Volume 27, Number 5—May 2021

Research

Genetic Evidence and Host Immune Response in Persons Reinfected with SARS-CoV-2, Brazil

Figure 2

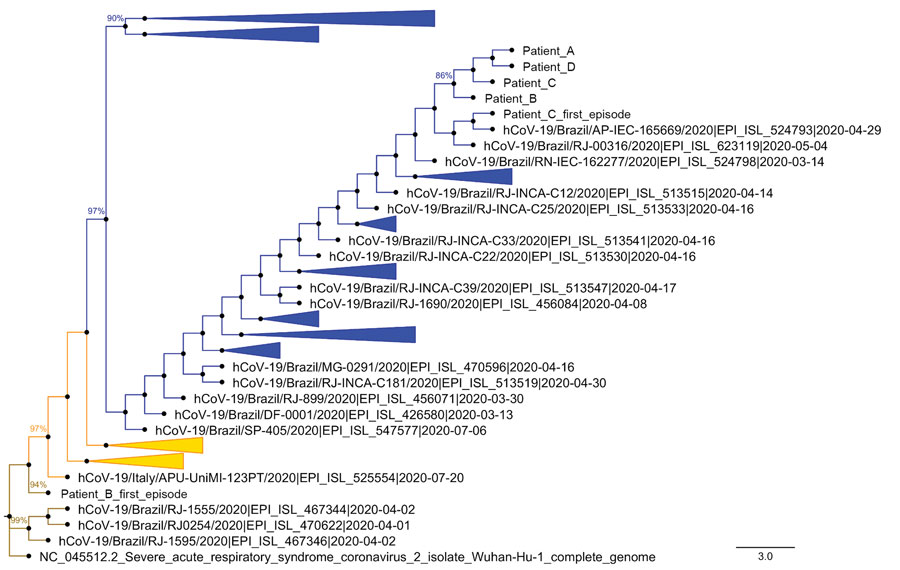

Figure 2. Phylogenetic analysis of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 genomes from reinfected patients, Brazil, 2020. Representative genomes deposited in GISAID (Appendix Table 1, Figure 3) were compared with sequences from virus genomes found in the respiratory samples from the first infection of patients B and C, and the second infection of patients A–D. A condensed phylogenetic tree rooted by reference genome Wuhan-Hu-1 (EPI_ISL_402125) was created with 1,000 bootstraps. Initial trees for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying neighbor-joining and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Jukes-Cantor model (24), and then selecting the topology with a superior log-likelihood value. The tree with the highest log likelihood (−46487.36) is shown. The final dataset included a total of 29,920 positions. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA version 7.0 (22,23). Evolutionary history was inferred using the maximum-likelihood method and Jukes-Cantor model. Brown represents the emerging clade 19A, orange the clade 20A, and blue the clade 20B. Scale bar indicates substitutions per site. hCoV, human coronavirus.

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 12]. https://covid19.who.int/

- Rodda LB, Netland J, Shehata L, Pruner KB, Morawski PA, Thouvenel CD, et al. Functional SARS-CoV-2-specific immune memory persists after mild COVID-19. Cell. 2021;184:169–183.e17. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases, data, and surveillance. 2020 [cited 2021 Feb 12]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/variant-surveillance/variant-info.html

- Hartley GE, Edwards ESJ, Aui PM, Varese N, Stojanovic S, McMahon J, et al. Rapid generation of durable B cell memory to SARS-CoV-2 spike and nucleocapsid proteins in COVID-19 and convalescence. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:

eabf8891 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Le Bert N, Tan AT, Kunasegaran K, Tham CYL, Hafezi M, Chia A, et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity in cases of COVID-19 and SARS, and uninfected controls. Nature. 2020;584:457–62. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ripperger TJ, Uhrlaub JL, Watanabe M, Wong R, Castaneda Y, Pizzato HA, et al. Detection, prevalence, and duration of humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2 under conditions of limited population exposure. Immunity. 2020;53:925–33. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hueston L, Kok J, Guibone A, McDonald D, Hone G, Goodwin J, et al. The antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:a387. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Edridge AWD, Kaczorowska J, Hoste ACR, Bakker M, Klein M, Loens K, et al. Seasonal coronavirus protective immunity is short-lasting. Nat Med. 2020;26:1691–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dan JM, Mateus J, Kato Y, Hastie KM, Yu ED, Faliti CE, et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science. 2021;371:

eabf4063 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Tillett RL, Sevinsky JR, Hartley PD, Kerwin H, Crawford N, Gorzalski A, et al. Genomic evidence for reinfection with SARS-CoV-2: a case study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:52–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- To KK-W, Hung IF-N, Ip JD, Chu AW-H, Chan W-M, Tam AR, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) reinfection by a phylogenetically distinct severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 strain confirmed by whole genome sequencing. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;•••:

ciaa1275 ; Epub ahead of print. DOIGoogle Scholar - Van Elslande J, Vermeersch P, Vandervoort K, Wawina-Bokalanga T, Vanmechelen B, Wollants E, et al. Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 reinfection by a phylogenetically distinct strain. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;•••:

