Volume 6, Number 5—October 2000

Research

Naturally Occurring Ehrlichia chaffeensis Infection in Coyotes from Oklahoma

Figure

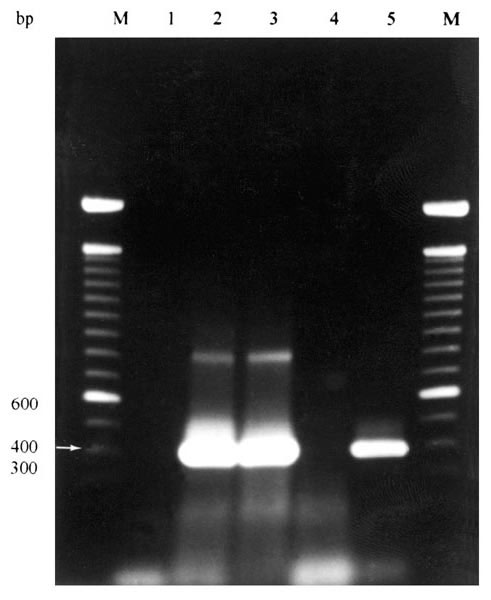

Figure. Agarose gel electrophoresis of results of PCR amplification of Ehrlichia chaffeensis nss rRNA gene from whole blood samples of coyotes numbers 9-11.* Lane 1= negative control (no DNA); Lane 2= coyote 9 (+); Lane 3= coyote 10 (+); Lane 4= coyote 11 (-); Lane 5 = positive control (E. chaffeensis-infected DH82 cells). M = 100-bp DNA ladder (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD).* * Ehrlichia forward primer ECC (5'-AGAACGAACGCTGGCGGCAAGC-3') and Ehrlichia reverse primer ECB (5'-CGTATTACCGCGGCTGCTGGCA-3') amplified all Ehrlichia spp (12,18). These reactions (50 l) contained 10 l of template DNA in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.3), 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 2 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.5 m each primer, and 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). A hot-start PCR was used in which each enzyme was added to reactions after an initial 3-min denaturation step at 94°C. Reactions consisted of 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 65°C for 2 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min. Products of this reaction were used as template with species-specific primer sets for three nested reactions. Primers HE1 (5'-CAATTGCTTATAACCTTTTGGTTATAAAT-3') and HE3 (5'-TATAGGTACCGTCATTATCTTCCCTAT-3') (17) were used for E. chaffeensis-specific amplifications. Primers ECAN5 (5'-CAATTATTTATAGCCTCTGGCTATAGGA-3') (12,13) and HE3 were used for E. canis-specific amplifications, and primers EE5 (5'-(CAATTCCTAAATAGTCTCTGACTATTTAG-3') (this study) and HE3 were used for E. ewingii-specific amplifications. Reactions (50 l) contained 10 l of the reaction product with ECC and ECB primers as template, and the remaining reaction components as above. A hot-start PCR was used in which the enzyme was added to reactions after an initial 3-min denaturation step at 94°C. Reactions with species-specific primers were in two stages. The first consisted of three cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55oC for 2 min, and extension at 72°C for 1.5 min. The second consisted of 37 cycles of denaturation at 92°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 2 min, and extension at 72°C for 1.5 min. Distilled, deionized water served as a negative control. Positive control DNA samples were purified from E. chaffeensis-infected DH82 cells, blood from a dog experimentally infected with E. canis, and diluted general primer PCR reactions of synovial fluid from a dog experimentally infected with E. ewingii. To prevent contamination of samples, DNA purification, PCR master mix assembly, and amplifications were performed in separate rooms. Positive displacement pipetters and aerosol-free pipette tips were also used as further precautions.

