, 4 girls); gas gangrene–like lesions eventually developed in 2 of the infants (Figure 1). All had been born healthy. All 12 newborns had a positive indication of sepsis. The initial clinical diagnosis was early-onset sepsis with staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Retrospectively, when records of these cases were analyzed, blood cultures were sterile or had growth of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus aureus.

This investigation focused on the labor room and the attached baby room because skin lesions developed within a few hours after delivery. Samples from exposed healthcare products, including the healthcare kits that contained items used during delivery, were cultured in nutrient broth and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Upon confirmation of visible growth in nutrient broth, the samples were subcultured in blood and nutrient agar and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Hand swab samples from hospital staff and the environment were cultured both aerobically and anaerobically. We obtained samples from the skin, armpit, and umbilical cord stump of newborns just after delivery at 2-day intervals. All samples from infants, staff, and the environment showed substantial growth of Bacillus species. All the bacteriology work was conducted in a Biosafety Level 3 laboratory. The institutional ethics committee (human) of AMCH approved this study.

Intervention

On May 19, 2018, after confirmation of B. cereus group in the healthcare kits, the infection control officer from the AMCH Department of Microbiology advised using these kits only after they were autoclaved in a validated steam autoclave and terminal cleaning (i.e., extensive cleaning of all detachable objects in the room, cleaning of air duct surfaces in the ceiling, and thorough cleaning of everything downward to the floor) of the labor and the attached baby room was performed. However, on June 23, the same type of lesion developed in another newborn. When B. cereus outbreaks occur, obtaining control is difficult because these bacilli can survive long periods in the environment and are resistant to many commonly used sanitizing agents (13). After the June 23 case, an extensive terminal cleaning of the unit was done, along with staff training on appropriate housekeeping practices. All the instruments and containers were autoclaved, and surfaces were cleaned in 2 steps: first, with alkaline detergents, then with a disinfectant (D-125, Microgen, http://microgenindia.co). Beds were manually cleaned with detergent and water followed by heat treatment. Rooms were fogged with a sporicidal disinfectant containing hydrogen peroxide and silver nitrate (ECOSHIELD; Johnson & Johnson, https://www.jnj.com). All the healthcare kits were removed, and staff were advised to discontinue their use. Since June 23, 2018, no additional cases have been reported.

Identification of B. cereus Group

Based on the colony characteristics, β-hemolysis in blood agar, motility, production of lecithinase in egg yolk media, inability to ferment mannitol, and penicillin resistance, the isolates were designated as B. cereus. We subjected 4 representative strains to sequencing using the universal primer PF (5′-AGAGTTTGATCATGGCTCAG-3′) and PR (5′-GGACTACCAGGGTATCTAAT-3′) for the 16s rRNA gene (14).

PCR Detection of Toxin-Encoding Genes

We performed PCR detection for toxins (cytK, nheA, nheB, nheC, hblA, hblC, hblD, entFM, pi-plc, and sph) and plasmid-encoding B. anthracis virulence factors (cap, lef pag, and cya) encoding genes. The primer sequences used for PCR are listed in the Appendix Table.

Multilocus Sequence Typing Data Analysis

We selected 19 strains for molecular characterization. We used the B. cereus multilocus sequence typing (MLST) website (https://pubmlst.org/bcereus) that contains the partial sequences of the 7 housekeeping genes (glp, gmk, ilv, pta, pur, pyc, and tpi) (15). We conducted Sanger sequencing using Genetic Analyzer 3500 (Applied Biosystems, https://www.thermofisher.com). We compared the allele sequences with those available in the MLST database for assignment of allele numbers and sequence type (ST). We submitted all new alleles, MLST profiles (STs), and isolates to the MLST database. We obtained the population snapshot of the 1,795 STs available in the MLST database using goeBURST implemented in Phyloviz 2.0 using the default single-locus variant level (sharing at least 6/7 alleles) (16). The goeBURST Full MST (minimum spanning tree; http://www.phyloviz.net/goeburst) was done to identify BURST groups (BGs) among the STs identified in this study.

Phylogenetic Analysis

The concatenated MLST sequences available at the MLST database were used for constructing maximum-likelihood trees. We used RAxML version 8 (17) implemented in RDP4 version 4.66 (18) with the GTRCAT model and a bootstrap resampling of 1,000 replicates.

