Volume 28, Number 9—September 2022

Dispatch

International Spread of Multidrug-Resistant Rhodococcus equi

Figure 1

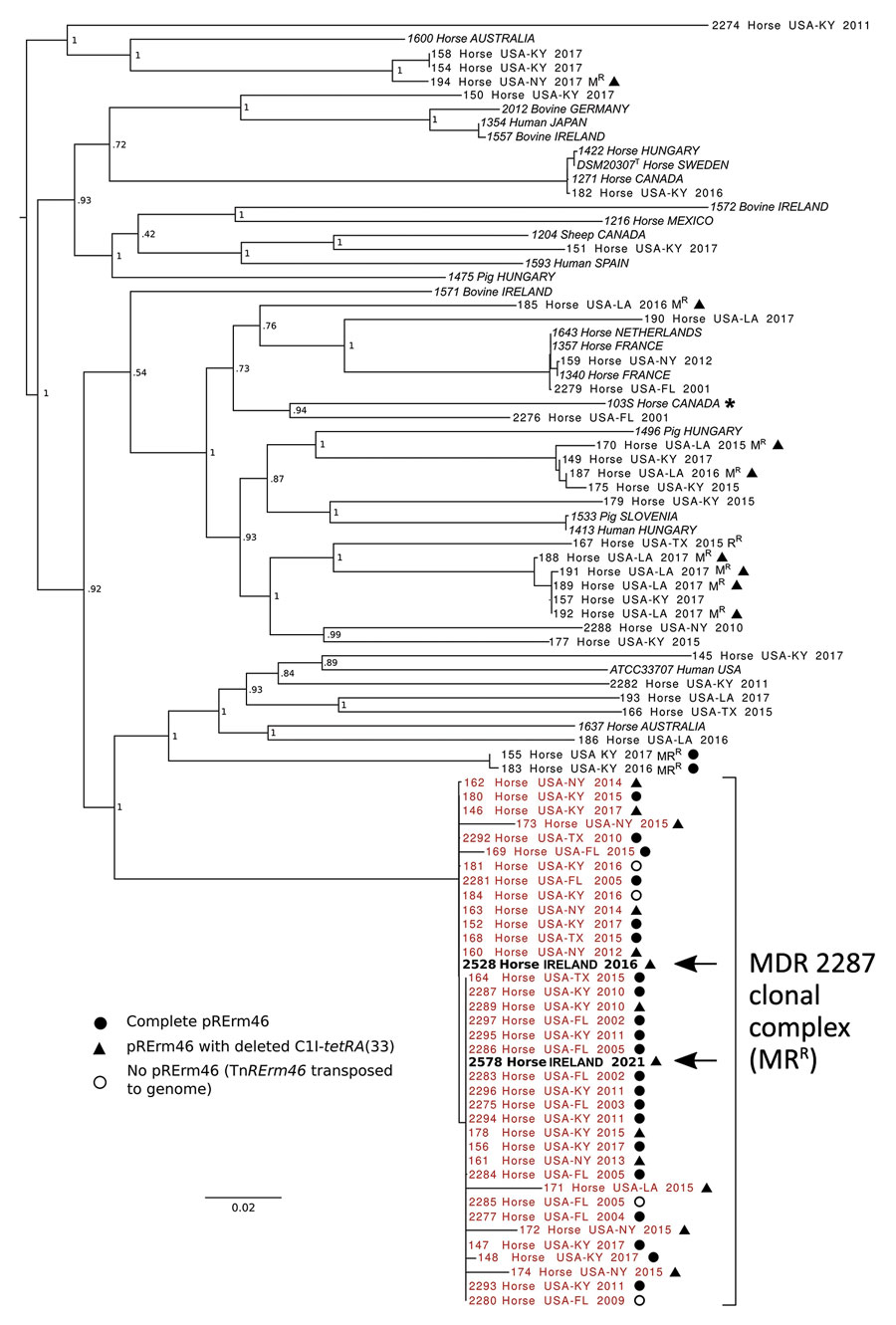

Figure 1. Whole-genome phylogenetic analysis of Rhodococcus equi and its multidrug-resistant 2287 clone. Asterisk indicates strain 103S used as reference genome (GenBank accession no. FN563149). For analysis we used 92 R. equi genome sequences including 68 macrolide-resistant and -susceptible equine isolates from the United States and 22 global strains from a previously reported R. equi diversity set (14) (italics). Macrolide-resistant isolates include 36 members of the MDR-RE 2287 clonal complex (red text) as well as isolates representing spillages of the pRErm46 plasmid to other R. equi genotypes (8,10). Arrows indicate the 2 MDR-RE 2287 isolates from Ireland. Labels indicate geographic origin, year of isolation, and resistance phenotype when applicable (MRR, macrolide and rifampin resistance; MR, macrolide resistance; RR, rifampin resistance). Symbols indicate pRErm46 carriage in macrolide-resistant isolates, described in the key; open circles indicate MDR-RE isolates where pRErm46 has been lost after transposition of the TnRErm46 element to the host genome (8). Numbers at nodes indicate bootstrap values for 1,000 replicates. Tree was drawn with FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree).

References

- Prescott JF. Rhodococcus equi: an animal and human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:20–34. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yamshchikov AV, Schuetz A, Lyon GM. Rhodococcus equi infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:350–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vázquez-Boland JA, Meijer WG. The pathogenic actinobacterium Rhodococcus equi: what’s in a name? Mol Microbiol. 2019;112:1–15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Muscatello G, Leadon DP, Klayt M, Ocampo-Sosa A, Lewis DA, Fogarty U, et al. Rhodococcus equi infection in foals: the science of ‘rattles’. Equine Vet J. 2007;39:470–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Giguère S. Treatment of infections caused by Rhodococcus equi. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2017;33:67–85. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Burton AJ, Giguère S, Sturgill TL, Berghaus LJ, Slovis NM, Whitman JL, et al. Macrolide- and rifampin-resistant Rhodococcus equi on a horse breeding farm, Kentucky, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:282–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Anastasi E, Giguère S, Berghaus LJ, Hondalus MK, Willingham-Lane JM, MacArthur I, et al. Novel transferable erm(46) determinant responsible for emerging macrolide resistance in Rhodococcus equi. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:3184–90.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Álvarez-Narváez S, Giguère S, Anastasi E, Hearn J, Scortti M, Vázquez-Boland JA. Clonal confinement of a highly mobile resistance element driven by combination therapy in Rhodococcus equi. MBio. 2019;10:e02260–19. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Erol E, Scortti M, Fortner J, Patel M, Vázquez-Boland JA. Antimicrobial resistance spectrum conferred by pRErm46 of emerging macrolide (multidrug)-resistant Rhodococcus equi. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59:

e0114921 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Álvarez-Narváez S, Giguère S, Cohen N, Slovis N, Vázquez-Boland JA. Spread of multidrug-resistant Rhodococcus equi, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:529–37. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19:455–77. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Treangen TJ, Ondov BD, Koren S, Phillippy AM. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 2014;15:524. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Anastasi E, MacArthur I, Scortti M, Alvarez S, Giguère S, Vázquez-Boland JA. Pangenome and phylogenomic analysis of the pathogenic actinobacterium Rhodococcus equi. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8:3140–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Baker S, Thomson N, Weill FX, Holt KE. Genomic insights into the emergence and spread of antimicrobial-resistant bacterial pathogens. Science. 2018;360:733–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar