Volume 8, Number 9—September 2002

Historical Review

Biological Warfare at the 1346 Siege of Caffa

Figure 2

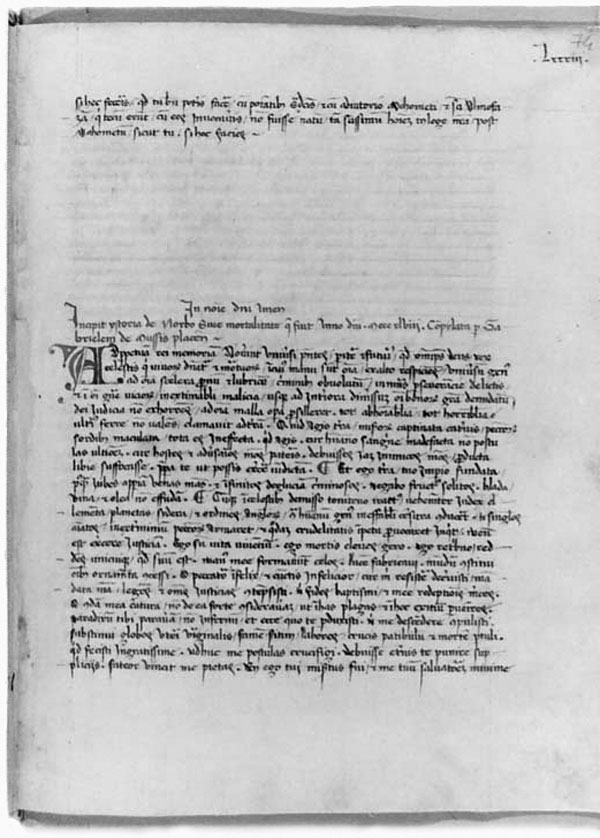

Figure 2. The first page of the narrative of Gabriele de’ Mussi. At the top of the page are the last few lines of the preceding narrative; de’ Mussi’s begins in the middle of the page. The first three lines, and the large “A” are in red ink, as are two other letters and miscellaneous pen-strokes; otherwise it is in black ink. Manuscript R 262, fos 74r; reproduced with the permission of the Library of the University of Wroclaw, Poland.

1Technically trebuchets, not catapults. Catapults hurl objects by the release of tension on twisted cordage; they are not capable of hurling loads over a few dozen kilograms. Trebuchets are counter-weight-driven hurling machines, very effective for throwing ammunition weighing a hundred kilos or more (22).

2Medieval society lacked a coherent theory of disease causation. Three notions coexisted in a somewhat contradictory mixture: 1) disease was a divine punishment for individual or collective transgression; 2) disease was the result of "miasma," or the stench of decay; and 3) disease was the result of person-to-person contagion (23).