Diversity and Recombination Analysis

We calculated the length of each MLST locus, number of alleles, average nucleotide diversity (π), and number of polymorphic sites using DnaSP version 6.11.01 (19) based on the allelic sequences of the STs. We calculated the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitutions (dN/dS) to determine the selective pressure at each locus using the Nei and Gojobori method in START2 (20). The parameters dN and dS indicated average nonsynonymous and synonymous substitutions per site, respectively.

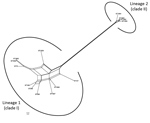

We conducted phylogenetic network analysis using Splits Tree version 4 (21) to identify lineages and recombination events within and across the lineages. We constructed the Splits Tree networks based on the concatenated sequences of STs using the neighbor-net algorithm with bootstrap resampling of 1,000 replicates. The resulting networks were analyzed using pairwise homoplasy index (PHI) test implemented in Splits Tree. A p value <0.05 indicated significant evidence of recombination.

We evaluated the linkage disequilibrium for the allelic data using LIAN version 3.7 (http://guanine.evolbio.mpg.de/cgi-bin/lian/lian.cgi.pl/query) (22). The standardized index of association (IAS) used for estimating linkage disequilibrium between alleles of the 7 MLST loci was calculated using the Monte Carlo method with 10,000 burn-in iterations. The IAS values >0 and p<0.05 indicated significant linkage disequilibrium.

Population Structure and BURST Group

MLST identified 14 STs among the selected 19 strains, including 5 predefined STs (ST75, ST127, ST266, ST380, and ST1465) and 9 new STs (ST1659, ST1660, ST1661, ST1662, ST1663, ST1664, ST1665, ST1667 and ST1668). Most (64.3%) identified STs were new.

The B. cereus MLST database clusters the available 1,795 STs into 10 major clonal complexes (CCs); a CC is a group of STs defined by goeBURST using the stringent group definition of single-locus variant level. The population snapshot obtained using goeBURST identified 3 STs (ST1465, ST1662, and ST1663) from the ST142 CC and 1 ST (ST75) from ST365 CC among the 14 STs identified in this study (Figure 2). The remaining STs were not a part of these major CCs. With a less stringent group definition of double-locus variant (DLV, sharing at least 5/7 alleles) or triple-locus variant (TLV, sharing at least 4/7 alleles) level, all of the STs in a goeBURST group cannot be considered as members of a single CC and hence referred to as BGs in our study. The goeBURST full MST analysis using the 14 STs from this study identified 3 BGs at TLV level (sharing at least 4/7 alleles) (Figure 3). The BG1 with ST1465, ST1662, ST1664, and ST1665 comprised strains from storage facilities and healthcare kits with ST1662 assigned as the putative primary founder. The BG2 included STs 266, 380, and 1661 with ST380 assigned as the putative primary founder. The BG2 consisted of strains from skin colonizers, umbilical cord stump, healthcare kits, and cutaneous lesions. The doubleton BG3 consisted of ST1660 and ST1665 with isolates recovered from healthcare kits and cutaneous lesions. We identified 5 singletons (not linked to any other ST): ST75, ST127, ST1659, ST1662, and ST1668.

Phylogenetic Origin of the Strains

The taxonomic identification of the 14 STs found in this study was done by constructing a phylogenetic tree with 18 B. cereus group species type strains (Figure 4). To illustrate the virulence potential of the strains, we constructed a phylogenetic tree (Figure 5) using the 14 STs from this study along with 38 STs representing 55 virulent isolates of B. cereus based on the selection made by Hoffmaster et al. (23). The STs clustered into 3 phylogenetic clades and were named to be consistent with previously defined phylogenetic clades by Priest et al. (24). Among the 14 STs we identified, 10 STs representing 14 strains were assigned to clade I, which comprised primarily pathogenic bacilli and mostly represented strains from healthcare kit and cutaneous lesion (24). Out of the 10 STs, 3 STs clustered into the cereus III/clade I lineage, 3 STs into a new cluster/clade I represented by ST144, 1 ST in cereus I/clade I lineage, and 2 STs in cereus II (emetic)/clade I lineage. None of the clade I–designated 10 STs grouped into the cereus IV lineage. Clade II consisted of 4 STs representing 5 strains grouped in tolworthi/clade II lineage and were representing strains mostly from the environment. None of the 14 STs identified in this study clustered in clade III (others).