References

- Eng TR, Harkess JR, Fishbein DB, Dawson JE, Greene CN, Rredus MA, Epidemiologic, clinical and laboratory findings of human ehrlichiosis in the United States,1988. JAMA. 1990;264:2251–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dawson JE, Childs JE, Biggie KL, Moore C, Stallknecht DE, Shaddock J, White-tailed deer as a potential reservoir for Ehrlichia chaffeensis, the etiologic agent of human ehrlichiosis. J Wildl Dis. 1994;30:162–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ewing SA, Dawson JE, Kocan AA, Barker RW, Warner CK, Panciera RJ, Experimental transmission of Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Rickettsiales: Ehrlichieae) among white-tailed deer by Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 1995;32:368–74.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lockhart JM, Davidson WR, Dawson JE, Stallknecht DE, Howerth EW. Isolation of Ehrlichia chaffeensis from wild white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) confirms their role as natural reservoir hosts. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1681–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lockhart JM, Davidson WR, Dawson JE, Stallknecht DE, Little SE. Natural history of Ehrlichia chaffeensis in the Piedmont physiographic province of Georgia. J Parasitol. 1997;83:887–94. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lockhart JM, Davidson WR, Dawson JE, Stallknecht DE. Temporal association of Amblyomma americanum with the presence of Ehrlichia chaffeensis reactive antibodies in white-tailed deer. J Wildl Dis. 1995;31:119–24.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Magnarelli LA, Anderson AF, Stafford KC, Dumler JS. Antibodies to multiple tick-borne pathogens of babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, and Lyme borreliosis in white-footed mice. J Wildl Dis. 1997;33:466–73.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Davidson WR, Lockhart JM, Stallknecht DE, Howerth EW. Susceptibility of red and gray foxes to infection by Ehrlichia chaffeensis. J Wildl Dis. 1999;35:696–702.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Telford SR, Dawson JE. Persistent infection of C3H/HeJ mice by Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Vet Microbiol. 1996;52:103–12. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lockhart JM, Davidson WR, Stallknecht DR, Dawson JE. Lack of seroreactivity to Ehrlichia chaffeensis among rodent populations. J Wildl Dis. 1998;34:392–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dawson JE, Ewing SA. Susceptibility of dogs to infection with Ehrlichia chaffeensis, causative agent of human ehrlichiosis. Am J Vet Res. 1992;53:1322–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dawson JE, Biggie KL, Warner CK, Cookson K, Jenkens S, Levine JF, Polymerase chain reaction evidence of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, an etiologic agent of human ehrlichiosis, in dogs from southeast Virginia. Am J Vet Res. 1996;57:1175–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Murphy GL, Ewing SA, Whitworth LC, Fox JC, Kocan AA. A molecular and serologic survey of Ehrlichia canis, E. chaffeensis, and E. ewingii in dogs and ticks from Oklahoma. Vet Parasitol. 1998;79:325–39. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hair JA, Bowman JL. Behavioral ecology of Amblyomma americanum (L.). In: Sauer J, Hair JA, editors. Morphology, physiology, and behavioral biology of ticks. New York: Ellis Horwood Limited;1986. p. 406-27.

- Cooley RA, Kohls GM. The genus Amblyomma (Ixodidae) in the United States. J Parasitol. 1944;30:77–111. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Dawson JE, Warner CK, Baker V, Ewing SA, Stallknecht DE, Davidson WR, Ehrlichia-like 16S rDNA from wild white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). J Parasitol. 1996;82:52–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Anderson BE, Sumner JW, Dawson JE, Tzianabos T, Green CR, Olson JG, Detection of the etiologic agent of human ehrlichiosis by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:775–80.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dawson JE, Stallknecht DE, Howerth EW, Warner C, Biggie K, Davidson WR, . Susceptibility of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) to infection with Ehrlichia chaffeensis, the etiologic agent of human ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2725–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wilton SD, Lim L, Dye D, Laing N. Bandstab: a PCR-based alternative to cloning PCR products. Biotechniques. 1997;22:642–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kocan AA, Breshears M, Cummings C, Panciera RJ, Ewing SA, Barker RW. Naturally occurring hepatozoonosis in coyotes from Oklahoma. J Wildl Dis. 1999;35:86–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Baker RH. Origin, classification, and distribution. In: Halls L, editor. White-tailed deer. ecology and management. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books;1984. p. 1-18.

- Nowak RM. Walker's mammals of the world (5th ed). Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press;1991. vol. 2. p. 1068-70.

- Patrick CD, Hair JA. White-tailed deer utilization of three different habitats and its influence on lone star tick populations. J Parasitol. 1978;64:1100–6. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Bloemer SR, Zimmerman RH. Ixodid ticks on the coyote and gray fox at Land-Between-the-Lakes, Kentucky-Tennessee, and implications for tick dispersal. J Med Entomol. 1988;25:5–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Morchonton RL, Hirth DH. Behavior. In: Halls L, editor. White-tailed deer: ecology and management. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books;1984. p. 129-68.

- Ewing SA, Buckner RG, Stringer BG. The coyote, a potential host for Babesia canis and Ehrlichia sp. J Parasitol. 1964;50:704. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Buller RS, Arens M, Hmiel SP, Paddock CD, Sumner JW, Rikihisa Y, Ehrlichia ewingii, a newly recognized agent of human ehrlichiosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:148–55. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Anziani OS, Ewing SA, Barker RW. Experimental transmission of a granulocytic form of the Tribe Ehrlichieae by Dermacentor variabilis and Amblyomma americanum to dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1990;51:929–31.PubMedGoogle Scholar