Volume 27, Number 8—August 2021

Research

Effects of Patient Characteristics on Diagnostic Performance of Self-Collected Samples for SARS-CoV-2 Testing

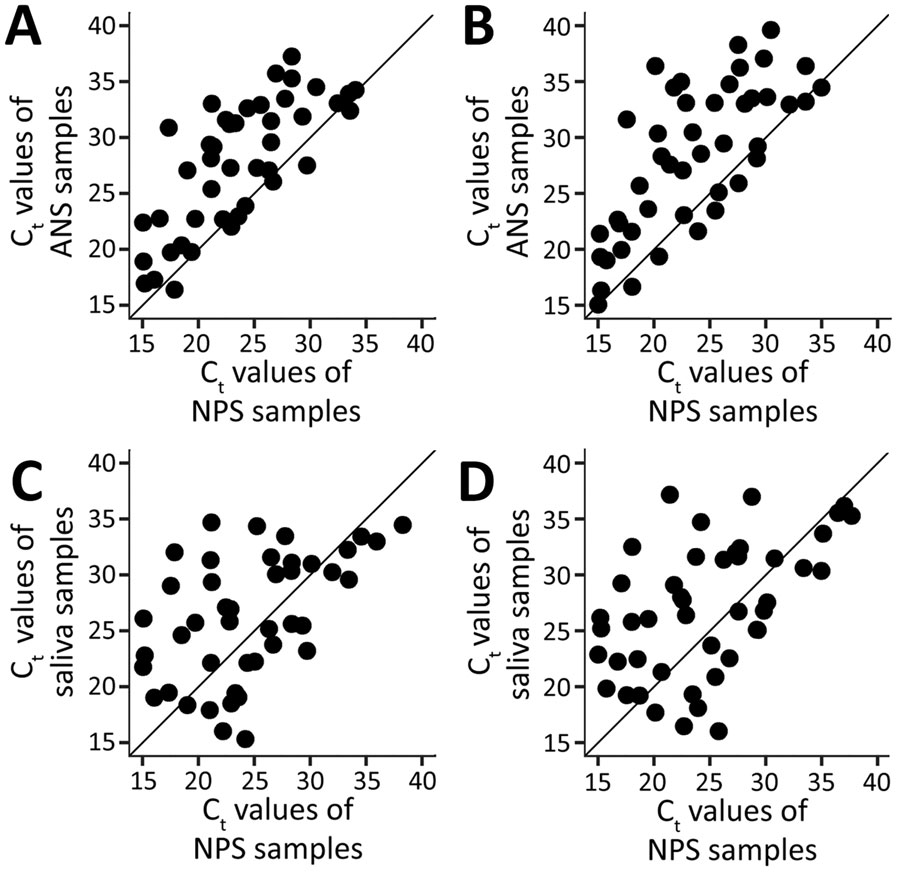

Figure 2

Figure 2. Ct values of self-collected and healthcare worker–collected samples for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 testing, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. PCR completed using CDC 2019-nCoV Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase PCR Diagnostic Panel (15). A) ANS and NPS samples at PCR target N1. B) ANS and NPS samples at PCR target N2. C) NPS and saliva samples at PCR target N1. D) NPS and saliva samples at PCR target N2. ANS, anterior nasal swab; Ct, cycle threshold; NPS, nasopharyngeal swab.

References

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 weekly epidemiological update—27 January 2021. 2021 Jan 27 [cited 2021 Feb 9]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update---27-january-2021

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidelines for collecting, handling, and testing clinical specimens for COVID-19. 2021 [cited 2021 Jan 29]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html

- Tu Y-P, Jennings R, Hart B, Cangelosi GA, Wood RC, Wehber K, et al. Swabs collected by patients or health care workers for SARS-CoV-2 testing. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:494–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McCormick-Baw C, Morgan K, Gaffney D, Cazares Y, Jaworski K, Byrd A, et al. Saliva as an alternate specimen source for detection of SARS-CoV-2 in symptomatic patients using Cepheid Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e01109–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Procop GW, Shrestha NK, Vogel S, Van Sickle K, Harrington S, Rhoads DD, et al. A direct comparison of enhanced saliva to nasopharyngeal swab for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in symptomatic patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e01946–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hanson KE, Barker AP, Hillyard DR, Gilmore N, Barrett JW, Orlandi RR, et al. Self-collected anterior nasal and saliva specimens versus health care worker-collected nasopharyngeal swabs for the molecular detection of SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e01824–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Payne DC, Smith-Jeffcoat SE, Nowak G, Chukwuma U, Geibe JR, Hawkins RJ, et al.; CDC COVID-19 Surge Laboratory Group. SARS-CoV-2 infections and serologic responses from a sample of U.S. Navy service members—USS Theodore Roosevelt, April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:714–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yousaf AR, Duca LM, Chu V, Reses HE, Fajans M, Rabold EM, et al. A prospective cohort study in nonhospitalized household contacts with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: symptom profiles and symptom change over time. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Jul 28 [Epub ahead of print].

