Volume 31, Number 6—June 2025

Dispatch

Skin Infections Caused by Panton-Valentine Leukocidin and Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in Child, Japan

Abstract

We describe a pediatric case of recurrent skin infections caused by a Panton-Valentine leukocidin and exfoliative toxin E double-positive methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus clonal complex 188 clone. Most of the patient’s family members were infected with the same strain, and intrafamilial transmission was strongly suspected. Decolonization procedures were not effective.

Recurrent skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) caused by Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL)–positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) have been reported worldwide (1,2). Recurrence may be attributed to intrafamilial transmission; in such cases, decolonization by nasal mupirocin ointment and topical skin application of 4% chlorhexidine are treatments for family members (3). Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) strains that possess virulence factors similar to those of MRSA have been reported (4,5); however, the clinical significance of such bacterial strains and the efficacy of decolonization are still unclear. We report a case of a child in Japan with recurrent SSTIs caused by PVL and exfoliative toxin E (ETE) double-positive MSSA refractory to decolonization, with evidence of intrafamilial transmission.

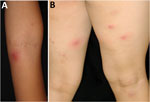

A 7-year-old girl with atopic dermatitis was referred to the National Center for Child Health and Development (Tokyo, Japan) for impetigo and recurrent multiple furuncles (furunculosis) (Figure 1). The child had no history of serious infections and no suspected immunodeficiencies. We instructed the patient to maintain skin cleanliness by showering and using moisturizers and to repeatedly treat with oral antimicrobial agents when furuncles manifested. However, the skin lesions relapsed 2–4 weeks after discontinuing the antimicrobial therapy. Culture of the pus from a furuncle identified MSSA (strain name JH62PP1) (Appendix Table).

The patient’s father, older brother (12 years of age), and younger brother (3 years of age) also had similar skin lesions; we suspected intrafamilial infection of MSSA. In addition to lifestyle guidance (hand hygiene; keeping fingernails short; changing underwear, towels, and sleepwear each day; washing sheets and pillowcases weekly; washing the body with soap daily; and avoiding sharing personal items), all family members underwent decolonization using mupirocin ointment (applied to each nostril 3×/d for 3 days) and 4% chlorhexidine (applied to all skin areas below the neck 3×/wk for 4 weeks). Although the time interval between relapse of skin lesions increased temporarily, the frequency returned to the same level ≈4 months after the first decolonization (Figure 2).

We then attempted decolonization for the patient and each family member with a bleach bath in water containing 0.005% hypochlorous acid as approved by the institutional ethics committee (NCCHD-1912). We instructed the patient and family to first wash their bodies with soap, then soak in the bathtub for 5–10 minutes, and finally rinse thoroughly in the shower. They performed the procedure twice a week. However, recurrences occurred within ≈2 weeks, indicating that the bath was not effective.

We assessed the patient’s immune condition by blood tests, including a complete blood count with differential, immunoglobulin and complement levels, lymphocyte proliferation assay, superoxide production, and flow cytometry. The results of those tests were within reference ranges; we considered known primary immunodeficiencies, including chronic granulomatous disease and hyper-IgE syndrome, unlikely. Thereafter, we abandoned attempts at decolonization and gave the patient oral antimicrobial medication when a skin lesion formed. The frequency of skin lesions improved when the patient was 10 years of age; we observed no relapses after the patient turned 11, with no additional interventions. Outpatient follow-up ended.

In this case, we strongly suspected familial transmission of S. aureus. Therefore, we conducted a phylogenetic analysis using whole-genome sequencing on a total of 7 MSSA strains: 2 strains (JH62PP1 and JH62PP2) isolated from swab specimens of the patient’s pus at the initial and follow-up visits and 5 strains (JH62PN, JH62F, JH62M, JH62B1, and JH62B2) isolated from nasal swab specimens of the patient and 4 other family members before decolonization treatment. We performed purification of genomic DNA, preparation of sequencing libraries, whole-genome sequencing, and core-genome–based phylogenetic analyses in this study as previously described (6). We deposited raw read sequences obtained in this study in GenBank/DDBJ/EMBL (BioProject no. PRJDB19081).