ciaa1330 ; Epub ahead of print. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Prado-Vivar B, Becerra-Wong M, Guadalupe JJ, Marquez S, Gutierrez B, Rojas-Silva P, et al. COVID-19 reinfection by a phylogenetically distinct SARS-CoV-2 variant, first confirmed event in South America. SSRN. 2020 September 9 [cited 2021 Mar 19]. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Mulder M, van der Vegt DSJM, Oude Munnink BB, GeurtsvanKessel CH, van de Bovenkamp J, Sikkema RS, et al. Reinfection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in an immunocompromised patient: a case report. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;•••:

ciaa1538 ; Epub ahead of print. DOIGoogle Scholar - Selhorst P, Van Ierssel S, Michiels J, Mariën J, Bartholomeeusen K, Dirinck E, et al. Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 reinfection of a health care worker in a Belgian nosocomial outbreak despite primary neutralizing antibody response. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;•••:

ciaa1850 ; Epub ahead of print. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Larson D, Brodniak SL, Voegtly LJ, Cer RZ, Glang LA, Malagon FJ, et al. A case of early reinfection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Clin Infect Dis. 2020;•••:

ciaa1436 ; Epub ahead of print. DOIGoogle Scholar - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Research use only 2019-novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) real-time RT-PCR primers and probes. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 11]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/rt-pcr-panel-primer-probes.html

- Metsky HC, Matranga CB, Wohl S, Schaffner SF, Freije CA, Winnicki SM, et al. Zika virus evolution and spread in the Americas. Nature. 2017;546:411–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cleemput S, Dumon W, Fonseca V, Abdool Karim W, Giovanetti M, Alcantara LC, et al. Genome Detective Coronavirus Typing Tool for rapid identification and characterization of novel coronavirus genomes. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:3552–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Katoh K, Kuma K, Toh H, Miyata T. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:511–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–91. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jukes TH, Cantor CR. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Mammalian protein metabolism. Vol. III. Munro HN, editor. New York: Academic Press; 1969. p. 21–132.

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Candido DS, Claro IM, de Jesus JG, Souza WM, Moreira FRR, Dellicour S, et al.; Brazil-UK Centre for Arbovirus Discovery, Diagnosis, Genomics and Epidemiology (CADDE) Genomic Network. Evolution and epidemic spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Brazil. Science. 2020;369:1255–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Secretaria de Saúde do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Covid-19 monitoring panel in the Rio de Janeiro State [in Portuguese]. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 24]. http://painel.saude.rj.gov.br/monitoramento/covid19.html#

- Kiyuka PK, Agoti CN, Munywoki PK, Njeru R, Bett A, Otieno JR, et al. Human coronavirus NL63 molecular epidemiology and evolutionary patterns in rural coastal Kenya. J Infect Dis. 2018;217:1728–39 https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/217/11/1728/4948258. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Decaro N, Martella V, Saif LJ, Buonavoglia C. COVID-19 from veterinary medicine and one health perspectives: What animal coronaviruses have taught us. Res Vet Sci. 2020;131:21–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Neeland MR, Bannister S, Clifford V, Dohle K, Mulholland K, Sutton P, et al. Innate cell profiles during the acute and convalescent phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1084. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tay MZ, Poh CM, Rénia L, MacAry PA, Ng LFP. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:363–74. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sallenave J-M, Guillot L. Innate immune signaling and proteolytic pathways in the resolution or exacerbation of SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19: key therapeutic targets? Front Immunol. 2020;11:1229. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Groves DC, Rowland-Jones SL, Angyal A. The D614G mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Implications for viral infectivity, disease severity and vaccine design. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;538:104–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. 2020 [cited 2021 Feb 12]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/scientific-brief-emerging-variants.html

- Krafcikova P, Silhan J, Nencka R, Boura E. Structural analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 methyltransferase complex involved in RNA cap creation bound to sinefungin. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3717. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cottam EM, Whelband MC, Wileman T. Coronavirus NSP6 restricts autophagosome expansion. Autophagy. 2014;10:1426–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Choi B, Choudhary MC, Regan J, Sparks JA, Padera RF, Qiu X, et al. Persistence and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in an immunocompromised host. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2291–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Koyama T, Platt D, Parida L. Variant analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98:495–504. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kiyuka PK, Agoti CN, Munywoki PK, Njeru R, Bett A, Otieno JR, et al. Human coronavirus NL63 molecular epidemiology and evolutionary patterns in rural coastal Kenya. J Infect Dis. 2018;217:1728–39. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sun J, Xiao J, Sun R, Tang X, Liang C, Lin H, et al. Prolonged persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in body fluids. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1834–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- de la Rica R, Borges M, Gonzalez-Freire M. COVID-19: in the eye of the cytokine storm. Front Immunol. 2020;11:

558898 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Arunachalam PS, Wimmers F, Mok CKP, Perera RAPM, Scott M, Hagan T, et al. Systems biological assessment of immunity to mild versus severe COVID-19 infection in humans. Science. 2020;369:1210–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sekine T, Perez-Potti A, Rivera-Ballesteros O, Strålin K, Gorin J-B, Olsson A, et al.; Karolinska COVID-19 Study Group. Robust T cell immunity in convalescent individuals with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19. Cell. 2020;183:158–168.e14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar