Volume 8, Number 12—December 2002

Research

Meteorologic Influences on Plasmodium falciparum Malaria in the Highland Tea Estates of Kericho, Western Kenya

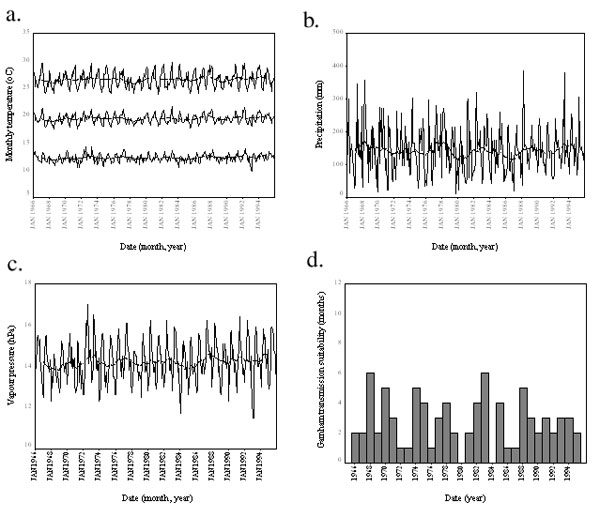

Figure 2

Figure 2. Climate and malaria suitability data for the Kericho area from the global gridded climatology data, including meteorologic and malaria suitability time series. Minimum (bottom), mean (middle) and maximum (top) monthly temperature (a) total monthly precipitation (b) and mean vapor pressure (c) are all plotted with a 25-point (month) moving average (bold) to show the overall movement in the data. The number of months per year suitable for malaria transmission (d) are also plotted. Suitability was determined if rainfall exceeded 152 mm and temperature exceeded 15°C in any month (1,4). The significance of these movements is presented in Table.

References

- Garnham PCC. Malaria epidemics at exceptionally high altitudes in Kenya. BMJ. 1945;11:45–7. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Strangeways-Dixon D. Paludrine (proguanil) as a malarial prophylactic amongst African labour in Kenya. East Afr Med J. 1950;27:127–30.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Malakooti MA, Biomndo K, Shanks GD. Reemergence of epidemic malaria in the highlands of western Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:671–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Garnham PCC. The incidence of malaria at high altitudes. J Natl Malar Soc. 1948;7:275–84.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lindblade KA, Walker ED, Onapa AW, Katungu J, Wilson ML. Land use change alters malaria transmission parameters by modifying temperature in a highland area of Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2000;5:263–74. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Van der Stuyft P, Manirankunda L, Delacollette C. L'approche de risque dans le diagnostic du paludisme-maladie en regions d'altitude. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1993;73:81–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bashford G, Richens J. Travel to the coast by highlanders and its implications for malaria control. P N G Med J. 1992;35:306–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lindblade KA, Walker ED, Onapa AW, Katungu J, Wilson ML. Highland malaria in Uganda: prospective analysis of an epidemic associated with El Niño. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:480–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pitt S, Pearcy BE, Stevens RH, Sharipov A, Satarov K, Banatvala N. War in Tajikistan and re-emergence of Plasmodium falciparum. Lancet. 1998;352:1279. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mouchet J, Manguin S, Sircoulon J, Laventure S, Faye O, Onapa AW, Evolution of malaria in Africa for the past 40 years: impact of climatic and human factors. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1998;14:121–30.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mouchet J. L'origine des épidémies de paludisme sur les Plateaux de Madagascar et les montagnes d'Afrique de L'est et du Sud. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1998;91:64–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Warsame M, Wernsdorfer WH, Huldt G, Björkman A. An epidemic of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Balcad, Somalia, and its causation. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:142–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Trape JF. Impact of chloroquine resistance on malaria mortality. Comptes Rendus de l'Academie des Sciences, Paris. 1998;321:689–97.

- Trape JF. The public health impact of chloroquine resistance in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:12–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bødker R, Kisinza W, Malima R, Msangeni H, Lindsay S. Resurgence of malaria in the Usambara mountains, Tanzania, an epidemic of drug-resistant parasites. Glob Change Hum Health. 2000;1:134–53. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Etchegorry MG, Matthys F, Galinski M, White NJ, Nosten F. Malaria epidemic in Burundi. Lancet. 2001;357:1046–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brown V, Issak MA, Rossi M, Barboza P, Paugam A. Epidemic of malaria in north-eastern Kenya. Lancet. 1998;352:1356–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- van der Hoek W, Konradsen F, Perera D, Amerasinghe PH, Amerasinghe FP. Correlation between rainfall and malaria in the dry zone of Sri Lanka. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91:945–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Loevinsohn ME. Climatic warming and increased malaria incidence in Rwanda. Lancet. 1994;343:714–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bouma MJ, Dye C, Van der Kaay HJ. Falciparum malaria and climate change in the northwest Frontier province of Pakistan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:131–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lindsay SW, Birley MH. Climate change and malaria transmission. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1996;90:573–88.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lindsay SW, Martens WJM. Malaria in the African highlands: past, present and future. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76:33–45.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- McMichael AJ, Haines A, Sloof R, Kovats S. Climate change and human health. Geneva:World Health Organization; 1996.

- Martens P, Kovats RS, Nijhof S, de Vries P, Livermore MTJ, Bradley DJ, Climate change and future populations at risk of malaria. Glob Environ Change. 1999;9:89–107. DOIGoogle Scholar

- National Research Council. Under the weather: climate, ecosystems, and infectious disease. Washington: The Council; 2001.

- Hay SI, Cox J, Rogers DJ, Randolph SE, Stern DI, Shanks GD, Climate change and the resurgence of malaria in the East African highlands. Nature. 2002;415:905–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- 2Hay SI, Cox J, Rogers DJ, Randolph SE, Stern DI, Shanks GD, et al. East African highland malaria resurgence independent of climate change. Directions in Science 2002;1:82–5.

- Hay SI, Rogers DJ, Randolph SE, Stern DI, Cox J, Shanks GD, Hot topic or hot air? Climate change and malaria resurgence in African highlands. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18. In press.

- Hay SI, Noor AM, Simba M, Busolo M, Guyatt HL, Ochola SA, The clinical epidemiology of malaria in the highlands of Western Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:543–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hay SI, Simba M, Busolo M, Noor AM, Guyatt HL, Ochola SA, Defining and detecting malaria epidemics in the highlands of western Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:555–62.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- 3Hay SI, Myers MF, Burke DS, Vaughn DW, Endy T, Ananda N, et al. Etiology of interepidemic periods of mosquito-borne disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97:9335–9.

- Shanks GD, Biomndo K, Hay SI, Snow RW. Changing patterns of clinical malaria since 1965 among a tea estate population located in the Kenyan highlands. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:253–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- New M, Hulme M, Jones P. Representing twentieth-century space-time climate variability. Part I: development of a 1961-90 mean monthly terrestrial climatology. J Climatol. 1999;12:829–57. DOIGoogle Scholar

- New M, Hulme M, Jones P. Representing twentieth-century space-time climate variability. Part II: development of 1901-1996 monthly grids of terrestrial surface climate. J Climatol. 2000;13:2217–38. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Granger CWJ, Newbold P. Spurious regressions in econometrics. J Econom. 1974;2:111–20. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Stern DI, Kaufmann RK. Detecting a global warming signal in hemispheric temperature series: a structural time series analysis. Clim Change. 2000;47:411–38. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Dickey DA, Fuller WA. Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. J Am Stat Assoc. 1979;74:427–31. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Dickey DA, Fuller WA. Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive processes. Econometrica. 1981;49:1057–72. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Box G, Pierce D. Distribution of autocorrelations in autoregressive moving average time series models. J Am Stat Assoc. 1970;65:1509–26. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Matola YG, White GB, Magayuka SA. The changed pattern of malaria endemicity and transmission at Amani in the eastern Usambara Mountains, north-eastern Tanzania. J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;90:127–34.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Marimbu J, Ndayiragije A, Le Bras M, Chaperon J. Environment and malaria in Burundi: apropos of a malaria epidemic in a non-endemic mountainous region. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1993;86:399–401.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Some E. Effects and control of highland malaria epidemic in Uasin Gishu District, Kenya. East Afr Med J. 1994;71:2–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tulu AN. Determinants of malaria transmission in the highlands of Ethiopia: the impact of global warming on mortality and morbidity ascribed to malaria. In: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. London:University of London; 1996.

- Kilian AHD, Langi P, Talisuna A, Kabagambe G. Rainfall pattern, El Niño and malaria in Uganda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:22–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Epstein PR, Diaz HF, Elias S, Grabherr G, Graham NE, Martens WJM, Biological and physical signs of climate change: focus on mosquito-borne diseases. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 1998;79:409–17. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Martens P. How will climate change affect human health? Am Sci. 1999;87:534–41.

- Patz JA, Lindsay SW. New challenges, new tools: the impact of climate change on infectious diseases. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:445–51. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bonora S, De Rosa FG, Boffito M, Di Perri G, Rossati A. Rising temperature and the malaria epidemic in Burundi. Trends Parasitol. 2001;17:572–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McCarthy JJ, Canziani OF, Leary NA, Dokken DJ, White KS. Climate change 2001: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability—contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 2001.

- Patz JA, Reisen WK. Immunology, climate change and vector-borne diseases. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:171–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reiter P. Global-warming and vector-borne disease in temperate regions and at high altitude. Lancet. 1998;351:839. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reiter P. Climate change and mosquito-borne disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:141–61. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rogers DJ, Randolph SE. The global spread of malaria in a future, warmer world. Science. 2000;289:1763–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rogers DJ, Randolph SE, Snow RW, Hay SI. Satellite imagery in the study and forecast of malaria. Nature. 2002;415:710–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Page created: July 19, 2010

Page updated: July 19, 2010

Page reviewed: July 19, 2010

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.