Volume 5, Number 4—August 1999

THEME ISSUE

Bioterrorism

Historical Review

Historical Trends Related to Bioterrorism: An Empirical Analysis

Since the Japanese doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo released sarin nerve gas on the Tokyo subway in March 1995, killing 12 people, terrorist incidents and hoaxes involving toxic or infectious agents have been on the rise. Before the late 1990s, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) typically investigated a dozen cases per year involving the acquisition or use of chemical, biological, radiologic, or nuclear materials; however, FBI opened 74 such investigations in 1997 and 181 in 1998 (1). Although 80% of these incidents have been hoaxes, some were unsuccessful attacks (2).

The vulnerability of civilian populations to chemical, biological, radiologic, or nuclear terrorism has been widely discussed, but information on historical cases is anecdotal and often inaccurate (3). Without a realistic threat assessment based on solid empirical data, government policymakers lack the knowledge they need to design prudent and cost-effective programs for preventing or mitigating future incidents.

Responding to this knowledge gap, the Chemical and Biological Weapons Nonproliferation Project at the Monterey Institute's Center for Nonproliferation Studies has compiled an open-source database of all publicly known cases from 1900 to the present in which domestic or international criminals or terrorists sought to acquire or use chemical, biological, radiologic, or nuclear materials. As of January 31, 1999, the database contained 415 incidents, both domestic and international. Each entry draws on multiple sources and includes a detailed description of the event and a list of citations.

The project has conducted a preliminary analysis of the data to discern patterns over time in the frequency of such incidents, the underlying motives, and the choice of agent and target. The ultimate goal is to identify which types of individuals or groups are most likely to acquire and use toxic or infectious materials and for what purposes.

Since the Monterey Database has been compiled from journalistic accounts and other unclassified sources, it may not be comprehensive or fully accurate. Incidents have been recorded only if they came to the attention of law enforcement or the news media, so the database does not include events that were not detected or whose existence remains secret. Despite these limitations, the information in the database indicates trends and patterns of behavior that may assist intelligence and law-enforcement personnel in focusing their monitoring efforts.

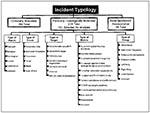

Most of the incidents in the Monterey Database involve chemical or biological agents rather than radiologic or nuclear materials (Figure 1). The cases have been divided into three categories: terrorist events, criminal events, and state-sponsored assassinations. To be classified as a terrorist event, an incident must involve an organization or person that conspires to use violence instrumentally to advance a political, ideologic, or religious goal. Criminal incidents, in contrast, involve extortion, murder, or some other nonpolitical objective. Of the 415 incidents involving chemical, biological, radiologic, or nuclear materials, 151 cases are terrorist events for which information is sufficient to permit cross-case comparison. These incidents have been classified according to type of agent, event, target, motive, and group (Figure 2).

"Type of event" includes the following categories: 1) conspiracy to acquire and use an agent, 2) attempted acquisition, 3) possession, 4) threatened use, 5) actual use, and 6) hoax or prank. Most of the 151 incidents involve threatened or actual use, although rarely with the intent of inflicting mass casualties. Of the 151 terrorist incidents, a subset of 33 involves biological agents (22 alleged biological cases were dropped from the analysis because they lacked key pieces of information). Many of the biological-agent cases are hoaxes.

Since 1985, the number of terrorist incidents involving the threatened or actual use of chemical, biological, radiologic, or nuclear materials has risen sharply; a more modest increase has occurred in efforts to acquire such agents. When criminal and terrorist incidents involving chemical or biological agents are examined, two large peaks become apparent (Figure 3a). The 1995 peak was associated primarily with Aum Shinrikyo and related copycat attacks in Japan; in 1998, incidents of actual use again increased abruptly (Figure 3a).

Hoaxes involving chemical or biological agents have shown two peaks in frequency over the past 30 years (Figure 3b). The 1986 peak in chemical hoaxes was inspired by the second series of Tylenol poisonings, while the dramatic rise in biological hoaxes in 1998 is attributable to the flurry of anthrax threats in the United States. The first wave of anthrax hoaxes followed the well-publicized arrest on February 18, 1998, of Larry Wayne Harris, a microbiologist linked to white-supremacist groups, after he allegedly threatened to release "military-grade anthrax" in Las Vegas (4). Although Harris's anthrax turned out to be a harmless veterinary vaccine strain, sensational media coverage appears to have had the unintended effect of popularizing this agent among potential perpetrators.

The categories of terrorist organizations involved in the acquisition and use of chemical, biological, radiologic, or nuclear materials have changed over time. Omitting incidents involving lone terrorists, recent years have seen a rise in cases involving three types of terrorist organizations: single-issue groups such as those dealing with abortion and animal rights; nationalist and separatist groups such as Chechen rebel organizations, the Kurdistan Workers Party, and the Tamil Tigers of Sri Lanka; and apocalyptic religious cults such as Aum Shinrikyo (although Aum accounts for nearly all the latter cases). No clear pattern is apparent in the types of groups involved in biological incidents, although religious fundamentalism as a motivation has emerged within the past 5 years.

The preferred choice of target has also changed over time. If one examines 135 terrorist incidents for which the target is known, two types of targets have increased in frequency: the general civilian population (with the apparent intent of inflicting indiscriminate casualties) and a symbolic building or organization.