- Buitrago-Garcia D, Egli-Gany D, Counotte MJ, Hossmann S, Imeri H, Ipekci AM, et al. Occurrence and transmission potential of asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections: A living systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17:

e1003346 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Sun J, Xiao J, Sun R, Tang X, Liang C, Lin H, et al. Prolonged persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in body fluids. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1834–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- COVID-19 Investigation Team. Clinical and virologic characteristics of the first 12 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States. Nat Med. 2020;26:861–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Grady Health System. Grady fast facts. 2018 [cited 2021 Jan 29]. https://www.gradyhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Grady_Fast_Facts.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How to collect your anterior nasal swab sample for COVID-19 testing. 2020 [cited 2021 Feb 12]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/testing/How-To-Collect-Anterior-Nasal-Specimen-for-COVID-19.pdf

- Lu X, Wang L, Sakthivel SK, Whitaker B, Murray J, Kamili S, et al. US CDC real-time reverse transcription PCR panel for detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1654–65. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Emergency use authorization: CDC 2019-nCoV Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel. 2020 [cited 2021 Mar 2]. https://www.fda.gov/media/134919/download

- Boehmer TK, DeVies J, Caruso E, van Santen KL, Tang S, Black CL, et al. Changing age distribution of the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, May–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1404–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Update to the standardized surveillance case definition and national notification for 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 29]. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cste.org/resource/resmgr/ps/positionstatement2020/Interim-20-ID-02_COVID-19.pdf

- World Health Organization. RSV surveillance case definitions. 2020 [cited 2021 January 29]; https://www.who.int/influenza/rsv/rsv_case_definition/en

- Altamirano J, Govindarajan P, Blomkalns AL, Kushner LE, Stevens BA, Pinsky BA, et al. Assessment of sensitivity and specificity of patient-collected lower nasal specimens for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 testing [Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3: e2014910]. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:

e2012005 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Kojima N, Turner F, Slepnev V, Bacelar A, Deming L, Kodeboyina S, et al. Self-collected oral fluid and nasal swabs demonstrate comparable sensitivity to clinician-collected nasopharyngeal swabs for the detection of SARS-CoV-2. Clin Infect Dis. 2020; Epub ahead of print. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Butler-Laporte G, Lawandi A, Schiller I, Yao M, Dendukuri N, McDonald EG, et al. Comparison of saliva and nasopharyngeal swab nucleic acid amplification testing for detection of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:353–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bastos ML, Perlman-Arrow S, Menzies D, Campbell JR. The sensitivity and costs of testing for SARS-CoV-2 infection with saliva versus nasopharyngeal swabs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:501–10. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Migueres M, Mengelle C, Dimeglio C, Didier A, Alvarez M, Delobel P, et al. Saliva sampling for diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infections in symptomatic patients and asymptomatic carriers. J Clin Virol. 2020;130:

104580 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Tan SY, Tey HL, Lim ETH, Toh ST, Chan YH, Tan PT, et al. The accuracy of healthcare worker versus self collected (2-in-1) Oropharyngeal and Bilateral Mid-Turbinate (OPMT) swabs and saliva samples for SARS-CoV-2. PLoS One. 2020;15:

e0244417 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Landry ML, Criscuolo J, Peaper DR. Challenges in use of saliva for detection of SARS CoV-2 RNA in symptomatic outpatients. J Clin Virol. 2020;130:

104567 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Van Vinh Chau N, Lam VT, Dung NT, Yen LM, Minh NNQ, Hung LM, et al.; Oxford University Clinical Research Unit COVID-19 Research Group. The natural history and transmission potential of asymptomatic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2679–87. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Williams E, Bond K, Zhang B, Putland M, Williamson DA. Saliva as a noninvasive specimen for detection of SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e00776–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Salvatore PP, Dawson P, Wadhwa A, Rabold EM, Buono S, Dietrich EA, et al. Epidemiological correlates of polymerase chain reaction cycle threshold values in the detection of SARS-CoV-2. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;72:e761–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Zange S, Müller MA, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. [Erratum in: Nature. 2020;588:E35]. Nature. 2020;581:465–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Food and Drug Administration. Individual EUAs for molecular diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2. 2021 [cited 2021 Feb 2]. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices/vitro-diagnostics-euas#individual-molecular

1Members are listed at the end of this article.

Page created: June 10, 2021

Page updated: July 18, 2021

Page reviewed: July 18, 2021

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.