Volume 5, Number 2—April 1999

Synopsis

Enteropathogenic E. coli, Salmonella, and Shigella: Masters of Host Cell Cytoskeletal Exploitation

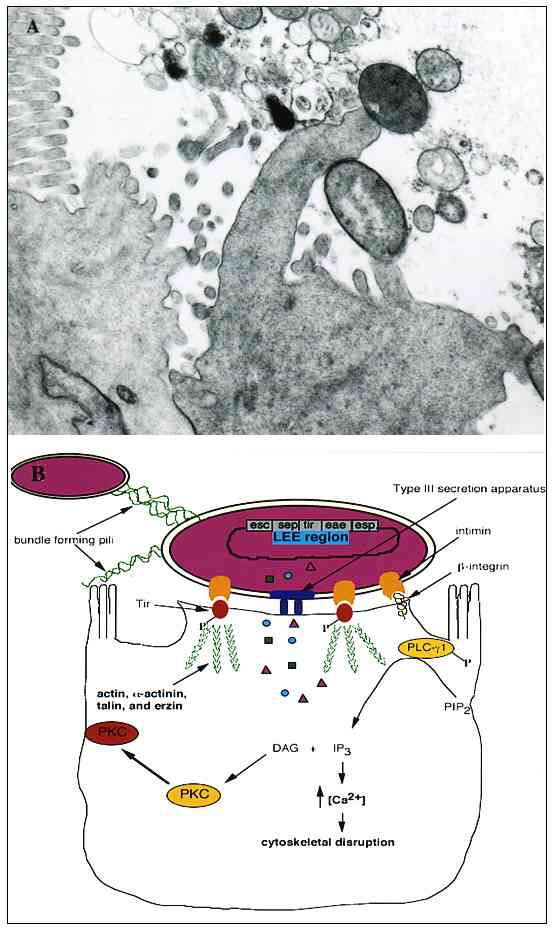

Figure 1

Figure 1. A. Transmission electron micrograph of an A/E lesion formed by rabbit enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) infecting rabbit intestinal epithelial cells (micrograph provided by Dr. Ursula Heczko, Biotechnology Laboratory, University of British Columbia). B. Effects of EPEC infection on host intestinal epithelial cells. EPEC initially adheres to the host cell by its bundle-forming pili, which also mediate bacterial aggregation. Following initial attachment, EPEC secretes several virulence factors by a type III-secretion system. Signal transduction events occur within the host, including activation of phospholipase C (PLC) and protein kinase C (PKC), inositol triphosphate (IP3) fluxes, and Ca2+ release from internal stores. The bacterium intimately adheres to the cell by secreting its own receptor, Tir, into the host and binding to it with its outer membrane ligand, intimin. Intimin can also bind ß1-integrins. Several cytoskeletal proteins are recruited to the site of EPEC attachment, including actin, α-actinin, talin, and ezrin. Cytoskeletal rearrangements occur following Tir-intimin binding, resulting in the formation of a pedestal-like structure upon which the pathogen resides.