Volume 30, Number 2—February 2024

Research Letter

Model for Interpreting Discordant SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostic Test Results

Figure

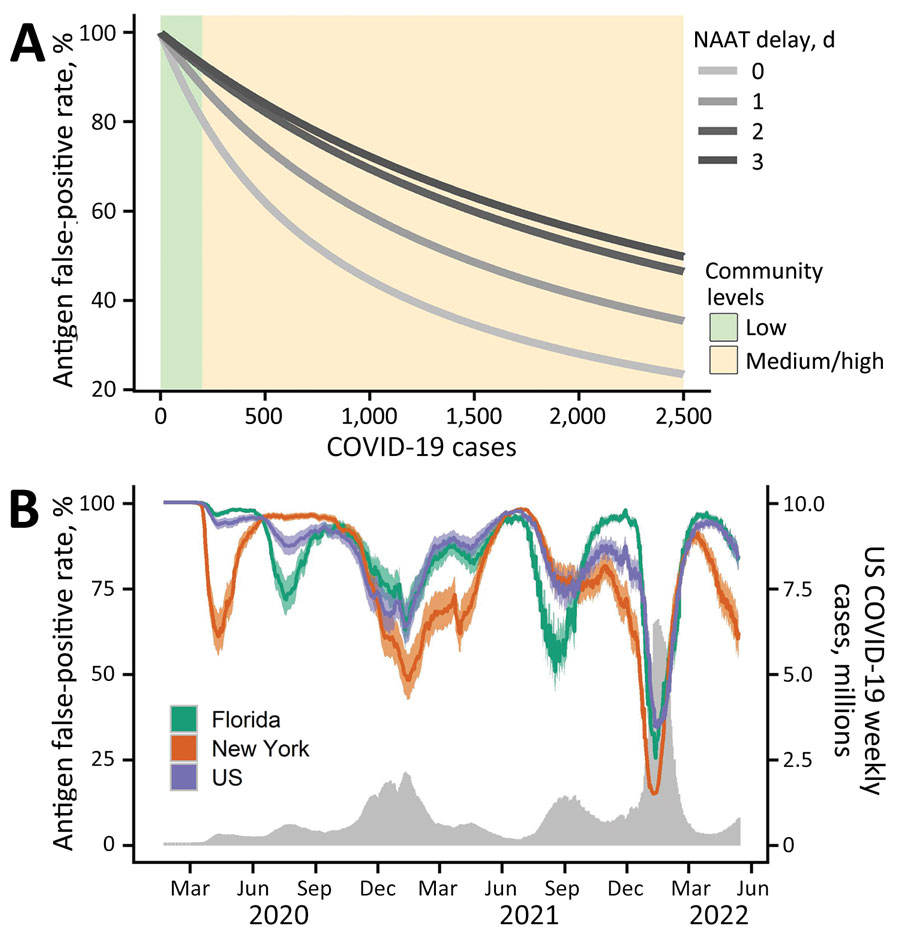

Figure. Estimated probability that a positive RAT result is erroneous given a subsequent negative NAAT in a model for interpreting discordant SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic test results. A) Estimated RAT false-positive percentages for levels of community transmission ranging from 0–2,500 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population. Green and yellow shading correspond to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention threshold for low and medium or high community levels (8). Line color corresponds to different numbers of days between the initial RAT and confirmatory NAAT, ranging from same day (lightest gray) to 3 days later (black). B) Estimated RAT false-positive percentages for the United States (purple), Florida (green), and New York (orange) during March 2020–May 2022, assuming the NAAT is administered 1 day after the RAT and that 1 in 4 cases were reported. Shading reflects uncertainty in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated COVID-19 infection underreported, ranging from 1 in 3 to 1 in 5. The gray time series along the bottom indicates the daily 7-day sum of reported COVID-19 cases in the United States. NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; RAT, rapid antigen test.

References

- Wong G, Liu W, Liu Y, Zhou B, Bi Y, Gao GF. MERS, SARS, and Ebola: the role of super-spreaders in infectious disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;18:398–401. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kucirka LM, Lauer SA, Laeyendecker O, Boon D, Lessler J. Variation in false-negative rate of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction–based SARS-CoV-2 tests by time since exposure. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:262–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yang S, Rothman RE. PCR-based diagnostics for infectious diseases: uses, limitations, and future applications in acute-care settings. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:337–48. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schuit E, Veldhuijzen IK, Venekamp RP, van den Bijllaardt W, Pas SD, Lodder EB, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of rapid antigen tests in asymptomatic and presymptomatic close contacts of individuals with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2021;374:n1676. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Filgueiras PS, Corsini CA, Almeida NBF, Assis JV, Pedrosa MLC, de Oliveira AK, et al. COVID-19 rapid antigen test at hospital admission associated to the knowledge of individual risk factors allow overcoming the difficulty of managing suspected patients in hospitals. Fortune J Health Sci. 2022;5:211–31. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Gans JS, Goldfarb A, Agrawal AK, Sennik S, Stein J, Rosella L. False-positive results in rapid antigen tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2022;327:485–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kanji JN, Proctor DT, Stokes W, Berenger BM, Silvius J, Tipples G, et al. Multicenter postimplementation assessment of the positive predictive value of SARS-CoV-2 antigen-based point-of-care tests used for screening of asymptomatic continuing care staff. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59:

e0141121 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), Division of Viral Diseases. Science brief: indicators for monitoring COVID-19 community levels and making public health recommendations. In: CDC COVID-19 science briefs. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated COVID-19 burden [cited 2022 May 25]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/burden.html

- Osterman A, Badell I, Basara E, Stern M, Kriesel F, Eletreby M, et al. Impaired detection of omicron by SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen tests. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl). 2022;211:105–17. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

1These first authors contributed equally to this article.