MLST analysis revealed that the JH62PP1 and JH62PN strains isolated from the patient’s pus and nasal swab specimens at the initial visit, as well as those (JH62F, JH62M, and JH62B1) from nasal swab specimens of the father, mother, and older brother, were identified as MSSA sequence type (ST) 2233 (Appendix Figure 1). ST2233 belongs to clonal complex (CC) 188, as determined by eBURST analysis of PHYLoViZ version 2.0 web tool (https://www.phyloviz.net). JH62PP2, isolated from the patient’s pus at the follow-up visit, belonged to ST1, and JH62B2, isolated from the younger brother’s nasal swab, ST188; their STs were distinct from ST2233, which was the ST of the suspected strain of household transmission. In the case of S. aureus, the single-nucleotide polymorphism cutoff value for excluding patient-to-patient transmission in an outbreak setting is considered to be <15 within the previous 6 months (7). Therefore, all ST2233 isolates from the 4 family members were found to be very closely related, confirming that the causative clone was transmitted within the family.

We also investigated the virulence, antimicrobial-resistance, and disinfectant-resistance genes by whole-genome sequencing analysis (Table). Five ST2233 isolates possessed multiple virulence genes: Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes lukS-PV and lukF-PV; staphylococcal enterotoxin genes seg, seh, sei, sem, sen, seo, ses, and seu; exfoliative toxin gene ete; and some antimicrobial-resistance genes, including β-lactam resistance gene blaZ and quinolone resistance–determining region mutations GrlA S80Y and GyrA S84L. However, we did not detect the mupirocin-resistance gene mup or any qac homologs, such as qacA, qacB, qacE, qacG, and qacH, which are known as disinfectant-resistance genes and known to reduce efficacy (8,9). We also investigated biofilm formation, which is associated with bacterial colonization and drug resistance. However, the biofilm-forming ability of these ST2233 strains was only slightly higher than that of the negative control FK300 (p<0.05) and not particularly strong (Appendix Figure 2).

ETE is a recently identified toxin that specifically degrades desmoglein-1 in the epidermis of many mammal species, including humans (10). A PVL and ETE double-positive strain is very rare; only 1 case has been reported, from necrotizing fasciitis (11). We have not found other reports of PVL and ETE double-positive S. aureus belonging to CC188, the most frequently isolated clone from healthy adult skin in Japan.

SSTIs caused by S. aureus are known to recur. A large multicenter cohort study of 959 staphylococcal SSTI cases revealed that 16.4%–19.0% of patients experienced >1 recurrence within a 12-month follow-up period (1). Intrafamilial transmission of S. aureus in patients with SSTIs is also known; Rodriguez et al. reported that among 163 pediatric patients with community-associated S. aureus SSTIs, intrafamilial strain relationships were observed in 105 (64%) families (12). Decolonization is occasionally attempted for all family members of patients with relapsing staphylococcal SSTIs; well-known decolonization techniques are nasal decolonization by mupirocin ointment and topical body decolonization by chlorhexidine (3) and sometimes bleach baths, in which the patient bathes in a bathtub filled with diluted hypochlorous acid water (13). Although we applied all 3 techniques to our patient and her family members, they were ineffective. Detailed strain analysis showed that the strains did not harbor resistance genes to mupirocin or disinfectants, and resistance to them was not the cause of their insufficient efficacy. Further strategies to control relapsing staphylococcal SSTI are required.

In summary, we encountered a child with relapsing SSTI caused by a PVL and ETE double-positive MSSA ST2233 strain that was refractory to decolonization procedures. Further investigation will reveal the clinical significance of the ST2233 strain and effective techniques for decolonization. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of disinfectant resistance in SSTIs caused by MSSA infections.