Distribution of Enterotoxins, Sphingomyelinase, and Phosphatidylinositol Phospholipase C Encoding Genes

The cytK, sph, and pi-plc genes encoding cytotoxin K, sphingomyelinase (SMase), and phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C (Pi-Plc), respectively, were commonly detected in 73.7% (n = 14) of the 19 selected strains, followed by nheA and nheC in 68.4% (n = 13), nheB in 52.6% (n = 10), and entFM in 42.1% (n = 8) (Table 1). Of the 14 strains previously designated to clade I, the nheABC gene complex (nheA, nheB, and nheC) encoding the nonhemolytic enterotoxin (Nhe) was detected in 8 strains and entFM gene encoding enterotoxin FM was also detected in 8 strains. None of the clade II assigned strains were detected positive for the nheABC gene complex and the entFM gene. The hbl gene complex (hblA, hblC, and hblD) encoding hemolysin BL (HBL) was found in only 1 strain designated to clade II, whereas none of the clade I–assigned strains harbored this complex (Table 2). Both hblA and hblC were detected in 1 each of the 19 strains. None of the strains were positive for genes encoding B. anthracis plasmid-mediated virulence factors (Table 1).

Sequence and Allelic Diversity

Sequence alignment of each of the 7 MLST loci showed no insertion or deletion with sizes ranging from 348 bp (pur) to 504 bp (gmk). The number of alleles at each locus ranged from 4 (gmk) to 11 (ilv and tpi). The dN/dS values indicate selective pressure on protein-coding genes; dN/dS >1 indicates positive and dN/dS <1 negative selective pressure. The dN/dS ratio for each locus varied from 0.0076 (ilv) to 0.0547 (pur), indicating strong negative/purifying selective pressure on these genes (Table 3).

Recombination Analysis

The Splits Tree network for the 14 STs representing the 19 selected strains identified 2 lineages among them (Figure 6). Lineage 1 comprised STs 75, 127, 266, 380, 1660, 1659, 1661, 1665, 1667, and 1668 previously designated to clade I. The STs 1465, 1662, 1663, and 1664 previously designated to clade II were in lineage 2. We observed extensive reticulations across the lineages and within lineage 1. The PHI test also provided significant evidence of recombination for the whole population (14 STs) and lineage 1 (p<0.05). However, the IAS values, for estimation of linkage disequilibrium, differed significantly from 0 for the entire population, as well as for the lineages, indicating the existence of linkage disequilibrium between the loci or a clonal population structure (Table 4).

MLST data analysis identified a genetically diverse population of 14 STs representing the 19 selected B. cereus strains because most of the STs were identified as new. Population snapshot using goeBURST illustrated the rare occurrences of clinical cases among the B. cereus group. Among the 14 STs, 3 were from the ST142 CC and 1 from the ST365 CC, indicating evolutionary descent from worldwide clones. The goeBURST Full MST analysis of the 14 STs identified only 3 BGs even at the TLV level; the rest were identified as singletons, which again illustrates the high genetic diversity. Most of the strains isolated from healthcare kits and cutaneous lesions were represented by new STs, suggesting that greater diversity was possibly because of adaptation to the new niche.

The phylogenetic origin of the 19 strains was determined to investigate whether any of the 14 STs representing these strains clustered into the previously described clade I, composed primarily of pathogenic bacilli (24). The clade I–designated 10 STs were distributed into various lineages of clade I and were closely related to the Anthracis lineage, as described by Hoffmaster et al. (23). Among them, ST1659, a new ST representing a strain isolated from a healthcare kit, had the closest relationship to the Anthracis lineage and shared the same gmk, pta, pur, and pyc alleles with the Ames anthracis strain (ST1). The ST75 isolate from ST365 CC, which has been reported earlier for representing a severe septicemic B. cereus strain, shared the same gmk and pta alleles with the B. anthracis strains (25).

