Volume 29, Number 10—October 2023

Research Letter

Plasmodium knowlesi Infection in Traveler Returning to Canada from the Philippines, 2023

Abstract

A 55-year-old man sought treatment for an uncomplicated febrile illness after returning to Canada from the Philippines. A suspected diagnosis of Plasmodium knowlesi infection was confirmed by PCR, and treatment with atovaquone/proguanil brought successful recovery. We review the evolving epidemiology of P. knowlesi malaria in the Philippines, specifically within Palawan Island.

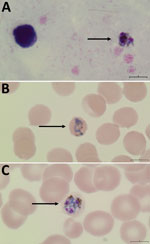

In February 2023, a 55-year-old man sought care at the emergency department of Vancouver General Hospital, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, for daily fevers, headache, and abdominal pain 5 days after returning from a 3-week trip to the Philippines. He stayed mostly in Manila but spent 4 days on Palawan Island in the western Philippines 4 days before his return to Canada; he had not taken malaria chemoprophylaxis. Bloodwork was notable for platelet nadir of 48 × 109/L (reference range 150–450 × 109/L), alanine transaminase of 329 U/L (reference range 10–55 U/L), and alkaline phosphatase of 177 U/L (reference range 30–135 U/L). Results of abdominal computed tomography were unremarkable and of a single-target Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 rapid diagnostic test were negative. Peripheral blood thin smear demonstrated variable intraerythrocytic parasite morphology, including band-like forms suggestive of P. malariae (<0.1% parasitemia) (Figure, panels A–C). Loop-mediated isothermal amplification testing was positive for Plasmodium spp. Given absence of criteria for severe malaria, he was discharged with a 3-day course of atovaquone/proguanil (250 mg/100 mg, 4×/d).

We suspected a diagnosis of P. knowlesi, given the patient’s travel history and blood smear morphology, and subsequently confirmed the infection via species-specific laboratory-developed PCR. Amplicon sequencing on a 118-bp sequence also confirmed P. knowlesi identification. The patient was afebrile at follow-up 4 days after drug therapy, with resolution of thrombocytopenia and symptoms.

P. knowlesi malaria cases within the Philippines have been concentrated in Cebu Province and, as in this case, Palawan Island (Appendix Figure) (1–4). Although P. knowlesi is primarily a simian malaria infecting nonhuman primate hosts, there has been clear transmission evidence across Southeast Asia since the large 2004 Malaysian outbreak in Sabah (5).

Palawan Island contains a diverse landscape of beaches, karst, and mangrove forests, including its well-known Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park. The island provides an ideal feeding and breeding ground for ≈500 long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis), the only monkey species naturally found in the Philippines and natural host reservoirs for P. knowlesi (6). Given the close proximity of the island’s diverse habitats to human settlements and recreation areas, constant contact occurs between forest mosquito vectors, macaque hosts, and, potentially, human hosts (6). The first 5 confirmed local cases within Palawan were documented in 2005 (1); since 2008, only 2 P. knowlesi malaria cases have been documented in North America, both in travelers with implicated exposure from Palawan (Table) (2,7). According to the Philippines Research Institute of Tropical Medicine, >30 P. knowlesi cases have been documented, <5 in tourists traveling to Palawan (Philippines Research Institute of Tropical Medicine, pers. comm., email, 2023 Mar 1). However, the true burden is likely underestimated, given the lack of routine molecular testing for species confirmation in the Philippines. Because early ring-form trophozoites of P. knowlesi can resemble P. falciparum and developing band-like trophozoites can resemble P. malariae (1), molecular species confirmation is a highlighted need in areas at risk for P. knowlesi.

The 24-hour P. knowlesi erythrocytic cycle is shortest among Plasmodium spp., which may contribute to rapid development of high parasitemia (5), although this case showed ultra-low parasitemia. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that uncomplicated P. knowlesi malaria infections acquired in P. vivax chloroquine-susceptible regions be treated with an oral artemisinin-combination therapy or chloroquine; cases acquired in P. vivax chloroquine-resistant regions should be treated with locally available artemisinin-combination therapy (8). Despite limited data regarding antimalarial resistance among P. knowlesi parasites, this strategy ensures adequate treatment of undiagnosed mixed infections and simplification of uncomplicated malaria treatment. Intravenous artesunate remains first-line treatment for severe P. knowlesi malaria. As in this case, atovaquone/proguanil is also considered reasonable empiric treatment.

The Philippines successfully established 0 indigenous cases of malaria across 78 of 81 provinces in 2019; ≈97% of indigenous cases were P. falciparum or P. vivax. Recent serologic work showed that 1.1% of personsin Palawan tested positive for P. knowlesi–specific PkSERA3ag1 antibody (9). Current control strategies for human-species malaria (e.g., insecticide-treated nets, indoor spraying) have limited impact on monkey reservoirs and on forest-dwelling P. knowlesi vectors, given limited evidence of indoor biting (9,10). Palawan and Sabah surveillance data identified that most biting by Anopheles balabacensis mosquitoes occurred during 6–10 pm, when many rural residents are still outdoors. Although Palawan reports more sporadic cases than does Malaysia, increased encroachment into deforested areas and close proximity (<100 km) to endemic Sabah raises concern of P. knowlesi becoming a predominant species in future years. Ongoing investigations into mosquito behavior implicated with cross-species transmission will help inform appropriate control strategies for P. knowlesi and other simian species (9).

In summary, P. knowlesi malaria should be considered in persons with febrile illness who have traveled to the Philippines (especially Cebu Province and Palawan Island). Because of overlapping microscopy features with P. falciparum and P. malariae, molecular confirmation is required to enable early diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Despite gains in control of P. falciparum and P. vivax infection in Southeast Asia, the zoonotic nature of P. knowlesi and rise in cases highlight the need for tailored prevention and control strategies.

Dr. Lo is a medical microbiology resident physician at the University of British Columbia. His research interests include tropical infectious diseases, parasitology, and Clostridioides difficile infection prevention.

Acknowledgment

We thank the parasitology staff and microbiologists of the British Columbia Centre of Disease and Control Public Health Laboratory for their contribution toward testing and workup of patient specimen and John Tyson for confirmatory sequencing. We also thank the Philippines Research Institute of Tropical Medicine for providing their expert opinion regarding local P. knowlesi epidemiologic trends.

References

- Luchavez J, Espino F, Curameng P, Espina R, Bell D, Chiodini P, et al. Human infections with Plasmodium knowlesi, the Philippines. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:811–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Simian malaria in a U.S. traveler—New York, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:229–32.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- De Canale E, Sgarabotto D, Marini G, Menegotto N, Masiero S, Akkouche W, et al. Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in a traveller returning from the Philippines to Italy, 2016. New Microbiol. 2017;40:291–4.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Takaya S, Kutsuna S, Suzuki T, Komaki-Yasuda K, Kano S, Ohmagari N. Case report: Plasmodium knowlesi infection with rhabdomyolysis in a Japanese traveler to Palawan, the Philippines. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;99:967–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Singh B, Daneshvar C. Human infections and detection of Plasmodium knowlesi. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:165–84. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gamalo LE, Dimalibot J, Kadir KA, Singh B, Paller VG. Plasmodium knowlesi and other malaria parasites in long-tailed macaques from the Philippines. Malar J. 2019;18:147. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mace KE, Lucchi NW, Tan KR. Malaria Surveillance - United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2022;71(No. SS-8):1–35. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for malaria. Report no.: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Geneva: The Organization; 2023.

- Malijan RPB, Mechan F, Braganza JC Jr, Valle KMR, Salazar FV, Torno MM, et al. The seasonal dynamics and biting behavior of potential Anopheles vectors of Plasmodium knowlesi in Palawan, Philippines. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14:357. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Thang ND, Erhart A, Speybroeck N, Xa NX, Thanh NN, Ky PV, et al. Long-Lasting Insecticidal Hammocks for controlling forest malaria: a community-based trial in a rural area of central Vietnam. PLoS One. 2009;4:

e7369 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Table

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: September 18, 2023

Table of Contents – Volume 29, Number 10—October 2023

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Catherine A. Hogan, British Columbia Centre of Disease and Control, 655 W 12th Ave, Rm 2054, Vancouver, BC V6R 2M7, Canada

Top