Volume 28, Number 6—June 2022

Research

Risk Factors for SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Illness in Cats and Dogs1

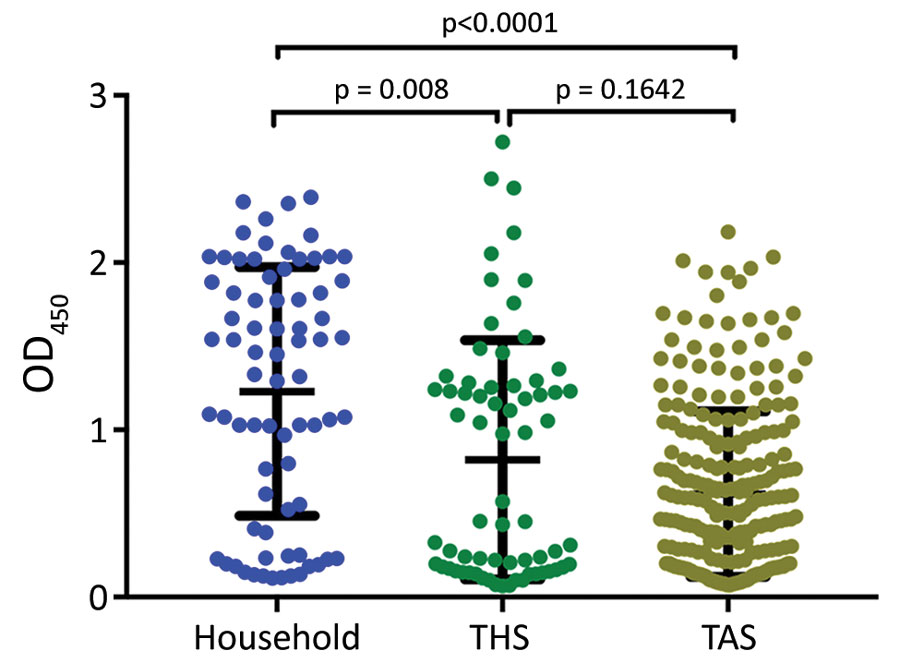

Figure 2

Figure 2. Mean serum SARS-CoV-2 spike protein IgG as measured by ELISA for samples from household cats, from cats in a shelter (THS), and from cats brought to a spay/neuter clinic for care (TAS), Ontario, Canada. The mean and SD are indicated. Differences were significant for household vs. shelter cats and household vs. clinic cats, but not for shelter vs. clinic cats. OD450, optical density at 450 nm; THS, Toronto Humane Society; TAS, Toronto Animal Services.

1Preliminary results from this study were presented at the 30th (September 23–25, 2020) and 31st (July 9–12, 2021) European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.

Page created: April 28, 2022

Page updated: May 22, 2022

Page reviewed: May 22, 2022

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.