Several studies have demonstrated that B. cereus isolates closely related to B. anthracis are of clinical rather than environmental origin (26,27). All the clade I–designated strains were negative for genes encoding B. anthracis virulence factors. Alternatively, these factors might not be necessary for severe nongastrointestinal infections because isolates from severe cases have been reported to be negative for plasmids (8). Most of the clade I–assigned STs represented strains recovered from healthcare kits, suggesting these strains might be responsible for cutaneous lesions. Three clade II–assigned STs were from ST142 CC, comprising mostly foodborne isolates with potential to cause foodborne illness (28). Hence, the potential role of the strains represented by these 3 STs in the development of cutaneous lesions is arguable.

Phylogenetic network analysis using Splits Tree identified 2 lineages among the 14 STs identified in this study. All the clade I–designated STs clustered in lineage 1, whereas all the clade II–designated STs clustered in lineage 2. Extensive reticulations in Splits Tree networks and PHI test provided significant evidence of recombination across the lineages and within lineage 2. Even though the IAS and dN/dS values predicted an overall clonal population structure, the high genetic diversity and recombination might have enabled the population to enhance fitness and survive.

To evaluate the interclade variability of toxin-encoding genes, we performed PCR detection of these genes. The nheABC gene complex and entFM gene were detected only among the clade I–designated strains, whereas none of the clade II–identified strains were positive for the nheABC gene complex and the entFM gene. The Nhe enterotoxin is considered to be the major virulence factor in B. cereus diarrheal disease (29). The synergistic interaction of Nhe and SMase in in vitro cytotoxicity has been demonstrated (30). All the members of the nheABC gene complex are required to form functional transmembrane pores for the entry of SMase into the epithelial cell membrane, otherwise inaccessible, and could result in cell membrane destabilization, as well as cell apoptosis through the ceramide intracellular signaling pathway (31,32). This case might be valid in our study because the clade I–designated strains harbored the nheABC gene complex, as well as the sph gene. Several findings have suggested that enterotoxin FM might be a potential cell wall peptidase involved in mutant bacterial shape, impairment in motility, and adhesion to eukaryotic cells and thus might be responsible for the virulence of the clade I–assigned strains because most of them harbored this gene (33). The hblA gene encoding the binding subunit C component and, hblC gene encoding the L2 lytic component sparsely detected among the 19 strains. The tripartite HBL enterotoxin requires all its components for maximum enterotoxic activity (34). Moreover, the cytK and hbl enterotoxin genes are often absent in B. cereus strains isolated from disease outbreaks, which argues against its potential role to elicit disease (35,36).

In this investigation, only 12 newborns were infected, even though the kits also were used for other newborns. Thus, development of nongastrointestinal infections in newborns is complex and might depend on factors such as the number of spores exposed, the presence of a virulent and avirulent cluster of microorganisms, toxin expression and interaction, and host conditions. Moreover, seasonal variation of increased count and germination of B. cereus spores in spring and summer have been reported (37–39). In this outbreak, lesions occurred during April in 6 newborns, May in 4, and March and June in 1 each. However, a thorough investigation is needed to understand the complexity of these infections. Our findings, along with previous reports, reinforce the idea that the members of the B. cereus group are underestimated emerging pathogens that can be involved in fatal nosocomial infections.

The cutaneous infections attributed to the B. cereus group in most of the cases in this study occurred in the exposed areas of the skin because they are often in contact with the environment and are prone to microscopic skin abrasions (39). The spores from the healthcare kits might have invaded the skin of newborns through these microscopic skin abrasions formed during baby cleaning (39). Moreover, vernix caseosa, a waxy substance covering the skin of newborns, often requires cleaning and might also be the cause of microscopic skin abrasions. Once in contact with skin, spores germinate and enterotoxin production occurs (39). In addition, toxicoinfection can occur because the kits contain all the items required to conduct labor, including contaminated gloves. Among the infants in this report, duration of labor ranged from 6 to 10 hours, so germination and toxin production might have occurred in the birth canal and accounted for the initial lesions that later extended from contact with the cleaning linens inside the kit and led to additional spore germination and toxin production.

Clinically, the lesions started as bullous or ruptured bullous lesions with extensive and rapidly spreading cellulitis. Two lesions eventually developed into gas gangrene–like infections as reported previously (4,40). However, in all 12 cases, blood culture was negative for B. cereus. Henrickson et al. reported the primary cutaneous infections caused by B. cereus in the absence of positive blood cultures (10,39). Extensive soft tissue involvement with gas gangrene infections in the first few newborns might have resulted from the initial use of β-lactam antimicrobial drugs because the existence of β-lactamase in sporulated Bacillus species has been predicted (41). All newborns recovered after treatment with ciprofloxacin and amikacin.

In conclusion, B. cereus primary cutaneous infection in newborns without bacteremia can occur from contaminated environments in hospitals. Bullous lesions or cellulitis during or just after delivery should be included in the differential diagnosis, and caution should be taken in initiating β-lactam antimicrobial drug treatment.

At the time of this study, Dr. Saikia was a professor in the Department of Microbiology, Gauhati Medical College & Hospital, Guwahati, India. She is currently a professor in the Department of Microbiology, Gauhati Medical College & Hospital, Guwahati, India. Her primary research interests are clinical microbiology, epidemiology of infectious diseases, healthcare-associated infections, and antimicrobial resistance.

Acknowledgment

We thank Biswajit Borkotoky for performing the initial Sanger sequencing of the 16s rRNA gene. We thank all the staff of Obstetrics and Gynecology, AMCH, for their cooperation and hospital administration for supporting this investigation.

References

- Mazas M, López M, Martínez S, Bernardo A, Martin R. Heat resistance of Bacillus cereus spores: effects of milk constituents and stabilizing additives. J Food Prot. 1999;62:410–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hong HA, Duc H, Cutting SM. The use of bacterial spore formers as probiotics. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:813–35. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Miller RA, Jian J, Beno SM, Wiedmann M, Kovac J. Intraclade variability in toxin production and cytotoxicity of Bacillus cereus group type strains and dairy-associated isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;84:e02479–17. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Darbar A, Harris IA, Gosbell IB. Necrotizing infection due to Bacillus cereus mimicking gas gangrene following penetrating trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:353–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Henrickson KJ. A second species of Bacillus causing primary cutaneous disease. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:19–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brett MM, Hood J, Brazier JS, Duerden BI, Hahné SJM. Soft tissue infections caused by spore-forming bacteria in injecting drug users in the United Kingdom. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:575–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Akesson A, Hedström SA, Ripa T. Bacillus cereus: a significant pathogen in postoperative and post-traumatic wounds on orthopaedic wards. Scand J Infect Dis. 1991;23:71–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hoffmaster AR, Ravel J, Rasko DA, Chapman GD, Chute MD, Marston CK, et al. Identification of anthrax toxin genes in a Bacillus cereus associated with an illness resembling inhalation anthrax. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8449–54. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Miller JM, Hair JG, Hebert M, Hebert L, Roberts FJ Jr, Weyant RS. Fulminating bacteremia and pneumonia due to Bacillus cereus. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:504–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Henrickson KJ, Shenep JL, Flynn PM, Pui CH. Primary cutaneous bacillus cereus infection in neutropenic children. Lancet. 1989;1:601–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gray J, George RH, Durbin GM, Ewer AK, Hocking MD, Morgan MEI. An outbreak of Bacillus cereus respiratory tract infections on a neonatal unit due to contaminated ventilator circuits. J Hosp Infect. 1999;41:19–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Patrick CC, Langston C, Baker CJ. Bacillus species infections in neonates. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:612–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sagripanti JL, Bonifacino A. Comparative sporicidal effects of liquid chemical agents. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:545–51.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ehresmann C, Stiegler P, Fellner P, Ebel JP. The determination of the primary structure of the 16S ribosomal RNA of Escherichia coli. 2. Nucleotide sequences of products from partial enzymatic hydrolysis. Biochimie. 1972;54:901–67. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jolley KA, Maiden MC. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:595. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Francisco AP, Vaz C, Monteiro PT, Melo-Cristino J, Ramirez M, Carriço JA. PHYLOViZ: phylogenetic inference and data visualization for sequence based typing methods. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:87. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Martin DP, Murrell B, Golden M, Khoosal A, Muhire B. RDP4: Detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 2015;1:

vev003 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Rozas J, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R, Dna SP. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2496–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jolley KA, Feil EJ, Chan MS, Maiden MC. Sequence type analysis and recombinational tests (START). Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1230–1. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Huson DH, Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:254–67. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Haubold B, Hudson RR. LIAN 3.0: detecting linkage disequilibrium in multilocus data. Linkage Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:847–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hoffmaster AR, Novak RT, Marston CK, Gee JE, Helsel L, Pruckler JM, et al. Genetic diversity of clinical isolates of Bacillus cereus using multilocus sequence typing. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:191. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Priest FG, Barker M, Baillie LWJ, Holmes EC, Maiden MCJ. Population structure and evolution of the Bacillus cereus group. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7959–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Barker M, Thakker B, Priest FG. Multilocus sequence typing reveals that Bacillus cereus strains isolated from clinical infections have distinct phylogenetic origins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;245:179–84. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hill KK, Ticknor LO, Okinaka RT, Asay M, Blair H, Bliss KA, et al. Fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis of Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:1068–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Helgason E, Okstad OA, Caugant DA, Johansen HA, Fouet A, Mock M, et al. Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis—one species on the basis of genetic evidence. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2627–30. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cardazzo B, Negrisolo E, Carraro L, Alberghini L, Patarnello T, Giaccone V. Multiple-locus sequence typing and analysis of toxin genes in Bacillus cereus food-borne isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:850–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Moravek M, Dietrich R, Buerk C, Broussolle V, Guinebretière MH, Granum PE, et al. Determination of the toxic potential of Bacillus cereus isolates by quantitative enterotoxin analyses. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;257:293–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Doll VM, Ehling-Schulz M, Vogelmann R. Concerted action of sphingomyelinase and non-hemolytic enterotoxin in pathogenic Bacillus cereus. PLoS One. 2013;8:

e61404 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Kolesnick RN, Goñi FM, Alonso A. Compartmentalization of ceramide signaling: physical foundations and biological effects. J Cell Physiol. 2000;184:285–300. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Haug TM, Sand SL, Sand O, Phung D, Granum PE, Hardy SP. Formation of very large conductance channels by Bacillus cereus Nhe in Vero and GH(4) cells identifies NheA + B as the inherent pore-forming structure. J Membr Biol. 2010;237:1–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tran S-L, Guillemet E, Gohar M, Lereclus D, Ramarao N. CwpFM (EntFM) is a Bacillus cereus potential cell wall peptidase implicated in adhesion, biofilm formation, and virulence. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:2638–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Beecher DJ, Macmillan JD. Characterization of the components of hemolysin BL from Bacillus cereus. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1778–84.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ehling-Schulz M, Guinebretiere MH, Monthán A, Berge O, Fricker M, Svensson B. Toxin gene profiling of enterotoxic and emetic Bacillus cereus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;260:232–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ehling-Schulz M, Svensson B, Guinebretiere MH, Lindbäck T, Andersson M, Schulz A, et al. Emetic toxin formation of Bacillus cereus is restricted to a single evolutionary lineage of closely related strains. Microbiology. 2005;151:183–97. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kmiha S, Aouadhi C, Klibi A, Jouini A, Béjaoui A, Mejri S, et al. Seasonal and regional occurrence of heat-resistant spore-forming bacteria in the course of ultra-high temperature milk production in Tunisia. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100:6090–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cheng VCC, Chen JHK, Leung SSM, So SYC, Wong S-C, Wong SCY, et al. Seasonal outbreak of Bacillus bacteremia associated with contaminated linen in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_2):S91–7.

- Bottone EJ. Bacillus cereus, a volatile human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:382–98. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gröschel D, Burgress MA, Bodey GP Sr. Gas gangrene-like infection with Bacillus cereus in a lymphoma patient. Cancer. 1976;37:988–91. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Saz AK. An introspective view of penicillinase. J Cell Physiol. 1970;76:397–403. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: June 10, 2019

1Current affiliation: Gauhati Medical College & Hospital, Guwahati, India.

Table of Contents – Volume 25, Number 7—July 2019

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Lahari Saikia, Gauhati Medical College & Hospital, Department of Microbiology, Guwahati, Assam, India

Top