Dr. Shoji is a staff physician in the Division of Infectious Disease at the National Center for Child Health and Development, Japan. His research interests focus on pediatric pharmacology and infections in immunocompromised children.

Acknowledgments

We obtained written permission for publication from the patient’s parents.

This study was supported by a grant (no. NCCHD 30E-1) from the National Center for Child Health and Development to I.M. and partly supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development under the Research Program on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases (grant no. JP21fk0108604 to M.S.).

We used an artificial intelligence tool for grammatical correction of the manuscript.

All authors declare that they do not have any potential, perceived, or real conflicts of interest relevant to this study. All authors meet ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Author contributions: J.H., C.A., and K.M. assisted with and provided advice on experiments regarding the genomic analysis of S. aureus. K.S. and I.M. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and J.H., S.K., C.A., K.M., and M.S. performed the analysis of the MSSA strain. T.I. and T.K. performed the immunologic assessment of the patient. T.I., T.K., K.Y., M.T., and K.U. revised the manuscript.

References

- Vella V, Galgani I, Polito L, Arora AK, Creech CB, David MZ, et al. Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infection recurrence rates in outpatients: a retrospective database study at 3 US medical centers. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e1045–53. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McNeil JC, Fritz SA. Prevention strategies for recurrent community-associated Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2019;21:12. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, et al.; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e18–55. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bourigault C, Corvec S, Brulet V, Robert PY, Mounoury O, Goubin C, et al. Outbreak of skin infections due to Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in a French prison in 2010–2011. PLoS Curr. 2014;6:ecurrents.outbreaks.e4df88f057fc49e2560a235e0f8f9fea

- Gopal Rao G, Batura R, Nicholl R, Coogan F, Patel B, Bassett P, et al. Outbreak report of investigation and control of an outbreak of Panton-Valentine Leukocidin-positive methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (PVL-MSSA) infection in neonates and mothers. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:178. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Inagawa T, Hisatsune J, Kutsuno S, Iwao Y, Koba Y, Kashiyama S, et al. Genomic characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from patients admitted to intensive care units of a tertiary care hospital: epidemiological risk of nasal carriage of virulent clone during admission. Microbiol Spectr. 2024;12:

e0295023 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Coll F, Raven KE, Knight GM, Blane B, Harrison EM, Leek D, et al. Definition of a genetic relatedness cutoff to exclude recent transmission of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a genomic epidemiology analysis. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1:e328–35. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hetem DJ, Bonten MJ. Clinical relevance of mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Infect. 2013;85:249–56. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Furi L, Ciusa ML, Knight D, Di Lorenzo V, Tocci N, Cirasola D, et al.; BIOHYPO Consortium. Evaluation of reduced susceptibility to quaternary ammonium compounds and bisbiguanides in clinical isolates and laboratory-generated mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3488–97. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Imanishi I, Nicolas A, Caetano AB, Castro TLP, Tartaglia NR, Mariutti R, et al. Exfoliative toxin E, a new Staphylococcus aureus virulence factor with host-specific activity. Sci Rep. 2019;9:16336. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sabat AJ, Wouthuyzen-Bakker M, Rondags A, Hughes L, Akkerboom V, Koutsopetra O, et al. Case Report: Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus positive for a new sequence variant of exfoliative toxin E. Front Genet. 2022;13:

964358 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Rodriguez M, Hogan PG, Burnham CA, Fritz SA. Molecular epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus in households of children with community-associated S aureus skin and soft tissue infections. J Pediatr. 2014;164:105–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hogan PG, Parrish KL, Mork RL, Boyle MG, Muenks CE, Thompson RM, et al. HOME2 study: household versus personalized decolonization in households of children with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infection—a randomized clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e4568–77. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Table

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: May 21, 2025

Table of Contents – Volume 31, Number 6—June 2025

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Kensuke Shoji, National Center for Child Health and Development, 2-10-1 Okura, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo 157-8535, Japan

Top