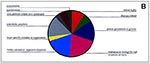

Motivations for the terrorist use of chemical, biological, radiologic, or nuclear materials appear to encompass a wide range of objectives. (For each case, two analysts separately determined the "best fit" to a menu of motivations.) In descending order, the main motivations are: 1) to promote nationalist or separatist objectives; 2) to retaliate or take revenge for a real or perceived injury; 3) to protest government policies; and 4) to defend animal rights (Figure 4). A similar breakdown of motivations is found in the incidents involving biological agents, except for the greater prominence of apocalyptic prophecy (Figure 5). Nearly all the latter cases are linked to Aum Shinrikyo, which may be either an outlier or a trend-setter.

The motivations underlying terrorist incidents with chemical, biological, radiologic, or nuclear materials appear to have shifted over time. The predominant motivation from 1975 to 1989 was to protest government policies. Since 1990, however, the leading motivations have been to further nationalist or separatist objectives and for retaliation or revenge. In 1993, because of Aum Shinrikyo, apocalyptic prophecy also emerged as an important motivation. The prominence of these three motivations becomes even greater when only incidents involving biological agents are examined.

In addition to compiling the incidents database, the project commissioned historical case studies of seven terrorist groups or individuals that acquired or employed biological agents (Table 1). Two of the cases appear to be apocryphal, but the five confirmed cases share a number of characteristics that may be diagnostic of groups and individuals most likely to engage in bioterrorism (Table 2). These characteristics include diffuse objectives, a sense of grandiosity, and a paranoid, conspiratorial, or apocalyptic world view that may lead to "defensive aggression." Such terrorists also lack a domestic political constituency that might restrain them from engaging in indiscriminate violence. Religiously motivated cults such as Aum Shinrikyo and the Rajneeshees are cut off from the outside world and are often guided by a charismatic, all-powerful leader, making them less subject to societal norms. Other factors not listed in the table include a tendency to escalate terrorist violence over time and to use innovative weapons and tactics.

The Monterey Database indicates that incidents involving biological agents have been quite rare, with 66 criminal events and 55 terrorist events over the 40-year period from 1960 to 1999, although the frequency of such incidents (mainly hoaxes) has increased sharply in recent years. The historical record includes few cases in which criminals or terrorists sought to inflict mass casualties with biological agents, and none in which they succeeded. Only eight criminal attacks with biological agents led to casualties, inflicting a total of 29 deaths and 31 injuries. Of the terrorist attacks with biological agents, only one resulted in casualties: the use by the Rajneeshee cult in 1984 of Salmonella Typhimurium bacteria to contaminate restaurant salad bars in The Dalles, Oregon. This event caused 751 cases of food poisoning, none fatal (5).

Incidents of bioterrorism in the Monterey Database are extremely diverse in terms of type of group and motivation. The trend in recent years has been away from left-wing terrorism and toward nationalist-separatist groups and individuals or ad hoc groups bent on revenge. There has also been an apparent rise in incidents perpetrated by violent sects or cults that believe in apocalyptic prophecy.

Even if the motivation to inflict mass casualties exists, however, few terrorist groups possess the scientific-technical resources required for the successful large-scale release of a biological agent. Aum Shinrikyo, which had considerable wealth and scientific expertise, failed in 10 separate attempts to carry out open-air attacks against urban targets with aerosolized anthrax spores or botulinum toxin (6).

In summary, the historical record suggests that future incidents of bioterrorism will probably involve hoaxes and relatively small-scale attacks, such as food contamination. Nevertheless, the diffusion of dual-use technologies relevant to the production of biological and toxin agents, and the potential availability of scientists and engineers formerly employed in sophisticated biological warfare programs such as those of the Soviet Union and South Africa, suggest that the technical barriers to mass-casualty terrorism are eroding.

Dr. Tucker is director of the Chemical and Biological Weapons Nonproliferation Project, Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Monterey Institute of International Studies.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Jason Pate and Diana McCauley for their outstanding work in compiling and analyzing the Monterey Database of chemical, biological, radiologic, and nuclear incidents.

References

- Parker-Tursman J. FBI briefed on district's terror curbs. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 5, 1999.

- Weiner T. Reno says U.S. may stockpile medicine for terrorist attacks. New York Times 1998 Apr 23; Sect. A:12.

- For a revealing account of the inconsistencies and inaccuracies in the secondary literature on CBW terrorism, see Ron Purver, Chemical and biological terrorism: the threat according to the open literature (Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Security Intelligence Service, June 1995).

- Edwards TM. Catching a 48-hour bug. Time. 1998;:56–7.

- Török TJ, Tauxe RV, Wise RP, Livengood JR, Sokolow R, Mauvais S, A large community outbreak of salmonellosis caused by intentional contamination of restaurant salad bars. JAMA. 1997;278:389–95. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- WuDunn S. Miller J, Broad WJ. How Japan germ terror alerted world. New York Times 1998 May 26; Sect A:1 (col 1), A:10 (col 1-5).

Figures

Tables

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 5, Number 4—August 1999

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Jonathan B. Tucker, Chemical and Biological Weapons Nonproliferation Project, Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Monterey Institute of International Studies, 425 Van Buren Street, Monterey, CA 93940, USA; fax: 831-647-6534

Top